Photonics powers precision for next wave of life sciences

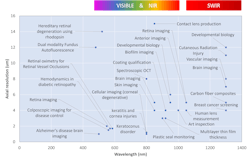

Advances in life science are progressing in applications as diverse as medical imaging, therapeutics, and analytics. A common thread links these frontiers: A marked increase in precision fueled by photonics.

Emerging advances such as the ability to visualize subcellular dynamics, guide surgical instruments with micron-level accuracy, or analyze vascular pathologies in real time are unfolding across vastly different clinical and research domains. They all share a common foundation: Advances in photonic components and systems are enabling life science researchers and medical professionals to manipulate, transmit, and detect light with unprecedented control.

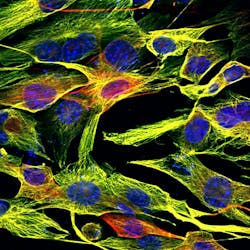

Life sciences stand to benefit as photonics suppliers continue to sharpen wavelength selectivity, energy efficiency, and signal integrity. Today, fluorescence microscopy, flow cytometry, robotic-guided laser surgery, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) exemplify photonic-enabled precision.

Fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry: An information density challenge

The drive toward multiparametric analysis has fundamentally changed the performance envelope for wavelength manipulation technologies. Early flow cytometry systems could simultaneously distinguish two or three cell populations, but researchers now routinely deploy panels that can detect more than 20 parameters—and the trajectory of recent developments points toward 40+ parameter systems. This increasing information density from multiparametric flow cytometry systems creates a cascade of photonic challenges: More fluorophores require tighter spectral spacing, which demands sharper wavelength selectivity and the need for faster switching between detection channels.

Although generating the excitation light is not trivial, laser sources have kept pace with these demands. The challenge is everything that happens afterward, including deflecting the beams to precise spatial positions, modulating intensity with microsecond response times, and filtering detection paths to isolate signals within an increasingly crowded spectral space.

Acousto-optic devices enable dynamic beam control without mechanical motion. In spatial flow cytometry, for example, acousto-optic deflectors allow separate multiple interrogation points along a sample’s flow stream. This effectively creates parallel analysis channels from a single laser source, which enables higher throughput without sacrificing measurement precision.

Tunable filters present similar challenges. As researchers pack more fluorophores into single assays, spectral unmixing becomes critical for accuracy. The ability to rapidly tune detection wavelengths while maintaining sharp spectral edges determines how well the closely spaced emission peaks can be resolved. Access to specific wavelength bands depends on the optical properties of acousto-optic crystals and filter substrates. This makes vertical integration of materials supply chains a powerful advantage because it allows a manufacturer to control crystal quality and optical characteristics to create devices that operate at wavelengths matched to emerging fluorophore chemistries.

These wavelength manipulation capabilities range from acousto-optic beam control to spectrally precise tunable filters and enable applications such as high-content screening—in which pharmaceutical researchers extract multiple readouts from single cells—as well as clinical diagnostics, where rare cell detection requires high specificity and high throughput. Wavelength control, not biology, defines how many parameters researchers can reliably multiplex.

Lasers + robotics = Precision surgery

Surgical precision for a growing number of medical procedures increasingly depends on how quickly and accurately photonic components can translate surgeon intent into robotic action. Whether guiding ablation beams through corneal tissue or providing optical tools for robotic positioning, photonic systems must operate with clinical-grade reliability.

The eye is an extremely sensitive and delicate organ with complex millimeter and sub-millimeter features and interfaces. Success of eye procedures depend on creating a precise laser beam that must be steered with micron-level accuracy—whether part of therapeutic surgery (treating post cataract) or as a preventive tool to detect underlying eye conditions. Acousto-optic deflectors enable precision by translating digital control signals into physical beam positioning faster and more repeatably than mechanical galvanometers can. These component technologies enable millions of annual procedures with predictably positive outcomes.

Robotic surgical platforms represent a more complex integration challenge. These systems combine multi-arm coordination, tremor reduction, and enhanced visualization to enable smaller incisions, reduced blood loss, and faster patient recovery. The photonic infrastructure supporting robotic surgery includes advanced fiber optics for endoscopy, imaging, and illumination. While specific implementations remain proprietary, the underlying principle is clear: Robotic precision requires low-latency optical feedback to coordinate motion across multiple degrees of freedom.

