OPTICAL STANDARDS: US optics standards need change

Standards are involved in everything we use, from the ATM cards in our pockets to the font shapes in this article. Standardization facilitates commerce and allows us to be more efficient in our work and in our lives. Optics specification, drawing, and metrology standards are an essential component of the optics and photonics industry. And yet, despite their ubiquity and utility, most people using these standards are only marginally aware of their existence, or that the standards used in the industry today are the result of the work of a handful of professionals.

Much of the bedrock of commerce, including trade rules and currency, began as top-down standards imposed by a controlling power. In the US photonics industry, most of our standards—such as the format of our optics drawings, the specification of roughness, and the ever contentious and misunderstood scratch-and-dig specification—began as top-down standards from the US military.

Increasingly, though, these top-down standards are being replaced by voluntary industrial standards, which are controlled not by the government or the military but by industry associations and organizations. And rather than being proclamations of the right way to do things, they are more often documentation of the best standard practices in the industry.

This era of voluntary industry standards dates back to the industrial revolution, when railroad companies began adopting standard rail gauges to facilitate interconnection of railways in the 1840s. Later in the 1800s, the railroads and other businesses adopted standards for fasteners such as screw, bolt, and nut threads, in the interests of facilitating commerce. Often, each industrial and business association and regional organization would advocate its own standard as the best practice over other, competitive standards. As a result, multiple standards would emerge as prevalent for an industry or region, and typically one would be selected from those in use.

International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

By far the largest force in the world today for standardization is the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), based in Geneva, Switzerland. Formed in 1926 as the International Federation of the National Standardizing Associations (ISA), it began as an international effort to standardize mechanical engineering components. The ISA was suspended during the Second World War and then reconstituted in 1946 under its current name. The organization is based on a one-nation, one-vote system, with volunteer experts developing the standards themselves as representatives of their national member bodies. Today ISO boasts 165 member nations and chairs more than 2700 technical committees, subcommittees, and working groups.

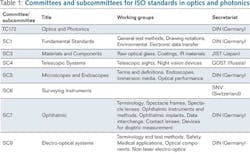

The standards for optics and photonics are developed by Technical Committee 172, which was formed in 1978 and has a total of 15 participating members, managing about 300 standards and technical reports (see Table 1). Even so, a typical standards meeting within TC 172 will have between one and two dozen experts from a small subset of the participating members.

The US representation is administered by the Optics and Electro-Optics Standards Council (OEOSC) under the auspices of the American National Standards Institute (ANSI). OEOSC also administers the American Standards Committee for Optics (ASC OP), which is responsible for all American national standards for optics and electro-optics except for those of the ophthalmic industry, which are managed by ASC Z80.

OEOSC and ASC OP

OEOSC is a standards council made up of companies and corporations, organizations, institutions, and individuals with an interest in standardization in the optics industry in the US. It was formed in 1996 as a merger between the standards-writing bodies of SPIE, OSA, APOMA, NAPM, and Eastman Kodak. Since then it has grown to more than 70 members and is now an important force behind national and international standards for optics. It is managed by a board of officers and directors who are members of the optics community. The annual meeting is typically in San Francisco, CA, in conjunction with the SPIE Photonics West conference.

At the international level, OEOSC oversees all participation in TC 172 and has been actively managing the standards development efforts of the general subcommittees SC1 (fundamental standards) and SC3 (materials and components), which are not connected to any specific industry. Members of OEOSC have participated in the development or revision of some of the most important standards in our industry, including all parts of ISO 10110 (the international drawing standard) and ISO 9211 (the standards for optical coatings).

In addition to its international standards efforts, OEOSC is also the secretariat for ASC OP. With more than 40 members from across the industry, ASC OP has representation from manufacturers, users, universities, and trade organizations. There are six task forces (TFs) within ASC OP and sixteen concurrent standards-development projects in process. Current projects include revising the glass standard OP3.001, developing a new edition of the popular OP1.002 for surface imperfections, developing a suite of standards for the testing of optics including aspheres, and adopting the various parts of ISO 10110 as the American National Optics Drawing standard, which will be called OP1.0110, Parts 1-18.

