GREGORY FLINN

The European Commission’s Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development is Europe’s main instrument for funding research. The current Framework Programme (FP6) covers a five-year period from 2002 until 2006, with a total budget of nearly €18 billion (US$22.6 billion). Following a critical assessment of FP6, the Commission proposes some important changes for FP7, which begins in 2007, including a significant increase in the overall budget, a seven-year time span, and a streamlining of application, funding, and management procedures.

As in previous Programmes, collaborative research will constitute the bulk of EU research funding in FP7. The objective is to establish, in the major fields of advancement of knowledge, outstanding research and networks able to attract researchers and investments from Europe and the entire world.

Within the Framework Programme, technology platforms such as Photonics21 are intended to play a major role in ensuring that the new strategy is realized with the help of the industrial sector. The goal is to advance the worldwide competitiveness of the European Research Area by establishing a common vision for technology development for all FP-relevant research areas.

Background and philosophy

The Framework Programme is a series of multi-annual, European-wide funding schemes that have been running since 1984. Rather than awarding funding to individual research groups, the raison d’être of the Framework Programme is to promote interdisciplinary, cross-border collaboration between research and industry, with the long-term rationale of improving the competitiveness of European Research and Technological Development (RTD) on a world-class level.

The long-range goals of the Framework Programme generally represent a subset of those adopted by the European Commission (EC) for the EU as a whole. Preceding FP6 in March 2000, for example, European leaders had adopted the “Lisbon Strategy” (or Lisbon Agenda).1 The Lisbon Strategy represents a commitment that the EU becomes by 2010 “the most dynamic and competitive knowledge-based economy in the world capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion and respect for the environment.”

Motivation for this commitment included the strength of the United States economy, which was at the time building on the emergence of the so-called new “knowledge economy” and its leadership in information and communication technologies. Additional factors included the level of research funding relative to GDP made within the EU as a whole, in particular in comparison to similar figures for Japan and the United States-in 2003 roughly 1.9%, 3.1%, 2.6%, and 1.3%, respectively, for the European Union, Japan, the United States, and China.2 The EC thus laid down policy for achieving the goals of the Lisbon Strategy.

The relevance of this policy lies in its influence on the development of the European (photonics) industry. Creative interaction between academic research and industry is a crucial path for technology transfer, but is heavily dependent on the close physical location of universities and companies. The availability of a suitably qualified workforce to support this transfer, during innovation and in development, is also paramount.

It was also recognized that Europe’s future economic development would depend on its ability to create and grow high-value, innovative, and research-based sectors capable of competing with the best in the world.

Likewise, it was decided that Europe needs to dramatically improve its attractiveness to researchers in all fields, as too many young scientists continue to leave Europe after graduation, notably for the United States, and too few of the brightest and best from elsewhere in the world choose to live and work in Europe. Finally, there were financial questions requiring attention, such as the problem of funding for universities, as well as remuneration and career advancement issues.

Framework Programme 6

The current Framework Programme, FP6, is based around the concept and formation of a European Research Area (ERA).3, 4 This feature of FP6, also scheduled to continue through FP7, equates to the realization of a single research environment within Europe that is as internationally recognizable as the single common currency (Euro, €) or the EU single market itself.

Funding is awarded under FP6 for research in seven thematic priority areas: life science, genomics, and biotechnology for health; information society technologies; nanotechnology and nanosciences; aeronautics and space; food quality and safety; sustainable development, global change, and ecosystems; and citizens and governance in a knowledge-based society. In addition to these seven areas, an eighth sector of research on nuclear safety is included, in line with the EU’s responsibilities under the Euratom Treaty.5

To help implement the goals of FP6, two new instruments have been created-Integrated Projects and Networks of Excellence. The former are multipartner collaborations of substantial size, designed to help build up the “critical mass” in ambitious objective-driven research, delivering either leading-edge expertise for Europe or addressing major societal issues. The latter are designed to induce a progressive and lasting integration of expertise within the EU and thus make a major contribution to the concept of the ERA.

PhOREMOST is a Network of Excellence (NoE) for Nanophotonics and Molecular Photonics specializing in nanoscale materials and structures, as well as their fabrication and characterization, with the goal of addressing the requirements for functional, molecular-scale photonic components. NEMO is a Network of Excellence on Micro-Optics specializing in the manipulation and management of photons with micron-scale structures, seen as a key link between photonics and nanoelectronics.

