UCSD physicists find that last, long-lost lunar retroreflector

San Diego, CA--A team of physicists led by a professor at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) has pinpointed the location of a long-lost optical retroreflector left on the lunar surface by the Soviet Union nearly 40 years ago that many scientists had unsuccessfully searched for and never expected would be found.

The French-built laser reflector was sent aboard the unmanned Luna 17 mission, which landed on the moon on November 17, 1970, releasing a robotic rover that roamed the lunar surface and carried the missing laser reflector. The Soviet lander and its rover, Lunokhod 1, were last heard from on September 14, 1971.

"No one had seen the reflector since 1971," said Tom Murphy, an associate professor of physics at UCSD. He heads a team of scientists engaged in a long-term effort to look for deviations of Einstein's theory of general relativity by measuring the shape of the lunar orbit to within an accuracy of 1 mm using laser ranging. They rely on the retroreflectors left on the moon by Apollo astronauts for an adequate pulse return.

Lunar orientation, tidal distortion

"We routinely use the three hardy reflectors placed on the moon by the Apollo 11, 14 and 15 missions," said Murphy, "and occasionally the Soviet-landed Lunokhod 2 reflector--though it does not work well enough to use when illuminated by sunlight. But we yearned to find Lunokhod 1."

Three reflectors are required to lock down the orientation of the moon. A fourth adds information about tidal distortion of the moon, and a fifth enhances that information.

"Lunokhod 1, by virtue of its location, would provide the best leverage for understanding the liquid lunar core, and for producing an accurate estimate of the position of the center of the moon--which is of paramount importance in mapping out the orbit and putting Einstein's gravity to a test," said Murphy.

Sighted by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

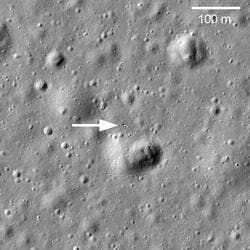

Murphy said his team had occasionally looked for the Lunokhod 1 reflector over the last two years, but faced tall odds against finding it until recently. The breakthrough came last month when the high-resolution camera on NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, or LRO, obtained images of the landing site. The camera team, led by Mark Robinson at Arizona State University, identified the rover as a sunlit speck on the image--miles from where Murphy and his team had been searching. But until now, the existence of the reflector or its precise location was unknown.

On April 22, his team sent pulses of laser light from the 3.5 m telescope at the Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico, zeroing in on the target coordinates provided by the LRO images. Murphy, together with Russet McMillan of the Apache Point Observatory in Sunspot, NM and UCSD physics graduate student Eric Michelsen, found the Lunokhod 1 reflector and pinpointed its distance from earth to within 10 mm. They then made a second observation less than 30 minutes later that allowed the team to triangulate the reflector's latitude and longitude on the moon to within 10 m. In the coming months, he estimates it will be possible to establish the reflector's coordinates to better than 10 mm precision.

An excellent 2000-photon return

"We quickly verified the signal to be real and found it to be surprisingly bright: at least five times brighter than the other Soviet reflector, on the Lunokhod 2 rover, to which we routinely send laser pulses," Murphy said. "The best signal we've seen from Lunokhod 2 in several years of effort is 750 return photons, but we got about 2000 photons from Lunokhod 1 on our first try. It's got a lot to say after almost 40 years of silence."

Murphy's project, dubbed APOLLO (the Apache Point Observatory Lunar Laser-ranging Operation), is supported by the National Science Foundation and NASA, and includes scientists at the University of Washington, Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Humboldt State University and the Apache Point Observatory.

(Material adapted from a UCSD release by Kim McDonald.)

John Wallace | Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.