The global market: From pre- to post-pandemic times

The COVID-19 pandemic has changed our behavior, particularly in relation to the economy. It was unavoidable, according to Dr. Anirban Basu, chairman and CEO of Sage Policy Group. Kicking off the 2022 Lasers & Photonics Marketplace Seminar in January 2022, he dived into the global market—from the industry’s current economic conditions and what brought us here to expectations for a post-pandemic world.

At the start of the pandemic in early 2020, many expected the economy would halt for a few weeks, Basu notes. “And then we would quickly re-establish the status quo ex ante. But now, we’re headed to the completion of two years of this. That’s enough time to change behavior. And anything that changes behavior, alters economic outcomes.”

The U.S. economy declined 3.4% during 2020, as restaurants and entertainment venues (among other “nonessential” businesses) were forced to close amid quarantine mandates. Other North American countries felt the hit, too: Mexico saw an 8% decrease, and Canada’s economy was down more than 5%. European nations found themselves in similar positions that year, according to Basu. In Germany, there was a nearly 5% decline; France saw an 8% hit; Italy’s economy was down nearly 9%; Spain’s economy declined 11%; and the UK suffered a nearly 10% decrease.

This widespread decline can also be attributed to tourism. Places such as the Caribbean and the Virgin Islands were hit—both of their economies rely heavily on tourism.

So, Basu says, our collective loss became other economies’ gain. “We couldn’t take vacations, we couldn’t go out as much. So, people ended up buying toaster ovens or whatever, which are often made in China. Spending on services went down and spending on manufactured items went up.”

That increased demand for household goods helped push China’s economic expansion in 2020; this country makes up 25% of global manufacturing and touts the world’s second largest economy. The events of that year stimulated their supply chain, adding to the success of the global supply chain.

Agriculture-extractive industries experienced growth as well. Guyana (South America), for instance, is currently the fastest growing economy in the world, according to Basu, thanks to bauxite—a sedimentary rock that is the key component of aluminum—found there. It’s one of the main commodities the country depends on; this is beneficial, particularly now, as aluminum prices have been at record highs.

Other natural resource-intensive societies also grew economically—in Western Africa, for example, and specifically Guinea. In 2020, this small country produced 22% of the world’s bauxite.

“Natural resource-intensive economies in many cases, including Western Africa, tend to hold up better than others,” Basu says, citing Ethiopia. In 2020, it was the third-fastest growing economy in the world. Its government invests a lot in infrastructure and touts an economy that shifts from agriculture to services. He adds that Ethiopian people are “wildly entrepreneurial” as well.

Ireland, a small trade-dependent economy, is another example of financial growth in 2020. According to Basu, Ireland is home to a lot of multinationals, which in many cases are technology companies—they vastly increased exports that year. The country’s domestic demand declined 5.5%, but this “export boom” allowed the country to grow economically. He calls this a miracle, in part because “when you look at the volume of global trade in 2020, it collapsed. But not with respect to the exports of technology, and that’s an Irish specialty. That’s one of the reasons that economy really took off.”

But, circling back to other nations’ economies, Basu compares the global economic situation to the story of Humpty Dumpty.

“Economy is an egg and it got broken,” he says. “But it gets broken in some places more than others because the shutdowns, the lockdowns were more aggressive in certain societies than others. We didn’t see the kinds of shutdowns in Western Africa, for instance, that we saw in the U.S. or Europe or Australia or elsewhere in the advanced world. Those kinds of results make a difference.”

Current economic conditions

“A lot of economists are racing back to try to put that superstructure back together,” Basu says. However, this has been difficult given the 2020 collapse of foreign direct investment—it fell 35% that year, according to the United Nations Conference on Trade Development. “One of the other aspects of this is the falloff in global trade’s inflationary pressures.”

He notes that Americans, for example, have benefited greatly from better integration with the Chinese economy and the Mexican economy in terms of keeping prices low. That said, “there have been some costs to that as well—a lot of loss of jobs in the industrial sector and that kind of thing.” Basu cites the recent surge in inflation, too, “not just in the U.S., but globally.”

“A lot of that has to do with the fact that global trade is fragmented,” he says. “And all of a sudden, people in the world are somewhat disparate and separated. Global supply chains are fragmented, and what do you get? You get higher prices.” He adds that some of the jump in inflation has been driven by monetary policy, according to the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The FOMC has also cited transitory factors—economic growth and decline, changes in the job market, among them—as a reason for the rise in inflation. Now, they add “supply and demand imbalance related to the pandemic” to the mix, as well as “the reopening of the economy [that] have continued to contribute to levels of inflation transferring this debt.”

According to Basu, these issues have been exacerbated by waves (variants) of the virus. Inflation overall has been rising above the standard 2% goal and will likely continue to do so throughout 2022. “Consumer inflation has been running at 7% on a year-over-year basis,” he says.

Inflation can also be attributed to growth and changes in money supply. To better explain this, Basu introduced the “equation of exchange” (or “quantity equation”): M (money supply) times V (velocity of money) equals P (aggregate price level in the economy) times Y (output of gross domestic product). Basically, the money supply times velocity tells you the amount of money available to finance transactions, which equals what products are available to be purchased times the price of those products. The percent change in aggregate price levels is inflation.

