OPHTHALMOLOGY/MICROSCOPY/OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY: Novel ophthalmic imaging with adaptive optics, confocal imaging, and OCT

The human eye is complex and powerful, but extremely vulnerable—far more susceptible than any other organ to ailments via blunt force, bacterial infection, and exposure. While researchers have developed numerous innovations for the detection and treatment of these conditions, there is still plenty of opportunity to enhance ophthalmic diagnostic and treatment capabilities. The power of light may be the greatest contributor to this branch of medicine.

Unprecedented detail

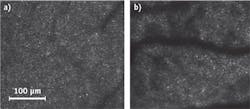

For the first time in history, rod photoreceptors were recently observed in the living human eye.1 (As you may recall from science class, rods work in conjunction with cones to transduce light into electrical signals, and they play the lead role in distinguishing depth and pigments.) Researchers at the University of Rochester achieved this remarkable feat with a powerful technology known as adaptive optics (AO; see table). Cone photoreceptors are more visible, with an image similar to a starry night, and provide a significant amount of diagnostic information (see Fig. 1).AO promises to provide value to life sciences applications by combining with confocal microscopy/imaging and optical coherence tomography (OCT). These three technologies have been heavily explored individually, but together they will provide novel and powerful synergy in clinical settings. As the trio evolves into an influential ophthalmology system, physicians will be able to clearly image the human eye down to individual rods or cones, and perhaps devise extremely accurate diagnostic procedures along with improved analysis of responses to treatments. The ultimate goal is to reduce the number of those affected by serious ailments such as macular degeneration, glaucoma, and ultimately blindness.

Adaptive optics plus OCT

AO technology is primarily used for long-range imaging such as astronomy, and for laser communication. The basic idea is that AO corrects for aberrations induced by atmospheric turbulence or for optical aberrations. An advanced detector, often a wavefront sensor, plots abnormalities and a deformable mirror—either membrane- or actuator-based—compensates where required (see Fig. 2). By itself, AO is not very practical, and so is often coupled with other techniques commonly used in biological imaging.OCT, one of the best known technologies applied to ophthalmology, typically uses low-coherence light sources. The properties of light—especially the wavelength—are critical in defining the region of the eye under inspection.

Used primarily to capture micrometric-resolution 3D images of eye tissue, ophthalmic OCT platforms are helpful for diagnostics. The technology works extremely well in processing depth-resolved retinal images, which are used to quantify the nerve fiber layers typically affected by glaucoma and other ailments.

Since one of the biggest problems with ophthalmic OCT is the aberrations induced by the curvature of the eye, AO has much to offer this application. Researchers in Japan have investigated AO OCT systems and compared them to non-AO spectral-domain OCT systems for field of view, lateral and axial resolution, overall sensitivity, and speed. In a non-AO system, the field of view is significantly reduced, whereas an AO-enhanced OCT system improves lateral resolution by a factor of 10. The two technologies provide nearly identical sensitivity and acquisition speed so where lateral resolution is critical for imaging analysis, it is recommended to combine AO with OCT. Simply put, the AO-OCT combination is advantageous when high contrast and high resolution are required, and when looking at the retina, specifically the nerve fiber layer, the overall structure of the fiber is acquired in addition to the thickness.2

Plus confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy is an older technology, but still extremely useful today for biological applications involving fluorescence and/or live tissue. As with OCT, when applied to bioimaging, confocal microscopy suffers because of the aberrations induced by biological tissue: Resolution and optical sectioning are dramatically affected internally by the system or externally by the specimen under inspection. This severely limits the ability of photons to reach the detector, and ultimately yields lower contrast and decreased throughput. In fact, aberration-free confocal imaging is a rarity, and improvement could make it much more useful.

Researchers in the United Kingdom have developed a confocal microscope and adapted it using AO to improve resolution and 3D rendering/reconstruction of the eye.3

From the cornea to the pupil, retina, and macula, depth and resolution depend on the region of interest. AO systems, deformable mirrors, and algorithm models can be adapted to improve the current pitfalls and create an adaptive confocal fluorescence microscope with reduced aberrations, improved contrast, and higher axial resolution.

Implementation and future development

There are both benefits and drawbacks to the merger of these technologies. The benefits are straightforward. AO on a confocal OCT platform allows for deeper tissue imaging with improved contrast and resolution to overcome aberrations that increase as light propagates further into the specimen. Specifically, lateral resolution is improved by a factor of 10, without sacrificing axial resolution, sensitivity, or data acquisition speed.

However, the drawbacks are very clear, simple, and understandable. First, adding AO to an imaging system dramatically raises cost, as AO systems typically exceed $15,000. The system footprint would also increase as the AO setup is adapted to augment confocal OCT, a system that has a relatively large footprint of its own. In addition, handling and expertise is required, as AO systems are sensitive and require time for setup and testing. Additional time would also be needed for data capture and analysis, as various algorithms are embedded to interpolate and process data.

But the drawbacks are already being addressed. Recently, for instance, researchers have developed sensorless techniques to reduce the price and the complexity of AO for both OCT and microscopy.4,5 These methods rely on the application of a metric to assess image quality, which acts as feedback for the image optimization. Special deformable mirrors that can directly generate low-order aberrations are very promising for these procedures.4

AO is currently being combined in a single platform with either OCT or confocal imaging. For example, the Department of Engineering at the University of Oxford in England is applying AO to aberration correction in a confocal microscope, and researchers in Japan are utilizing novel techniques with 1 μm AO in an OCT system. Both approaches result in higher resolution retinal imaging and higher penetration choroidal imaging, in addition to improvement of the overall signal-to-noise ratio that is often evident, as in the hazy outer layer of the eye.

Incorporating AO with OCT and confocal microscopy will allow the highest resolution and contrast, eliminating the effects of aberrations typically seen in a basic OCT or confocal system. Further investigation of photoreceptors will be achieved at the retina, which should yield improvements in the detection of ailments, treatment of diseases, and overall recovery.

REFERENCES

1. A. Dubra et al., Biomed. Opt. Exp., 2, 7 (2011).

2. K. Kurokawa et al., Opt. Exp., 18, 8, 8515–8527 (2010); retrieved from http://bit.ly/S65sAr.

3. M. J. Booth et al., Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 9, 5788–5792 (2002); retrieved from http://bit.ly/U4fkXw.

4. S. Bonora, Opt. Comm., 284, 13, 0030–4018 (2011).

5. D. Debarre, M. J. Booth, and T. Wilson, Opt. Exp., 15, 13, 8176–8190 (2007).

Stephan Briggs | Biomedical Product Line Engineer, Edmund Optics

Stephan Briggs started with Edmund Optics as an intern while pursuing his degree in biomedical engineering at Drexel University with a concentration on tissue engineering and biomaterials. Following graduation, he joined as Biomedical Engineer, working directly with EO’s life sciences customers. With a solid understanding of processes and technologies, he helps researchers and system builders accomplish their goals with correct application and integration of components and subsystems. He has authored numerous articles on a range of topics of interest to life scientists, including light sources, optics, individual and combined imaging approaches, and cost-efficient design options.