Robotic surgery platforms have moved from specialized academic centers to widespread clinical deployment, driven by improvements in accuracy and reduced complication rates. As these systems evolve, real-time micron-scale positioning will demand extremely low latency feedback controls, while vision-guided systems will require higher bandwidth. And the clinical environment demands reliability that won’t degrade over thousands of cycles.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) with surgical vision systems promises to further amplify these capabilities. Photonic sensors will be able to feed data into algorithms that can assist with navigation, identify anatomical structures, or even provide decision support.

OCT: Beyond ophthalmology

OCT enables cardiologists to assess stent deployment quality and vessel wall characteristics with micron-scale resolution within the artery itself. This level of detail, impossible with conventional angiography, depends on fiber-optic couplers to deliver both the bandwidth for deep tissue penetration and the spectral flatness required to maintain consistent resolution throughout the vessel wall.

In fact, OCT offers one of the clearest examples of the way component-level advances translate directly into new clinical capabilities. Although advances in detector sensitivity and computational power are driving OCT’s evolution from ophthalmology to cardiology to gastroenterology, fiber-optic couplers and laser diodes are equally critical.

It’s the standard of care for retinal disease diagnosis because OCT provides micron-scale cross-sectional images that enable early detection of pathological changes before they impact vision. And OCT is branching out into new anatomical territories where cross-sectional imaging provides clinical insights impossible with surface-only techniques.

Interventional cardiology represents the most technically demanding expansion of OCT, because systems must image arterial walls from inside narrow catheter lumens. The procedure uses a rotating optical probe that withdraws through the artery. Images are acquired at rates fast enough to capture vessel topology before blood flow obscures the view. It enables capabilities beyond conventional angiography, such as the assessment of stent placement and vessel wall composition, as well as the identification of plaque type.

The technique requires both adequate resolution and sufficient penetration depth, making two component parameters particularly important: fiber coupler bandwidth and spectral flatness. Broader coupler bandwidth enables deeper tissue penetration for imaging vessel walls several millimeters thick, while spectral flatness ensures axial resolution remains consistent across the imaging depth.

It’s clinically important that these photonic parameters directly determine diagnostic capability. A coupler with insufficient bandwidth limits how deeply a cardiologist can image into vessel walls. Spectral nonuniformity degrades resolution at the exact depths where pathology often resides. Component performance isn’t just a technical specification—it’s a clinical constraint.

The multipliers: Quantum sensing and AI

Two emerging technologies promise to amplify the impact of photonics further—at the component level and the system level.

Quantum sensing represents a new frontier in measurement sensitivity. Fiber-coupled acousto-optic modulators combined with fiber-coupled collimators enable the precise laser controls required for atom trapping and cooling. These two techniques can achieve sensitivities orders of magnitude beyond conventional optical sensors. While applications in atomic clocks and precision navigation are established, biosensing implementations remain in development. The question is how rapidly these quantum measurement capabilities can translate into clinical tools for detecting biomarkers, imaging neural activity, or characterizing tissue at molecular scales.

AI’s role as an amplifier takes a different form. It enables life science users to extract more value from data photonic systems already capture. In mammography, for example, AI algorithms can now analyze optically captured images to detect precancerous patterns radiologists might miss. For cardiology, AI processes OCT spectroscopic data to assess plaque composition and mobility in real time to provide insights beyond visual interpretation. For surgical robotics, machine learning algorithms can assist navigation and support decisions based on machine vision data. The pattern is consistent across applications: Photonics provides high-quality measurement modality, while AI multiplies its clinical value.

The next generation of life science instrumentation will depend on continued advances in wavelength control, energy/power efficiency, and signal integrity. But as quantum sensing and AI mature from research tools to clinical deployment, the potential value photonic systems offer life science will only multiply. Precision isn’t just a feature of these systems—it’s the foundation upon which they are built.

About the Author

Stratos Kehayas

Stratos Kehayas, Ph.D., is president of G&H Group’s Photonics Division (Fremont, CA).