Just two of more than 120 Networks of Excellence—with perhaps a dozen related to optics, photonics, and nanotechnology—these groups each comprise more than 30 principally academic partners providing forefront scientific and technical services to the photonic community through established service centers. In addition, NEMO offers a Directory of European Photonics Expertise in Research (DEPER), a database of institutions, universities, and SMEs (small- to medium-size enterprises) looking to increase their involvement in EU-funded research. Although principally designed as a forum for bodies from new Member States, registration on the database is open to all (see www.micro-optics.org).

Moving on to FP7

The Framework Programmes are all subject to continuous review, and the effectiveness of the new instruments introduced in FP6 has also been assessed. Changes in policy recommendations arising out of these reports have been put forward to FP7.6

In its content, organization, implementation modes and management tools, the next Framework Programme is also a critical component of the relaunch of the Lisbon Strategy.

FP7 is organized into four specific cornerstones, defined to best represent the updated objectives of EU research policy: cooperation – promotion of collaborative, cross-border research in order to regain world-class scientific and technological leadership; ideas – as represented by the establishment of a European Research Council to nurture ground-breaking research carried out by individual teams; people – improvement of training, career prospects and mobility of European researchers as represented by a coherent set of Marie Curie Actions (see “A wealth of information on the Web”); and capacities – the development and full utilization of the EU’s research capacities through large-scale research infrastructure, regional cooperation, and innovative SMEs.

A wealth of information on the Web

General information on all aspects of EU-funded research can be found on the Web at europa.eu.int/comm/research. While complete details are, in principal available, from this Web site, the Community Research & Development Information Service (www.cordis.lu) is the official information dissemination service for the European Commission and has detailed Web sites for the current and next Framework Programmes. Both the EC and the CORDIS Web sites are a veritable, occasionally overwhelming, gold mine of information and documentation, providing details on policy decisions, Framework Programme progress, assessments, the thematic priority areas and participation, as well as documentation on such aspects as eligibility, partner search, and the application procedure. It is best to use both sources when seeking information.

EurActiv (www.euractiv.com) is an independent media portal fully dedicated to EU affairs. This portal publishes the latest developments regarding political and administrative topics pertaining to EU policy. Science and Research policy decisions and developments are also featured heavily (www.euractiv.com/EN/science), with the additional benefit that these are also cross-linked to other (relevant) topics outside of R&D. The site is available in English, French, and German, and presents a serious alternative for following up on some of the information provided here, either in detail or in the wider context of EC policy in general.

Complementary to the funding of research programs, the EC offers a series of Marie Curie Actions to help highlight the importance of researcher mobility as associated with collaborations approved for funding under FP6 or FP7. By facilitating the transfer of expertise within and into the EU, as well as widening career prospects of researchers, these Actions present a coordinated attempt to make the ERA more attractive to researchers internationally.

Note that with the recent introduction of the “.eu” Web site addresses, all of the links given here may soon change, although forwarding links are expected.

In recognition of its critical importance to future European RTD leadership, the European Council has agreed that overall R&D spending in the EU should be significantly increased, with the aim of approaching 3% of GDP by 2010. Two-thirds of this new investment is to come from the private sector.7 Few EU countries already exceed this level of overall and business-sector investment-Sweden, Finland, and Iceland.2

Although the total funding for FP7 was originally proposed to be some €73 billion (US$91.5 billion), latest EC negotiations suggest that this figure is likely to be closer to €50 billion (US$62.7 billion). This sum still represents a significant increase over that allocated to FP6, but note that the EU recently grew to 25 Member States and FP7 was changed to a seven-year term.

The latest EC proposal envisages starting in 2007 with around €5.1 billion (US$6.44 billion) with gradually increasing annual expenditure to reach €8.9 billion (US$11.23 billion) in 2013. In real terms the overall budget increase amounts to around 40%, while the allocation for 2013 equates to an increase in the yearly budget of 75%. Cooperation and Ideas will receive around 75% of the funds, People and Capacities around 20% and the remainder will go to the Euratom (nuclear) and JRC (non-nuclear) activities.

The qualifying research fields for FP7 were published in September 2005. All FP6 thematic priority areas remain with some restructuring, so that the addition of “Space & Security” brings the total number of thematic priority areas to nine (see table, below). All these areas form the Cooperation pillar of FP7, and the first call for proposals is expected to take place in November of this year. As with previous Programmes, collaborative research will constitute the bulk of EU research funding.

| Thematic priority areas of FP7 (funding € millions)* | |

| Health | 8,317 |

| Food, Agriculture & Biotechnology | 2,455 |

| Information & Communication Technologies | 12,670 |

| Nanoscience, Nanotechnologies, Materials, and new Production Technologies | 4,832 |

| Energy | 2,931 |

| Environment (including climate change) | 2,535 |

| Transport (including aeronautics) | 5,940 |

| Socio-economic Sciences & Humanities | 792 |

| Security & Space | 3,960 |

| Source: CORDIS *Numbers shown are for the original proposal and are likely to be about 30% lower when FP7 commences | |

Other changes include a simplification and rationalization of administrative issues (application, funding, and management), and improvements in benefits, opportunities, and mobility for researchers. Further recommendations still on the table include simplification of the patent procedure, at least on a European-wide level, and the establishment of an EC patent.

