Variance spectroscopy method from Rice University advances nanoparticle analysis

Rice University (Houston, TX) scientists have developed a powerful method to analyze carbon nanotubes in solution called variance spectroscopy that zooms in on small regions in dilute nanotube solutions to take quick spectral snapshots. By analyzing the composition of nanotubes in each snapshot and comparing the similarities and differences over a few thousand snapshots, the researchers gain new information about the types, numbers and properties of the nanoparticles in the solution.

RELATED ARTICLE: Accessing molecular structure with Raman spectroscopy

The process, detailed in an open-access paper in the ACS Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, was developed by Rice chemist Bruce Weisman, a pioneer in the field of spectroscopy who led the discovery and interpretation of near-infrared fluorescence from semiconducting carbon nanotubes.

Because there is no practical way yet to grow just one type of carbon nanotube, they often need to be sorted by physical or chemical means. Weisman said variance spectroscopy could help characterize nanotube samples in the ongoing drive to sort and separate specific types for electronic and optical applications.

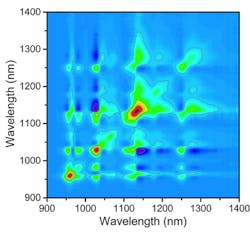

The Weisman lab tested its custom rig on dispersed samples of single-wall carbon nanotubes grown at Rice. The researchers captured fluorescence spectra from a few thousand distinct small regions. Statistical variations among these spectra revealed the numbers of nanotubes of different types and how strongly each type emits light. Further data analysis gave “dissected” spectra of each type, free of interference from others in the mixed sample.

"As we focus our attention on smaller and smaller volumes of the sample, the averaged-out, uniform behavior you see on the macroscopic scale starts to break down, and we see effects from the particulate nature of matter," he said. "At that point, there are random fluctuations in the numbers of particles within the observed volume. What we're doing is analyzing the resulting random fluctuations in spectra to learn about how many particles of each type are present and whether they're aggregated with each other.

"An analogy might be looking at fans in a football stadium wearing their teams' colors," Weisman said. "If you stand way back and look at the whole crowd, all you can figure out is the overall ratio of Rice fans to Texas fans. But if you zoom in and analyze row by row, you're going to see clusters of Rice fans and clusters of Texas fans and learn how each group aggregates together. That gives you extra insights about the crowd that you could never get from the big view."

Weisman said the technique also helps address nanotubes’ annoying tendency to clump together. "When you're trying to use a separation method to sort them out, you can't do it effectively if they’re stuck together," Weisman said. "If you want type A and they're stuck to type B, then you’re wasting your separation effort. But variance spectroscopy provides a very sensitive way to tell whether particles of different types are actually traveling together."

Weisman expects variance spectroscopy can be extended to analyze many nanoscale materials, like gold nanoparticles and quantum dots, using different spectroscopic probes. “When you make nanomaterials, there is generally some variation in particle sizes that gives a corresponding variation in the spectral properties,” he said. “Our variance method can be used with such systems to take a look inside.”

The National Science Foundation and the Welch Foundation supported the research.

SOURCE: Rice University; http://news.rice.edu/2015/09/28/smaller-is-better-for-nanotube-analysis/

About the Author

Gail Overton

Senior Editor (2004-2020)

Gail has more than 30 years of engineering, marketing, product management, and editorial experience in the photonics and optical communications industry. Before joining the staff at Laser Focus World in 2004, she held many product management and product marketing roles in the fiber-optics industry, most notably at Hughes (El Segundo, CA), GTE Labs (Waltham, MA), Corning (Corning, NY), Photon Kinetics (Beaverton, OR), and Newport Corporation (Irvine, CA). During her marketing career, Gail published articles in WDM Solutions and Sensors magazine and traveled internationally to conduct product and sales training. Gail received her BS degree in physics, with an emphasis in optics, from San Diego State University in San Diego, CA in May 1986.