EUROPEAN REPORT - Photonics drives growth in the EU

Viviane Reding, European commissioner for information society and media, recently said, “Photonics is driving innovation in Europe.” While it is a bold statement, it is clear that the role of photonics as a horizontal industry continues to grow and very few industries remain untouched by new developments in this sector.

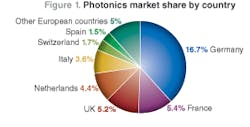

Recently published documents confirm that the European Union (EU) has a larger share of the worldwide production of photonics products than North America, at 19% versus 15% respectively, with Germany holding the largest market share (see Fig. 1). What’s more, these reports indicate that the EU has exceptionally strong market positions in many key photonics domains including production technology, photovoltaic energy production, and lighting.1, 2

Photonics is now acknowledged in the European-funded research program Framework Programme (FP) 7 as being among the essential drivers for Europe’s future economic growth. In recognition of the sector’s importance, Reding increased the budget available for photonics by 40% in the recent funding round, with the possibility of future increases. She also set up a special photonics unit in the European Commission. This initiative was recognized by the Optical Society of America, which named Commissioner Reding and Thierry Van der Pyl, head of the European Commission’s (EC) Photonics Unit, as its 2008 “Advocates of Optics”—the first time that the honor was awarded outside of the United States.

Framework Programmes are the EC’s primary funding instruments for research and technological development. FP6, which covered 2002-2006 with nearly €18 billion (US$28.19 billion), contributed to the Lisbon Strategy and gave rise to many groundbreaking programs in photonics. The Lisbon Strategy, or Agenda, is a strategic accord achieved in March 2000 when EU leaders agreed that ensuring a leadership position for future generations meant defining strategic economic priorities, notably in high-technology. Today, the EC, industrials and researchers recognize what they have accomplished, but they also admit that much remains to be done.

One of the most significant developments in recent years in European photonics was the establishment of Photonics21, an EC-supported initiative that formed a free-association structure uniting photonics professionals from academia and industry. Photonics21 (www.photonics21.org) has grown from a small handful of members into a multidisciplinary organization that will evolve to meet the needs of its members. OPERA2015 (www.opera2015.org), whose EC-supported mission was to provide a platform for facilitating interaction across the photonics sector, has created an impressive database of industrial and academic actors. This seemingly simple concept has had an important impact on innovation by making it significantly easier for photonics community members to find each other and work together.

Today, many FP6 programs are coming to a close and FP7 is beginning. FP7 will cover the period from 2007 through 2013 and boasts an impressive €55 billion (US$23.49 billion) in funding. How do those responsible for piloting the Programme’s ambitious projects plan to surmount the challenges ahead of them?

At the 2008 SPIE Photonics Europe meeting, Ronan Burgess, from the Photonics Unit at the European Commission Directorate General for Information Society and Media, spoke passionately about the group’s vision for the future of this sector in Europe. “The organization has been hugely successful in bringing together most of the significant players in the photonics field including researchers, educators, and industrials,” says Burgess. “One measure of its success is the growth of its membership from the initial 200 to now over 950, half of which are industrials” (see “Burgess sees a bright future”).

Facilitating collaboration in an ever growing Union

Although the focus of EC photonics policy is on fostering collaboration between industry and academia across Member States, two key challenges need to be addressed. First, an infrastructure must exist to enable all the different players on the photonics scene to act together. Second, the EU must face the challenge that it exists in a larger, highly competitive world.

The EC and the projects it has supported have not ignored either of these facts. For example, one of the most accessible EU photonics resources is OPERA2015, according to project coordinator Markus Wilkens. “When we started the project back in 2005, nobody could really tell how many companies or scientific research labs in Europe were active in photonics,” says Wilkens. “To date, we have collected information on more than 2000 companies and 700 research labs in Europe. This data is now accessible to anyone interested at www.opera2015.org”

The project continues under Photonics21. “OPERA2015 is, and always has been, a complementary activity to the ETP Photonics21, and we have always worked very closely together,” says Wilkens. “During the past three years, Photonics21 has become the central organization for photonics in Europe regarding the coordination of R&D strategy and industrial implementation. The top-down approach used in the Photonics21 economic impact study is complemented by the bottom-up approach OPERA2015 has chosen for compiling company and research-lab information. The upcoming integration of OPERA2015 into Photonics21 is a natural evolution that will yield one central information resource for photonics in Europe. As a matter of fact, the European Commission FP7 project Phorce21 will begin in May 2008 to support Photonics21 secretariat activities.”

Investment + infrastructure = innovation?

The EC has assembled a successful infrastructure for communication and cooperation. Networks of excellence have sprung forth in a variety of photonics domains and national organizations have evolved to meet the needs of their members. The European photonics market earned €49 billion (US$76.71 billion) in 2006 and yet there is still concern among people at every level that somewhere, somehow, it’s just not enough.

