MALDI-TOF brings greater sensitivity to protein research

No one disputes that the mapping of the human genome was a historic accomplishment. But it could one day pale in comparison to understanding the proteins that support our molecular structure. While there are 30,000 to 40,000 unique genes in the human body, scientists believe these genes represent hundreds of thousands of different proteins, presenting an even more complex analytical challenge with monumental implications for disease detection and treatment.1

In its broadest sense, the goal of proteomics is to understand protein expression in response to conditions such as infection, disease, and other factors. Complex biological samples such as tissues, tumors, serum, or cells contain hundreds to thousands of proteins in a wide range of concentrations. By identifying, analyzing, and understanding proteins and protein pathways, researchers should be able to earmark critical proteins involved in the onset of various diseases, and diagnose and treat these diseases at their most basic level. In turn, this same information will help drug developers formulate new pharmaceuticals that can better target and treat the conditions for which they are intended. Multimedia Research Group (Sunnyvale, CA) estimates that the market for proteomics instrumentation will grow from $565 million in 2001 to more than $3 billion in 2006.

"Protein analysis, detection, and characterization have been around for decades, but the focus has shifted to better understanding the relevance of proteins as they relate to disease and disease states," said Sandra Rasmussen, proteomics business leader at PerkinElmer LifeSciences (Boston, MA). "One of the difficulties in doing protein analyses is that the proteome (the total protein complement of an organism) of an individual is very dynamic. So the challenge in proteomics is that any given time slice is just that—a picture of that time slice. There are hundreds, thousands, even millions of other time slices that need to be looked at and corroborated, which begs the need for studying more and more and more samples."

This need has created a great opportunity for matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS). Prior to the introduction of MALDI in the late 1980s, mass spectrometers had been used in biology for years, but were limited to the study of small molecules. With the introduction of fast atom bombardment ionization—a matrix-based technique that uses atomic collisions rather than lasers to "smash" larger molecules and ionize the sample—mass spectrometers began to be used for protein research.2 These systems were still limited in terms of their mass range, however, and the only way to identify a protein was to isolate it on a two-dimensional gel and then sequence it, a process that took days and sometimes weeks and overlooked certain classes of proteins.3

But the mapping of the human genome prompted a surge of interest in extending the analytical capabilities of MS. This interest in turn led to the development of ion traps and time-of flight (TOF) mass spectrometers that utilize electrospray, MALDI, or some other ionization method to better ionize and separate large molecules prior to their analysis. MALDI has become one of the most common ionization methods because it causes little to no fragmentation of the molecule during ionization and desorption. The sample to be analyzed is mixed with a laser-energy-absorbing photoactive compound such as alpha-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid and the mixture is then irradiated with a pulsed laser—typically a 337-nm nitrogen laser (see Fig. 1). The matrix compound absorbs the light and uses the energy to eject and ionize the embedded protein molecules.

"The beauty of MALDI is that the sample is static," said Dave Hicks, director of marketing for proteomics at Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). "You mix the sample with the matrix and then it is frozen in time in a solid state so you can analyze and reanalyze as needed without having to rerun the whole sample."

MALDI-TOF maps more

Since its introduction MALDI-MS has had its biggest impact in protein research. When MALDI ionization sources are incorporated into TOF mass spectrometers, they provide a range of analytical features—speed, sensitivity, accuracy, resolution, and mass range—that are critical to teasing apart the intricacies of proteomes.

Current proteomics research falls into three broad segments: protein discovery and expression (including peptide sequencing), protein-function analysis, and protein-structure analysis. Using a MALDI-TOF MS, the molecular weight of the intact protein—one of the most useful attributes in protein identification—can be accurately determined. While MALDI-TOF spectrometers have been commercially available for the past decade, the desire to gain more information from larger samples with greater accuracy, sensitivity, and resolution is pushing mass spectrometer developers to refine and even automate MALDI-TOF technologies and techniques.

