From the Max Planck Institute: glass that repels water and oil

Mainz, Germany--Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research and the Technical University Darmstadt have created a transparent superamphiphobic coating for glass that is also made of glass; both oil and water both roll off this coating, leaving no residue. The material owes this property to its nanostructure. The coating could be used for eyeglasses, car windscreens, and the glass facades of skyscrapers. It could also prevent residues of blood or contaminated liquids on medical equipment.

The coating essentially consists only of silica. The researchers coated this with a fluorinated silicon compound, which already makes a glass surface water and oil repellent. However, it is the structure of the coating that makes the glass water and oil repellent. The structure is a labyrinth of completely unordered pores made made up of nanospheres.

“The rounded surfaces cannot be wet even by low-viscosity oils, although this would be energetically most favorable,” says Doris Vollmer, who heads a research group at the Max Planck Institute for Polymer Research. This is because the liquids that wet even fluorinated surfaces would have to be pressed over these spheres (which measure around 60 nm in diameter) to form a film on the surface; this requires too much energy.

The soot from a candle flame, from which the researchers made a template, served as the model for the porous structure of the spheres. The researchers held a glass slide in a flame so that the soot particles, which measure around 40 nm in diameter, formed a spongelike structure on the glass. The layer was then coated by vapor-depositing a volatile organic silicon compound and ammonia onto the soot deposit. When the material was heated, the soot decomposed. Finally, a fluorinated silicon compound was vapor-deposited onto the hollow silica structure.

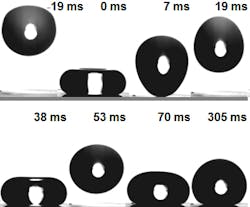

They then attempted to wet this coating with different liquids. However, they didn’t succeed, even when they let hexadecane drip from a great height onto it; in a nonstick frying pan, hexadecane spreads out like water in a washbasin. “Initially, a drop of the oil penetrated into the sponge-like structure, but then bounced back like a rubber ball,” says Vollmer. Although a portion of the liquid remained in the pores and wet the material, when most of the drop returned to the surface at a slower speed after bouncing up, it drew the small amount of the hexane that had remained out of the glass pores again. Finally, the reunited drop remained as a sphere on the surface. The researchers in Mainz tested the superamphiphobic layer with a total of seven liquids and found that none was sucked up by the glass sponge.

The layer only loses its self-cleaning properties when the layer becomes thinner than one micron. And this is precisely what would happen quite soon in practice, even if a self-cleaning sponge structure several microns thick was used to coat the lenses of eyeglasses or a windowpane. When the researchers let sand trickle onto the delicate glass structure, the coating was worn away quite quickly. “In a next step, we would therefore like to develop a layer that is superamphiphobic with better mechanical stability,” says Vollmer.

John Wallace | Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.