Participation varies widely for the various task forces; some TF meetings have five or six attendees, while others include more than 50. Even so, the actual writing and editing of standards tends to be the work of a handful of experts, even in the largest committees.

Snapshot of current standards in general optics

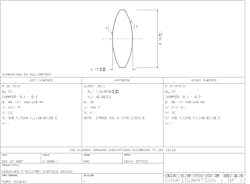

There are times when we use standards and don't even realize it. Take a typical biconvex lens, drawn using one of the popular automated optical-design programs. Most optics drawings are drawn to ASME-Y14.18M-1986 or its predecessor, MIL-STD-34, which describes the 2D cutaway drawing, the notation of the radius and form, and the long list of common notes.

The surface-quality requirement is given as a scratch-and-dig specification (for example, 80-50 or 60-40), which harks back to OP1.002 or its predecessor, MIL-PRF-13830B, whether the standard is referenced on the drawing or not. Surface texture might be given as "10 Angstroms rms," a form that dates back to the old MIL-STD-10A, which had default specifications for spatial bandwidth that allowed such a simple callout to be valid. And almost all glass specified in the US is based on MIL-G-174B.

The problem is that most of these old MIL standards have been withdrawn or inactivated. In 1994, the Secretary of the Armed Services issued a directive stating that in the future all military procurement contracts should refer to national and international commercial standards rather than military specifications.

To date, more than 7000 military specifications have been canceled. Of the 55 military specifications that relate to optical products, half have been canceled and one-quarter have been declared inactive. Inactive specifications can be used for existing procurement contracts but not for new ones. The optical manufacturing community in the United States must adopt ISO standards or develop new voluntary commercial optical standards to fill the void left by the absence of these military specifications.

For example, with the withdrawal of both MIL-STD-34 and ASME-Y14.18, there is no comprehensive American national optics drawing standard at this time; this is why ASC OP is working to release a new series of notation standards, OP1.0110, as an American version of ISO 10110. Two parts of the ISO's optical drawing standard have already been modified and adopted. A lens drawn using ISO 10110 is significantly different from the old MIL standard format, and can be more difficult to understand for American manufacturers (see figure). To minimize confusion, optics engineers must become more diligent about identifying which standards they are intending to invoke with their notations for roughness, glass grades, or scratch-and-dig quality.

Table 2 identifies some of the domestic (ASC OP) and international (ISO) standards with general application to optics. Some standards are devoted exclusively to measuring techniques; others are devoted exclusively to the language and symbols to be used on a technical drawing (blueprint); some combine both scopes. For more information, please visit www.opsd.org. Both the ASC and the ISO sets are works in progress; they are being actively developed at this time, but neither set is complete.The future of standards

It is imperative that there be broad industry and government participation in the development of optical standards so that the resulting documents adequately meet the needs of all optics manufacturers and customers in the US. The same participation is required to ensure that international optical standards are developed in a way that guarantees competitiveness of the US optics industry in international commerce.

The one-country, one-vote system provides an inherent advantage to the closely aligned European delegations, while the higher fees for US participation (such fees are determined by gross domestic product) and the tradition that there are no government subsidies or funding of standards participation place the US at a disadvantage. This means that volunteers from across the US optics industry are needed to donate their time and expertise in the development of new national standards, as well as in the review and balloting of new ISO standards.

Experts from all optical manufacturing companies and government agencies, and the general public as well, are invited to join the ASC OP committee and the US technical advisory group (TAG) to ISO/TC 172. Information concerning participation can be found on the OEOSC website (www.opsd.org). Alternatively, requests for information can be made to Dave Aikens, executive director, at P.O. Box 25705, Rochester, NY 14625; phone 860-878-0722; fax 585-377-2540; e-mail [email protected].

David Aikens | President and Founder

Dave Aikens is president and founder of Savvy Optics Corp, a Connecticut optics company dedicated to serving the optics industry through practical optical design and engineering, and offering products and training that is required for the 21st century. Before striking out on his own, Dave was in the metrology engineering group at Zygo Corporation, the optical engineering group at Thermawave (now KLA-Tencor), and the NIF optical design and fabrication group at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. He has been working on national and international optics standards and specifications for more than 15 years.