One advance being pursued by several companies and researchers is atmospheric-pressure (AP) MALDI as an alternative to traditional vacuum-based MALDI-MS systems. Proponents say that, unlike vacuum MALDI-TOF configurations, mass resolution using AP MALDI would not be plagued by the initial kinetic energy and spatial distribution of the ions.4 Samples could thus be presented in volatile solvents, on nonconducting glass slides, or as whole cells or tissues.

Citing these and other advantages, Agilent (Palo Alto, CA) and MassTech (Burtonsville, MD) have introduced the AP-MALDI. According to John Michnowicz, head of the AP-MALDI proteomics effort at Agilent, the AP-MALDI is more reliable and less costly, selling for "a fraction" of the nearly $500,000 price tag of most quadrupole-TOF or TOF-TOF mass spectrometers but offering many of the same capabilities.

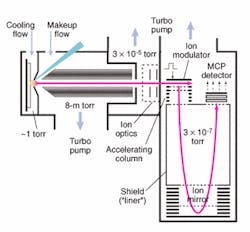

Another advance involves decoupling the MALDI source from the TOF to increase mass accuracy. Working in conjunction with MDS Sciex (Concord, Ontario, Canada) and using technology licensed from the University of Manitoba, PerkinElmer has developed a MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer, the prOTOF 2000, which uses an orthogonal design and collisional cooling to achieve higher rates of successful protein identification (see Fig. 2). In the prOTOF 2000, the MALDI source is decoupled from the TOF, which the company says eliminates the discrepancies typically encountered in conventional linear or axial MALDI-TOF designs.

The prOTOF 2000 also incorporates new collisional cooling technology intended to improve upon the more conventional delayed extraction approach to protein identification. Rather than using individual laser pulses to create individual mass spectrums and then adding up all those spectrums to create the protein fingerprint, the prOTOF 2000 continuously pulses the laser from 50 to 100 Hz (two to 10 times faster than existing systems), establishes a steady-state ion beam, and records multiple spectra off of that continuous ion beam. According to Eric Denoyer, proteomics technology leader for PerkinElmer, collisional cooling is important because it enables extremely sharp spectra.

"We have put a huge effort into the interface between the laser and mass spectrometer and into how you actually couple the laser ionization to the spectrometer," he said. "Without collisional cooling, the laser ionization would produce very wide mass peak and poor resolution."

Doubling up and trimming down

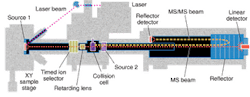

Applied Biosystems has also partnered with MDS Sciex to leverage Applied Bio's extensive background in MALDI-TOF technologies into the next generation of mass spectrometers. As a result, Applied Bio has become a leader in tandem mass spectrometry—also known as MS/MS or TOF-TOF—for protein identification. These systems use a two-stage approach to peptide analysis, yielding more precise identification of specific peptides and post-translational peptide modifications.

According to Applied Bio, a common challenge in the identification of proteins from databases is the analysis of peptides with matching molecular-weight readings after one round of MS analysis. By applying a second stage of analysis (MS/MS), these peptides can be broken apart into smaller pieces, making it easier to identify specific peptides and differences in peptides.

Applied Bio offers a range of MALDI MSs, some of which allow customers to perform MALDI ionization and MS/MS on the same platform, reducing manual handling and increasing the information obtained with MALDI ionization. The company's latest offering is the 4700 Proteomics Analyzer, introduced in January 2002 (see Fig. 3). This system combines MALDI with proprietary TOF/TOF optics to enable throughput of up to 1000 samples per hour. The tandem MS capability of the analyzer allows researchers to select a specific peptide ion in the first TOF MS, fragment it by collision-induced dissociation, and obtain peptide-sequence data in the second MS.

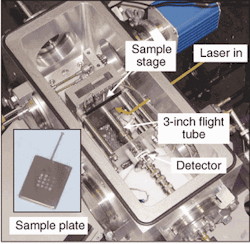

Other groups are working to reduce the size of these instruments and make them more practical for applications outside the lab. Researchers at the Middle Atlantic Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (Baltimore, MD) have spent the last several years developing miniature TOF mass spectrometers for use in environmental, bioagent detection, and diagnostic applications. Under the direction of Robert Cotter, professor of pharmacology and molecular sciences at Johns Hopkins, the lab has developed a 3-in. mass spectrometer that can achieve mass resolution of one part in1200 and mass range of more than 66 kdaltons (see Fig. 4). Cotter believes that these "mini MSs" could eventually incorporate some of the data collection and analysis work currently being done with high-end protein analyzers into compact MSs suitable for use in clinical environments.

"Once the biomarkers for disease are identified by the larger, more expensive, high-precision instruments, they could be recognized in a smaller diagnostic version," he said.

REFERENCES

- Applied Biosystems white paper, Proteomics Technology at a New Level, see www.appliedbiosystems.com.

- J. M. Perkel, The Scientist 15(16) 31 (Aug. 20, 2001).

- J. F. Wilson, The Scientist 15(7) 12 (April 2, 2001).

- S. C. Moyer and R. J. Cotter, Analytical Chemistry, 74(18) 469A (Sept. 1, 2002).

A mass-spectrometry primer

Mass spectrometry is the characterization of matter through the separation and detection of gas-phase ions according to their mass as a function of the number of charge states (mass-to-charge ratio, or m/z) of these ions.1 In modern mass-spectrometry instrumentation, molecules are ionized in the ion source to form molecular ions, some of which fragment. The ions are accelerated into a mass analyzer, passing through one at a time to reach the detector. When the ions strike the detector, they are converted into an electrical signal that, in turn, is converted into a digital response.

There are five different types of mass spectrometers: magnetic sector/double focusing, transmission quadrupole, quadrupole ion trap, time of flight (TOF), and Fourier transform ion-cyclotron resonance. In TOF mass spectrometers, ions are accelerated from the ion-source region into a field-free drift region, where they move toward the instrument's detector with a velocity that is determined by their m/z value. Ions of lower m/z values will have higher velocities than those of higher m/z values and will reach the detector first. Unlike other mass spectrometers, with TOF mass spectrometers there is no limitation to the maximum m/z value that can be analyzed.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization (MALDI) TOF mass spectrometers use pulses of laser light to desorb the analyte from a solid phase directly to an ionized gas state. Prior to the introduction of MALDI, pulsed lasers had been used to ionize proteins, but the technique was limited due to protein light absorption.

REFERENCE

- O. D. Sparkman, in Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry, R. A. Meyers, Ed., 11501 (Wiley: Chichester, England; October 2000).

Dispute surrounds Nobel MALDI-MS prize

The importance of matrix-assisted laser desorption and ionization (MALDI) to biology, chemistry, and protein research was made clear when two pioneers in this field were awarded the 2002 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Toichi Tanaka, a researcher with Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan), and John Fenn of Virginia Commonwealth University (Richmond, VA) shared the 2002 Nobel Prize for Chemistry "for their development of soft-desorption-ionization methods for mass-spectrophotometric analyses of biological macromolecules."

In 1988, Tanaka designed a system in which freely hovering ions are generated from biomolecules in a solid or viscous sample, setting the stage for the application of mass spectrometry to large molecules. Fenn's contribution was electrospray ionization, another critical step in high-end protein analysis.

Controversy surrounded Tanaka and Fenn's award, however; some researchers claim that two German chemists, Michael Karas and Franz Hillenkamp, actually should have received the honor because of their contributions, which included demonstrating the use of an organic acid that would absorb in the near-ultraviolet—the method now most commonly used worldwide. It is generally acknowledged that their work was instrumental in paving the way for widespread adoption of MALDI techniques worldwide.