Another common concern was to decrease the number of partners in consortia and to provide a greater focus on smaller projects than has been the case under the FP6. All of these steps should in particular benefit smaller countries, smaller research teams, and SMEs.

The final key component is the formation of a European Research Council (ERC) to help coordinate funding and long-term basic research at the European level. The ERC forms the principal element of the Ideas pillar of FP7 and will be supported through funding amounting to €7.5 billion (US$9.47 billion).

As pointed out by Henri Rajbenbach of the European Commission, photonics precipitates out directly in only two of the nine thematic priority areas in FP7, namely information and communication technologies, and nanosciences. However, any of the generally recognized fields for photonics can either be slotted directly into any relevant thematic priority area, or appropriate topics can be positioned as a cross-thematic collaboration.

Participation in any project is perhaps easier than most may believe (see “Members and non-Members can participate”), although, as always, cross-border cooperation and a European location remain the major prerequisites for receiving funding.

Members and non-Members can participate

An important aspect of the Framework Programme is the encouragement of international cooperation, and additionally, through outstanding research and technological advances, to promote the concept of a European Research Area.

Any university, research institute, or private company located in any one of the Member States is entitled to direct participation and thus also to funding. The prospects for organizations within non-Member States is also good—any legal entity from any country in the world may participate, but there are different rules addressing participation and funding for specific classifications of countries (www.cordis.lu/fp6/stepbystep/who.htm).

For any company not directly eligible, and neither eligible via any of the classifications listed above, participation in an EU collaboration and access to funding remains via two avenues—either the company has a subsidiary within the EU, this subsidiary being itself entitled to direct participation just as for any other European enterprise; or firms may seek to partner with a European firm that is itself eligible.

For U.S. firms, help is available in the form of information, as well as assistance in finding partners, through the U.S. Commercial Service (www.buyusa.gov/europeanunion).

Photonics technology platform

Although perhaps not yet generally recognized as a major industry, photonics has certainly been recognized as an important aspect of RTD within Europe and indeed around the world. The importance of photonics lies not only in the direct value of the optical components markets, but rather far more as an enabler for a broad range of industrial markets and services.

As highlighted by Viviane Reding (the EU Commissioner for Information Society and Media) at the April Photonics Europe meeting in Strasbourg (see www.laserfocusworld.com/16546739), the communications infrastructure and the service industry made possible by deployment of photonics components represent industries some 80 times larger than the market for the components alone.

Moreover, many of these markets, either direct or indirect, are seeing double-digit growth rates—materials processing and high-brightness LED applications are just two high-profile, high-growth market areas in which photonics features heavily and where European industry is at the forefront (see Fig. 1). These, together with display technology, lighting, health care, metrology, and process control are just some of the applications that, according to Reding, will benefit from a strategic agenda, in particular by focusing resources on activities presenting the greatest potential to deliver a return on investment.

This key feature of FP7 highlighted by Reding-the focusing of research priorities and industrial commitment through strategic agendas-is designed to form the basis for medium- to long-term policy making. Categorized under the Joint Technology Initiatives and Technology Platforms, these programs are intended to play a major role in ensuring that the new FP strategy is realized with the leadership and backing of the industrial sector.7

While the Joint Technology Initiatives are designed to make public sector investment in RTD more appealing, the Technology Platforms have been devised to actually bring the technology stakeholders together in the first place—industry, research, public authorities, as well as regulators and policy makers. By transforming a common vision for investment in R&D, innovation deployment, and technology development into a Strategic Research Agenda (SRA)—not just in photonics, but for each FP relevant research area—the aim is to regain the leading edge in forefront technology and to establish the ERA as a world-class location.

To date, 29 Technology Platforms have received official approval from the EC to tender an SRA for shaping FP7 policy and goals. The Photonics21 Technology Platform was launched at Photonics Europe.8

Under the voluntary leadership of key figures in European Industry-including major industry representatives from Trumpf, Bookham Technology, Carl Zeiss, Jenoptik, Philips Lighting, BAE Systems, Rofin-Sinar Laser, among others-Photonics21 has put forward a Strategic Research Agenda for the development of photonics technologies under FP7.