“When you increase money supply, as the Federal Reserve did, two things can happen,” Basu says. “One is inflation, and one is increase in output. But here’s the issue. The Federal Reserve has known that global supply chains have been buckling, that we don’t have enough truck drivers to move goods around. We don’t have enough construction workers, manufacturing workers. It’s not just an American problem. We don’t have enough computer chips, so you can’t manufacture vehicles. Output is constrained in terms of growth. So, when they increase money supply, much of the burden goes on inflation.”

Government finance officials are now recognizing the problem is more than transitory, and getting “set to dramatically change monetary policy,” beginning with quantitative easing.

“This expectation is that they will raise short-term interest rates four times this year,” Basu says, which is according to the Goldman Sachs chief economist, Jan Hatzius. “This is their reverse course. And that's one thing to think about when you talk about the outlook for the economy going forward.”

Another driver of inflation, Basu says, is the “functioning of the labor market, or rather the dysfunction in the labor market.” Employment rates were down overall in 2020. The hardest hit here was in youth employment. Youth employment rates declined in advanced economies as well as in emerging markets/developing economies. In the emerging markets, in particular, “13% of all youth employment was destroyed.” Citing a report by Sage Policy Group, Basu noted that in both advanced economies and emerging markets/developing economies, men tended to lose jobs more than women. And lower-skilled workers lost more jobs than higher-skilled workers.

This prompted the onset of government stimulus funds in America. The Coronavirus Aid Relief and Economic Security Act (CARES Act), signed in March 2020, provided more than $2 trillion in direct payments, which included stepped-up and extended unemployment insurance benefits, as well as loans and grants to businesses, and the “paycheck protection program.” A second stimulus package was enacted a few months later.

At that point that year (March), the U.S. reported the loss of 1.7 million jobs. In April, 20.7 million jobs we lost. According to Basu, this amounts to “as many jobs as we had added in the previous 113 months [nearly 10 years].” But the stimulus programs ultimately led to the addition of millions of jobs—between May and August of 2020, nearly 31 million jobs were added.

“So, we’re coming back [at that point]. The stock market is booming, the housing market is booming,” Basu says. But this didn’t last. “By the fourth quarter, momentum is fading. Retail sales are sliding by October, and by December, we’re losing jobs again.”

More stimulus money was endowed in late 2020 and again in early 2021; in total, the U.S. has allocated $6 trillion in stimulus funds since the start of the pandemic. This strengthened the U.S. economy, with aspects such as a decline in interest rates, but also has resulted in a lot of debt. “If you look at the most recent data,” Basu says, “we’re close to $30 trillion in national debt. Now, if I am a C-level executive as part of an enterprise in the photonic segments and I’m doing my [strategic planning and strategic management] analysis, I’ve got to think that the U.S. national debt or global debt generally has got to be at or near the top of my threat assessment.”

America is not alone in its high debt levels. The general government gross debt as a percentage of GDP in advanced economies is expected to report in at more than 121% for 2021. Debt in emerging market economies also went up—it’s projected to hit 63.4%.

The forecast

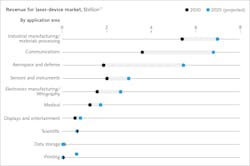

A report by financial consultant McKinsey & Company projects an annual growth rate for the laser device market of about 10% through 2025—increasing from $17 billion in 2020 to $28 billion (see figure). The general economy is predicted to grow 5.2% in 2022; Basu disagrees.“I don’t see how we get to 5.2% in this country,” he says, citing issues with the global supply chain. “We don’t have enough workers to get us there. We have a shortage of 80,000 truck drivers.”

Shipping costs over the past two years have been extraordinarily high, Basu says. “It’s one of the reasons the global supply chain has been so fractured. Because it’s so difficult to ship inputs in an economically efficient manner.” But now, some shipping costs have begun to subside, thanks to the larger shippers that dominate the market. Collectively, those shippers recently ordered “more containerized cargo ships to be built for them than in the history of humanity.” While it will take a little time, he says, “you can already see some evidence of improvements in the global supply chain. Shipping costs are falling and that’s been one of the things that we really needed to get the global economy to take off.”

“Collectively, the consumer is loaded,” Basu says. “They’ve got about $3 trillion in surplus savings above and beyond what they would have saved if not for the pandemic, so the consumer is ready to go.”

He—along with some other financial analysts and officials—anticipates that by April this year, the pandemic will have subsided, and the economy will begin to show noticeable improvements. Growth of the macroeconomy should be supportive to photonics and lasers, according to Basu. For the U.S. economy, he forecasts 3 to 4% economic growth this year in GDP.

“I think it will be a year of growth in America,” Basu says. “I think it'll be a year of growth for the global economy.”

CONTINUE READING >>>

About the Author

Justine Murphy

Multimedia Director, Digital Infrastructure

Justine Murphy is the multimedia director for Endeavor Business Media's Digital Infrastructure Group. She is a multiple award-winning writer and editor with more 20 years of experience in newspaper publishing as well as public relations, marketing, and communications. For nearly 10 years, she has covered all facets of the optics and photonics industry as an editor, writer, web news anchor, and podcast host for an internationally reaching magazine publishing company. Her work has earned accolades from the New England Press Association as well as the SIIA/Jesse H. Neal Awards. She received a B.A. from the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts.