FLUORESCENCE IMAGING: Probe permanently marks neurons engaged during specific activity

A new fluorescent protein lets scientists shine a light on an animal's brain to permanently mark neurons that are active at a particular time.1 Called CaMPARI (calcium-modulated photoactivatable ratiometric integrator), it converts from green to red when calcium floods a nerve cell after the cell fires. The permanent mark frees scientists from the need to focus a microscope on the right cells at the right time to observe neuronal activity.

Calcium-sensitive fluorescent molecules called GCaMP can indicate neural activity, and are useful for following the dynamics of neural networks. But their signal is temporary, and if researchers miss it because the microscope is not focused on the right spot, the information is lost. Developed at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute's Janelia Research Campus, CaMPARI enables visualization beyond a microscope's field of view, capturing neural activity across wide swaths of brain tissue. And in many cases it can be used while animals move freely, rather than being confined to a dish or embedded in agar. "The most enabling thing about this technology may be that you don't have to have your organism under a microscope during your experiment," says Loren Looger, a group leader and protein chemist at Janelia.

Eric Schreiter, a senior scientist in Looger's lab, led the development of CaMPARI-working as part of Janelia's Genetically-Encoded Neuronal Indicator and Effector (GENIE) interdisciplinary project team. The team started with a protein called Eos, which fluoresces in green until exposed to violet light—at which point it permanently alters to fluoresce in red. "That conversion from green to red gives us a permanent signal," said Schreiter. "So we just needed a way to couple that conversion to the activity that's going on in the cell." To do that, the scientists incorporated a calcium-sensitive protein known as calmodulin, which makes the color change dependent on the burst of calcium that accompanies neural activity.

To find a useful protein that switches the color of its fluorescence only in the presence of both calcium and violet light, the researchers made and screened tens of thousands of subtly different proteins. "When we finally got one that photoconverted more with calcium than without it, we knew we had a tool. We just needed to make it better to get it to the point where another neuroscientist could sit down and use it," says Ben Fosque, a graduate student in the biochemistry and molecular biophysics program at the University of Chicago.

The use of violet light gives experimenters control over the time period during which neural activity is tracked. "Ideally, we can flip the light switch on while an animal is doing the behavior that we care about, then flip the switch off as soon as the animal stops doing the behavior," Schreiter explains. "Then, we're capturing a snapshot of only the activity that occurs while the animal is doing that behavior."

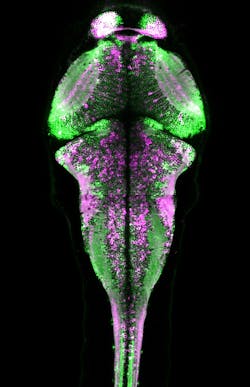

Various experiments have demonstrated CaMPARI's effectiveness. For instance, the researchers captured a snapshot of neuronal activity over the entire brain volume of a zebrafish during a 10-second period as it swam in a dish. Following the experiment, CaMPARI was red in motor neurons known to be involved in swimming, and other expected sets of neurons—consistent with observations made by other scientists during electrophysiology experiments. The activation patterns changed significantly when the researchers altered the temperature or turbulence of the water.

The scientists expect future versions of CaMPARI will be more sensitive and reliable, but "the idea is probably more powerful than the tool, as it stands right now," Looger says. To get it into the hands of other labs, the team has made the genetic plasmid encoding CaMPARI available through the plasmid repository Addgene, transgenic flies expressing CaMPARI are available through the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, and Janelia group leader Misha Ahrens is distributing CaMPARI-expressing zebrafish to researchers. Tools for introducing CaMPARI into mouse cells should be available soon, they say.

1. B. F. Fosque et al., Science, 347, 6223, 755–760 (2015).

About the Author

Barbara Gefvert

Editor-in-Chief, BioOptics World (2008-2020)

Barbara G. Gefvert has been a science and technology editor and writer since 1987, and served as editor in chief on multiple publications, including Sensors magazine for nearly a decade.