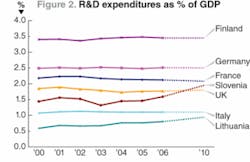

Even though no one seems to be able to put a finger on the exact cause of their worries, one of the recurring themes of discussion is invention versus innovation. As mentioned earlier, EU leaders made and reaffirmed strong commitments to sustainable development with the Lisbon Strategy in 2000 and 2005. One of those engagements was to reinvest 3% of GDP into R&D. 1% was to come from public sources, 2% from private industry. Currently, overall EU R&D investments account for 1.86% of GDP. If current trends continue, the EU will not meet its strategic goal (see Fig. 2).Although the EU strives to create equanimity among the citizens of Member Sates, is it fair or even realistic to place photonics in the realm of the “pan-European?” That’s not to say that it shouldn’t be accessible to any EU citizen who aspires to working in this intriguing field. But should we expect each Member State to make the same commitment even when their economies are structured differently?

Maybe not, says SPIE CEO Eugene Arthurs. “Looking at GERD (gross expenditures on R&D) in more detail inside the U.S. or inside Europe as a whole suggests to me that averages can mislead,” he says. “The U.S. sits around 2.5%, Japan above 3%, and so on, but within the U.S., states range from 8% down. Why should a state have a high GERD, a high expenditure on R&D for high technology, if its GDP is mainly derived from agricultural produce? Likewise for Europe. Trying to get all states to 3% may be much less effective than getting the technology-driven states to 5%.

“High GERD is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for an efficient national innovation infrastructure,” he adds. “It is a relatively blunt measure of one innovation input and some confuse it and the output of scientific papers say with progress in the creation and functioning of an innovation infrastructure. Even so, the EU’s target of being the leading technology economy would have a much better chance if R&D spending were ramped up as proposed by Lisbon.”

Arthurs notes that governments can motivate, but not force, industry to engage in R&D, which is where the big shortfall in the increase in R&D spending in Europe is found. “While photonics benefits from higher R&D spending because photonics tools are used widely in nonphotonics R&D, for the current purposes we should be looking at the investment in photonics,” he says. “I see substantial activity here with German, French, and U.K. photonics strategies, and at the EU level, with Photonics21. I think the latter is an excellent start and we have moved to official recognition of the field as well as some realization of its importance. I feel that the current levels of investment in the future of photonics at the EU level are a factor-of-100 too modest. Some nations in Europe have gotten the message.”

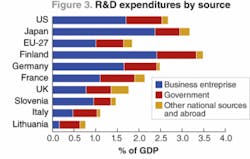

But the question comes back to the simple matter of equating R&D spending with real innovation and what is the measure of innovation? The most recent Eurostat report on the subject suggests a very mixed message, showing that Europe’s top three photonics producers are not necessarily the leaders in overall innovation—if we rate innovation uniquely as a function of collaborative efforts. If we agree with Arthurs’ position, using averages in this way can lead to some very misleading economic data because, even for the purposes of this article, how much of that innovation is in photonics and therefore how relevant is that data to us? The Eurostat report lists R&D expenditures and their sources in what are considered to be Europe’s top three photonics producers, as well as the states that it considers to be the most innovative (see Fig. 3). Is this an accurate portrait of innovation in photonics?In the end, the big EU challenge comes down to getting the funding through to those who can, and will, use it to create a sustainable photonics industry in Europe. The EC has worked hard with Member States, industry, and academia to lay the groundwork for a sustainable photonics industry, but hard questions remain. How long will it take before measurable innovation is seen, and how will it be measured? Will Europeans demonstrate the patience necessary for the plans laid out by the EC to come to fruition? Can Europeans continue to put ego and national identity aside long enough to surmount the challenges of bringing real innovation to market?

Europe has the potential, the resources and, seemingly, the will to become, as the Lisbon Strategy proclaims, “the world’s leading knowledge-based economy,” but maybe just not as soon as its political and industrial leaders would like. Unless, that is, those in a position to do so begin living up to their financial commitments, as well as use more innovative “outside the box” thinking to truly exploit the inherent diversity that is one of the EU’s most precious commodities.

Burgess sees a bright future

Ronan Burgess, of the Photonics Unit at the European Commission Directorate General for Information Society and Media, recently spoke with Laser Focus World about the future of photonics in Europe and the evolving role of the EC, among other topics.

LFW. The EC laid the foundation for Photonics21 and today the organization has over 950 members. As the association continues to grow, how will the EC’s role in the group evolve?

R.B. The EC and Photonics21 have two very different, though complementary, roles to play. The EC provides funding for research and Photonics21 brings together those who are involved in doing the research. The two bodies share the common goal that good science be translated into real innovation.

Photonics21’s first task was to define a Strategic Research Agenda (SRA) that would identify research priorities for European photonics. This SRA was one of the primary sources of input when the photonics objectives in FP7 were drafted. SRA remains a work in progress to ensure that it remains up to date and it will continue to be an important input, not just for the EC, but also for photonics research funded nationally by the European Member States.

