Sub-terahertz imaging method from MIT improves autonomous vehicle vision

Autonomous vehicles relying on light-based image sensors often struggle to see through blinding conditions, such as fog. But Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT; Cambridge, MA) researchers have developed a sub-terahertz-radiation receiving system that could help steer driverless cars when traditional lidar methods fail.

Sub-terahertz wavelengths, which are between microwave and infrared radiation on the electromagnetic spectrum, can be detected through fog and dust clouds with ease, whereas the infrared-based lidar imaging systems used in autonomous vehicles struggle. To detect objects, a sub-terahertz imaging system sends an initial signal through a transmitter; a receiver then measures the absorption and reflection of the rebounding sub-terahertz wavelengths. That sends a signal to a processor that recreates an image of the object.

But implementing sub-terahertz sensors into driverless cars is challenging. Sensitive, accurate object-recognition requires a strong output baseband signal from receiver to processor. Traditional systems, made of discrete components that produce such signals, are large and expensive. Smaller, on-chip sensor arrays exist, but they produce weak signals.

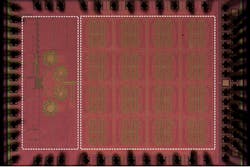

In a paper published by the IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits, the researchers describe a 2D, sub-terahertz receiving array on a chip that is orders of magnitude more sensitive, meaning it can better capture and interpret sub-terahertz wavelengths in the presence of a lot of signal noise.

To achieve this, they implemented a scheme of independent signal-mixing pixels--called heterodyne detectors--that are usually very difficult to densely integrate into chips. The researchers drastically shrank the size of the heterodyne detectors so that many of them can fit into a chip. The trick was to create a compact, multipurpose component that can simultaneously down-mix input signals, synchronize the pixel array, and produce strong output baseband signals.

The researchers built a prototype, which has a 32-pixel array integrated on a 1.2-square-millimeter device. The pixels are approximately 4300 times more sensitive than the pixels in today's best on-chip sub-terahertz array sensors. With a little more development, the chip could potentially be used in driverless cars and autonomous robots.

"A big motivation for this work is having better ‘electric eyes’ for autonomous vehicles and drones," says co-author Ruonan Han, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science, and director of the Terahertz Integrated Electronics Group in the MIT Microsystems Technology Laboratories (MTL). "Our low-cost, on-chip sub-terahertz sensors will play a complementary role to LiDAR for when the environment is rough."

The key to the design is what the researchers call "decentralization." In this design, a single pixel generates the frequency beat (the frequency difference between two incoming sub-terahertz signals) and the local oscillation--an electrical signal that changes the frequency of an input frequency. This "down-mixing" process produces a signal in the megahertz range that can be easily interpreted by a baseband processor.

The output signal can be used to calculate the distance of objects, similar to how lidar calculates the time it takes a laser to hit an object and rebound. In addition, combining the output signals of an array of pixels, and steering the pixels in a certain direction, can enable high-resolution images of a scene. This allows for not only the detection but also the recognition of objects, which is critical in autonomous vehicles and robots.

The researchers' decentralized design tackles the scale-sensitivity tradeoff. Each pixel generates its own local oscillation signal, used for receiving and down-mixing the incoming signal. In addition, an integrated coupler synchronizes its local oscillation signal with that of its neighbor. This gives each pixel more output power, since the local oscillation signal does not flow from a global hub.

For the system to gauge an object's distance, the frequency of the local oscillation signal must be stable. To that end, the researchers incorporated into their chip a component called a phase-locked loop that locks the sub-terahertz frequency of all 32 local oscillation signals to a stable, low-frequency reference. Because the pixels are coupled, their local oscillation signals all share identical, high-stability phase and frequency. This ensures that meaningful information can be extracted from the output baseband signals. This entire architecture minimizes signal loss and maximizes control.

SOURCE: MIT; http://news.mit.edu/2019/giving-keener-electric-eyesight-autonomous-vehicles-0214

Gail Overton | Senior Editor (2004-2020)

Gail has more than 30 years of engineering, marketing, product management, and editorial experience in the photonics and optical communications industry. Before joining the staff at Laser Focus World in 2004, she held many product management and product marketing roles in the fiber-optics industry, most notably at Hughes (El Segundo, CA), GTE Labs (Waltham, MA), Corning (Corning, NY), Photon Kinetics (Beaverton, OR), and Newport Corporation (Irvine, CA). During her marketing career, Gail published articles in WDM Solutions and Sensors magazine and traveled internationally to conduct product and sales training. Gail received her BS degree in physics, with an emphasis in optics, from San Diego State University in San Diego, CA in May 1986.