'Temporal cloaking' could bring more secure optical communications

West Lafayette, IN--Researchers at Purdue University have demonstrated a method for "temporal cloaking" of optical communications. The work is a time-based analogue of spatial cloaking, such as so-called "invisibility cloaking." Findings were detailed in a research paper appearing in the advance online publication of the journal Nature.

Researchers at Cornell University (Ithaca, NY) invented temporal cloaking in 2011, but their approach cloaked only a small fraction (1 x 10-6) of the time available for optically sending data. Now, the Purdue researchers have increased that to about 46%, potentially making the concept practical for commercial applications such as improving security for telecommunications.

"More work has to be done before this approach finds practical application, but it does use technology that could integrate smoothly into the existing telecommunications infrastructure," said Joseph Lukens, a student in Purdue University's electrical engineering graduate program working with his professor, Andrew Weiner.

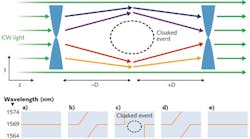

While the previous research in temporal cloaking required the use of a picosecond laser, the Purdue researchers achieved the feat using off-the-shelf equipment commonly found in commercial optical communications. The technique works by manipulating the phase of light pulses; the data in regions of destructive interference would be cloaked. In temporal cloaking, two phase modulators are used to first create the holes and two more to cover them up, making it look as though nothing was done to the signal.

"It's a potentially higher level of security because it doesn't even look like you are communicating," Lukens said. "Eavesdroppers won't realize the signal is cloaked because it looks like no signal is being sent."

John Wallace | Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.