Tübingen, Germany--Researchers at the University of Tübingen Eye Hospital have developed a retinal implant that has allowed three blind people to see shapes and objects within days of the implant being installed.

One blind person was even able to identify and find objects placed on a table in front of him, as well as walking around a room independently and approaching people, reading a clock face and differentiating seven shades of grey. The photodiode array has 38 x 40 pixels. It was developed by the company Retinal Implant AG together with the Institute for Ophthalmic Research at the University of Tübingen, and represents an unprecedented advance in electronic visual prostheses that could eventually revolutionise the lives of up 200,000 people worldwide who suffer from blindness as a result of retinitis pigmentosa, a degenerative eye disease.

"The results of this pilot study provide strong evidence that the visual functions of patients blinded by a hereditary retinal dystrophy can, in principle, be restored to a degree sufficient for use in daily life," said Eberhart Zrenner, founding director of Retinal Implant AG.

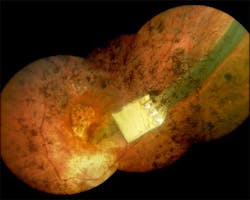

The device--known as a subretinal implant--sits underneath the retina, directly replacing light receptors lost in retinal degeneration. As such, it uses the eyes' natural image processing capabilities beyond the light-detection stage to produce a visual perception in the patient that is stable and follows their eye movements. Other types of retinal implants--known as epiretinal implants--sit outside the retina; because they bypass the intact light-sensitive structures in the eyes, they require the user to wear an external camera and processor unit.

Subscribe now to Laser Focus World magazine; it’s free!

John Wallace | Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.