The diversity of the Photonics21 membership provides the potential of tackling challenges that go far beyond just formulating research priorities, and the cooperation between the organization and the EC evolves accordingly. Together, we examine each new opportunity to search for ways to create partnerships that will advance European photonics, all the while making it stronger and more innovative. These challenges include the full range of activities from funding advanced research to financing for startups as well as doing our part to ensure that Europe is well equipped for the future with a strong next generation of highly qualified engineers and scientists in sufficient numbers to meet the needs of a growing photonics industry.

LFW. At Photonics Europe, you noted that industrial and research strength are not equal to one another. Historically, the EU is strong in basic and applied research, yet weaker than the U.S. and Japan in experimental development. If we compare invention to research and innovation to industrialization, what role can the EC and FP7 funding play in confirming the EU as the world’s leading photonics innovator?

R.B. The recent study Photonics in Europe: Economic Impact shows that Europe has some very clear strengths in photonics compared to the rest of the world and, of course, some weaknesses. This study, like any study, relies on measuring something that can in fact be measured. In this case, the production of photonics inside Europe was the measurement criterion. Although this is a very pertinent and tangible indicator of where Europe is strong, it does not, however, reflect the totality of European photonics. For example, it does not include other high-value-added activities such as photonics design and research. This is particularly relevant when you look at different European countries, some of which do not yet have an established photonics industry but are nevertheless very strong in research.

That is only one aspect. The other point is that Europe often has the reputation of doing excellent science but not always being able to translate that into innovation and economic growth. This is the big challenge. The role of EC funding is to ensure that research is targeted toward providing real solutions for real needs. This is where Photonics21 makes a valuable contribution. With half of the members coming from industry, it means that research priorities are grounded in practical applications.

However, this does not mean that we should neglect longer-term research. It is essential to monitor emerging technologies that have the potential to revolutionize. In contrast, it is always good to have someone around to ask the awkward question, “Yes, but what can I use it for?” when the pioneering scientists come up with brilliant new ideas.

LFW. The EC’s Photonics21 Mirror Group conceived ERA-NET to stimulate public-private collaboration. Today’s research needs to yield tomorrow’s products for the R&D cycle to function. Will the EC play a role in ensuring the commercial viability of the R&D projects undertaken using public funding in order to encourage a self-sustainable R&D cycle?

R.B. EC funding is in fact only one part of the total funding available for research in Europe. Most funding comes from national research programs. While we do expect to be able to further increase EC funding for photonics, we realize that it will never be enough to meet all the needs of the research community. This is why the EC needs to work together closely with Member States to pool our resources for photonics research.

One of the tools that the EC has to work together with the Members States in research is the “ERA-NET Plus.” This is a mechanism that allows us to create a pot of money to fund photonics research. In this program, the EC contributes one-third and the participating Member States the rest, so that we can create the “critical mass” needed for key research themes. Collaboration with Member States, via the Photonics21 Mirror Group, is achieving the key goal of affording greater recognition for photonics in national research programs.

LFW. EU companies have world leadership positions in certain key photonics sectors that have a particularly heavy impact on environmental issues. Can the EC play a role in fostering cooperation across Member States and various parallel industries to benefit from the long-term potential of environmentally sound technologies?

R.B. The issue of sustainable development is a key topic at the moment and the EC is working on joined-up strategy for sustainable development. Obviously photonics has a key contribution to make here and energy efficiency is receiving a greater emphasis in our research program. In particular, we have highlighted energy efficient lighting and photovoltaics.

LFW. What role can the EC play in ensuring that small- and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) get equal access to new technologies and public funding? Can and should the EC help foster mentoring programs with large, established industrials for smaller, younger companies?

R.B. SMEs are the drivers of innovation and there are a number of ongoing programmes (such as the Competitive and Innovation Programme) which directly address SMEs. In the area of photonics, SMEs play a particularly significant role, particularly in the regional photonics clusters. Twenty percent of all EC funding in the photonics area goes to SMEs. In addition, we have introduced specific actions that are designed to give SMEs access to advanced photonics technology. In FP7 in general, the involvement of SMEs is supported by providing them with a higher level of funding than that allocated to larger companies—75% compared to 50% for larger companies.

LFW. In your presentation, you talked about education being an essential element to the EU’s success. What role can the EC play in harmonizing educational standards across Europe? What role should industry play in this essential investment in our future?

R.B. We see the area of education and training to be an essential topic for the future of any high-tech area but particularly for photonics. This is an area where we would like companies to work closely with academia.

University education needs to be more closely geared toward the needs of industry, emphasizing a multidisciplinary and systems-oriented approach, and industry needs to play an active role in this process. We need to create an environment where industry and universities can form real partnerships. After all, the growth of industry is very dependent on the availability of a pool of qualified scientists and engineers with the right mix of skills—not just technical competences, but equally business skills. An essential ingredient for this is encouraging more young people to get involved in science. Outreach to younger people is where companies can also play a key role. This topic is so important that we need to get everybody involved who has something to contribute.

Mark Zacharria | Mktg/Comms

Mark Zacharria is cofounder and senior consultant of Elucido Partners (Paris, France).