Photonics21 currently embodies more than 350 representatives from academia, research institutes, SMEs, and industry across Europe. Of these 350 members, almost 50% come from industry, and three quarters of these are SMEs. The other half are organizations working in the boundary formed where scientific expertise is transferred into industry.

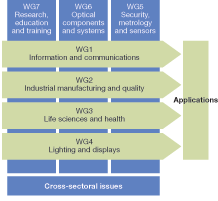

The members are formed into seven working groups, and each was given the task of addressing a single major discipline in the field of photonics (see Fig. 2). The sum of their work, representing recommendations for technology adoption and research strategy in the short and long term, forms the bulk of the Photonics21 Agenda document.

Entitled “Towards a Bright Future for Europe,” the Photonics21 Strategic Research Agenda encompasses two core aspects—higher European and national expenditure on R&D in photonics and a pan-European strategic approach. In addition to renewed emphasis of the FP7 policy recommendations with specific regard to photonics, supplementary objectives include the systematic evaluation of those R&D efforts will lead to marketable products in ten years, and cooperation with corresponding Technology Platforms.

The Photonics21 Agenda also recognizes the call for increased R&D spending by the industrial sector up to levels seen in Japan, Asia, and the United States. Alexander von Witzleben, president of Photonics21 and CEO of Jenoptik (Jena, Germany), has already announced a plan by industrial members of Photonics21 to meet this challenge.

In real terms the overall spending (national and EU) is quite respectable—€195 billion in 2004 compared to €120 billion in Japan, €252 billion in the United States and €16 billion in China (all for 2003)—with almost 55% coming from the business sector. Nevertheless, in relative terms the EU lags behind both Japan (3.1% of GDP with 75% from the business sector) and the United States (2.6% and 63%, respectively).2

Increased spending alone is, however, not the only requirement. “Although Europe’s photonics industries have some coordination at the national level, we need to have better coordination across the EU,” von Witzleben said. Other key challenges highlighted in the Agenda include improving coordination of European standardization as well as securing a qualified workforce for future industrial development.

Of course, whether all this planning will result in real action remains to be seen. There are those within the community who admit to some skepticism.

As pointed out by Bernd Schulte (VP and COO of Aixtron) together with Henri Rajbenbach at the launch, the Photonics21 SRA is a living document, and yearly adjustments are planned. Anyone associated with research and innovation in the European arena is invited to help shape the agenda, remembering that the Technology Platform is, by definition, industry driven and “not for fundamental science.”

It is only fair to note that Photonics21 is not the only policy-shaping organization operating in alliance with the EC. In particular, researchers facing the transition from FP6 to FP7, or organizations located in new Member States seeking information, can find help in the form of NoEs (such as through DEPER) and through OPERA-2015.9 Funded through FP6, OPERA-2015 can best be described as a cluster-like resource to anyone seeking information, funding, and networking options on a national or European level, and has until recently perhaps represented the foremost and broadest attempt to define photonics R&D policy under FP6.

The European Commission’s commitment to assisting the transition from pure R&D to industrial exploitation can be clearly seen in the instruments created to help facilitate this transition—the European Research Council to nurture pure forefront science, Networks of Excellence to transfer leading-edge science and expertise into industry, and the new Technology Platforms as a forum for shaping industrial involvement and leadership. These Platforms bring new emphasis to the need to target technologies with a potential to yield return on investment, and this will be reflected in the nature of R&D that receives funding under FP7.

While at first glance rather overwhelming, participation, application, and activities of the Framework Programmes are actually well structured and served by comprehensive information portals. Streamlined administrative procedures and encouragement of smaller collaborations in FP7 should simplify the participation of research and industry, in particular for those from smaller countries and those from new Member States.

Should the goal of an internationally respected European Research Area become realized as a result of the policy adopted in FP7, non-European research and industrial organizations may want to note the developments driving (photonics) RTD within Europe, and look more closely at the opportunities for involvement presented to the international community in general.

REFERENCES

1. www.euractiv.com/en/agenda2004/lisbon-agenda/article-117510

3. cordis.europa.eu/fp6/whatisfp6.htm

4. cordis.europa.eu.int/era/concept.htm

5. www.cordis.lu/fp6-euratom/home.html

6. www.cordis.lu/fp6/find-doc-general.htm

7. europa.eu.int/invest-in-research/index_en.htm

Gregory Flinn, “Putting Photonics into Context,” writes extensively on the European photonics industry; Deutingerstrasse 16, 82487 Oberammergau, Germany; e-mail: [email protected]; www.gregoryflinn.net.