While developing holographic and other diffractive optics for use with optical tweezers, two researchers from Innsbruck Medical University (Innsbruck, Austria) came up with a theoretical model for a set of optics that could have wider practical application, both in the laboratory and in inexpensive mass-market devices. The optics, a pair of diffractive optical elements (DOEs) that combine to produce a moiré affect, can be rotated with respect to each other to vary their combined focal length.1

The researchers, Stefan Bernet and Monika Ritsch-Marte, discovered that the idea of combining two specially patterned DOEs and moving one of them to create a variable focal length was an old one.2 However, the version developed by Bernet and Ritsch-Marte has advantages that make it more suitable for practical use.

Unlike Fresnel zone plates, which are based solely on modulating the intensity of an incoming wavefront, DOE Fresnel lenses solely modulate the phase of a wavefront (returning to 0 after reaching 2∏) via phase structures resulting from either a spatially varying surface or index of refraction. They can be mass-produced; for example, Canon uses DOEs in some of its top-of-the-line camera lenses.3While Fresnel zone plates have low efficiency because they absorb some light and diffract some into undesired orders, and while holographic optics lose light into undesired orders, DOEs can approach 100% efficiency.

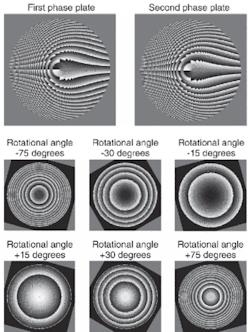

The first moiré DOE (MDOE) variable Fresnel lens developed by the Austrian researchers consisted of two DOEs with mirror image patterns; when overlaid with a 0° shift, they passed an unaltered wavefront. When one was rotated, they generated a positive optical power that varied with the rotation angle. However, they also produced an undesired effect: a pie-slice-shaped sector of the wavefront—with a slice angle equal to the rotation angle—generated a completely different optical power, greatly reducing the usefulness of the lens.

In response, Bernet and Ritsch-Marte modified the MDOE phase patterns such that a certain portion (an exponent) of the mathematical function describing the phase was rounded to the next highest integer as a function of the radius. The resulting phase pattern shows radial discontinuities; however, the moiré phase pattern produced by the MDOE contains no unwanted pie-shaped sector (see figure). The main disadvantage of the second DOE version is that, for increasing rotation angles, the phase pattern begins to look like two overlaid Fresnel lenses.

Spherical, axicon, helical

In one example, an MDOE with pixels 1 µm in size and a diameter of 10 mm, designed for use at a 500 µm wavelength, has a focal-length range variable between ±4 cm and ±∞ when rotated between an angle of ±90° (efficiency at 0° is 100%, and drops to 85% at ±90°). This sort of MDOE is not restricted to producing spherical wavefronts: a variable-power axicon was also designed, as well as a spiral-phase version with a variable helical phase.

“We are planning to create an experimental prototype,” says Bernet. “Unfortunately, although our MDOE might be quite inexpensive in mass production, the realization of a prototype is expensive because the fine phase pattern has to be produced by lithography (followed by different etching steps and so on) on a master element. Afterward, copies of it can be produced more easily by ‘stamping’ the master phase relief into a polymer.” One advantage of the design is that each MDOE is always made of two identical DOEs, with one merely flipped with respect to the other; thus, only one master has to be fabricated.

Bernet points to inexpensive mobile-phone cameras as an interesting market, although he is not sure whether the imaging quality of the MDOE would be sufficient. “Maybe other applications in which fixed-focus Fresnel lenses are already being used are more interesting,” he says. “For example, Fresnel lenses are sometimes used as front lenses in telecentric camera systems that require a large field of view, or they are used as cheap lenses in the viewfinders of cameras (not as the objective lens), or illumination systems (collimators) or projectors, which do not require precision optical performance.”

The Austrian researchers have applied for a patent on their idea and are in contact with a company that wants to finance a first prototype.

REFERENCES

- S. Bernet and M. Ritsch-Marte, Appl. Optics 47(21) 3722 (July 20, 2008).

- A.W. Lohmann, Appl. Optics 9, 1669 (1970).

- www.canon.com/technology/canon_tech/explanation/do_lens.html

John Wallace | Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.