'Tamper-proof' anticounterfeit hologram is sculpted by UV laser directly into metal

A tamper-proof hologram that is scribed directly into metal or glass using an ultraviolet (UV) nanosecond-pulsed laser is being developed that could replace serial numbers and barcodes, reducing the trade in counterfeit goods.1

Manufacturers of high-value goods such as electronics and aviation parts etch serial numbers into products, use bar codes, or place polymer holographic stickers on the items to provide identification and traceability of products and to assure customers of quality. However, serial numbers and bar codes can be damaged and stickers are vulnerable to tampering and counterfeiting.

Scientists led by Duncan Hand at Heriot-Watt University (Edinburgh, Scotland) are using the UV laser to sculpt holograms with microsized features directly onto the surface of metal parts, making the holograms tamper-proof.

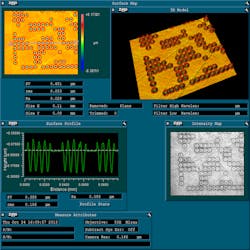

Individual laser pulses provided at a rate of a few kilohertz (see figure) melt the surface in a precise, localized way to produce optically smooth impressions on the metal. By manipulating the laser beam to create specific patterns, holographic structures are produced that can act as security markings for high-value products and components.

"The holograms are visible to the naked eye and appear as smooth, shiny textures," says Krystian Wlodarczyk, one of the researchers. "They’re robust to local damage and readable by using a collimated beam from a low-cost, commercially-available laser pointer, so border agencies or consumers won't need expensive technology to check an item’s authenticity. Actually, the holograms can also be read even using a 'flashlight' from a smart phone. We've established that we can create the holograms on a variety of metals. We’re now investigating how to make them even smaller and more efficient and whether we can apply them to other materials. Recently, for instance, we have extended the process for use of such holograms on glass."

The holograms can generate diffractive images containing alphanumeric characters or logos: the structure of the hologram is generated by either melting or a combination of melting and evaporation, with submicron depth control of the hologram's individual pixels.

The shape and geometry of the hologram pixels are important because they affect the optical performance of the holographic structure. To obtain the maximum efficiency (contrast) of the diffractive image produced by the hologram, the pixels must have a certain depth and, ideally, a flat optically smooth base.

The research was funded by the ESPRC.

Source: Heriot-Watt University

REFERENCE:

1. Krystian L. Wlodarczyk et al., Journal of Materials Processing Technology (2016); doi:10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2015.03.001

John Wallace | Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.