OPHTHALMOLOGY/MEDICAL IMAGING: Retinal imaging advances research, disease diagnosis

The organ we most depend on for providing input about our environment—the eye—is helpful for the diagnosis of diseases such as diabetes. Also, because the retina is part of the brain, its assessment enables identification of neurological effects–and thus the eye warrants significant research attention.

A number of technology advances are fueling progress in retinal imaging—both for research and clinical application.

In vivo research

Mice have played a key role for research into biological functions such as vision, and are especially attractive for genetic research because they have a particularly "plastic" genome. They can be genetically engineered to have various diseases that mimic human dystrophies such as diabetes and Alzheimer's disease.

"A barrier to effective animal research has been the difficulty of imaging the retina in these tiny mammals," says Bert Massie of Phoenix Research Laboratories (Pleasanton, CA; www.phoenixreslabs.com), explaining that the mouse eye, at 3 mm in diameter, is a fraction of the size of the 25-mm human eye. "Attempts to use cameras designed for the human eye have produced limited results and at great expense," he notes.

Addressing the great need for retinal imaging specifically in small animal research, Phoenix Research Labs provides instrumentation that incorporates multiple imaging modalities important for eye research. These include white light (also called brightfield) imaging; angiography, in which injected fluorescein enables retinal blood flow study; and imaging of fluorescent probes such as green fluorescent protein (GFP) where the challenge is to observe a low level of fluorescent return. When Phoenix Research Laboratories developed its Micron III retinal imaging microscope specifically for laboratory rodents, a key design objective was to deliver these imaging modalities—along with a wide field of view; resolutions below 5 µm; and easy, rapid imaging (a mouse or rat can be imaged by a solo technician in less than a minute). (See Fig. 1.)

Key to achieving these design objectives is the system's CCD camera. Massie explains that a standard, single-chip CCD camera could not deliver the performance needed because it uses a mask over the pixels with an array of filters to capture a color image. Since most of the spatial information is in the green, the pattern of filters provides twice the number of green samples as red or blue, and the software interpolates the colors where measurements are not made. By contrast, a three-chip CCD uses a prism to separate the colors, each of which is then sent to one of three CCDs. This allows equal spatial resolutions for each color, for good color images and for fluorescent studies at arbitrary wavelengths. The Micron III uses Toshiba Imaging's (Irvine, CA; cameras.toshiba.com) 56 × 44 × 44 mm IK-TF7 three-chip CCD camera to provide high resolution (XGA) and a full pixel-independent readout of 30 frames per second and 1000 to 1 dynamic range. Important to live animal retinal imaging tasks, three 1/3-in. progressive scan CCDs eliminate image jitter.

Another key to improved research is the ability to perform in vivo imaging of the mice. Traditionally, researchers must breed large colonies of animals, sacrifice a segment of the colony at each stage of disease progress, and then remove the retina and flat-mount it to a microscope slide for examination. The process is complicated, and precludes longitudinal studies. The Micron III addresses this need as well.

The results are providing new insights into the eye. A typical set of images demonstrates the system use in a variety of observational modalities, from bright field to fluorescein angiography to GFP (see Fig. 2). New attachments are in development for imaging the anterior segment and for performing visual function tests.Research to clinical

Imagine Eyes (Orsay, France, www.imagine-eyes.com), developer of the compact adaptive optics retinal camera prototype described in the article, "Adaptive optics approaches clinical ophthalmology," https://bit.ly/AdaptiveOptics), says it expects to launch its second-generation system this Fall.

The system's first generation had a prototype interface and a 4 × 4° field of view at ±2–3 µm. The goals of the second generation are a more ergonomic interface, a wider imaging field and better image contrast. It is geared to enable clinical and academic users with minimal training to capture and stitch together component images to form large, wide-field views. "This second generation will be a crucial step in launching a commercial camera as quickly as possible," says Mark Zacharria, director of marketing communications at Imagine Eyes.

Meanwhile, the company will provide component technologies to basic research as well as systems to academic and industrial users.

Clinical functional imaging

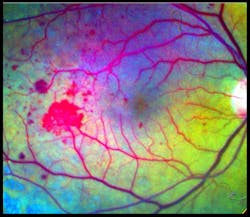

Speaking at the BiOS Hot Topics session during Photonics West 2010, Professor Amiram Grinvald, founder and CEO of Optical Imaging Ltd. (www.opt-imaging.com) and a faculty member of the Weizmann Institute of Science (Rehovot, Israel), described the application of his company's Retinal Function Imager (RFI), an FDA-approved hardware-and-software system providing noninvasive, ophthalmic functional imaging—in < 1 s to 10 min—to the resolution of single red blood cells moving through capillaries. 1 The system is partially based on a technique described in Grinvald's 1986 paper in Nature for functional imaging of the brain based on intrinsic signals. 2 Alternative technologies, such as PET and f-MRI, still provide only 1–10% of the resolving power of Grinvald's approach in both the temporal and the spatial domains, he says.RFI enables direct visualization of retinal blood dynamics without the injection of contrast agents, and clearly reveals the motion of individual red blood cells and blood cell clusters, thus enabling quantitative detection of abnormal blood flow velocity in capillaries, arterioles, and venules (see Fig. 3). This opens the door to many new diagnostic possibilities—for instance, a significant velocity decrease in arteries and veins may indicate non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. And increased blood flow velocity in the retinal arteries and veins can be an early indicator of diabetes mellitus in patients without any sign of diabetic retinopathy.

The basic RFI 3000 offers both blood flow velocity mapping and capillary perfusion mapping (CPM), which enables analysis of a series of images to reveal motion and microvasculature detail—often in greater detail than the gold standard for clinical retinal imaging: fluorescein angiography (FA; see Fig. 4).The higher-end RFI 3006 adds a multispectral imaging and analysis module, for instance, to provide insight into oxygen use and other functions. Based on a fast-switching filter wheel, it overcomes issues such as poor signal-to-noise ratio that have typically hampered such analyses. The module enables assessment of the oximetric state of the retina and visualization of choroidal vessels. This latter option provides ICG-like images (using the contrast agent IndoCyanine-Green) without the use of ICG.

Retinal reflectance changes in response to photic stimulation carry information about metabolic processes—which is the basis for the 3006's metabolic functional imaging capability. RFI can image under near-IR light, outside the absorption range of the photoreceptors, and thus can be used to optically monitor retinal activity in response to a well-defined visual stimulus. The metabolic state of retinal components is determined by comparing post and pre-stimulated images, reflecting changes in absorption outside the absorption range of the photoreceptors or scattering. It has been found in animal model experiments that the functional signal is very sensitive for the detection of induced glaucoma.

The system features a 12.3-mm square sensor with resolution of 1024 × 1024 pixels that capture images at 60 Hz. Its light source is a stroboscopic xenon with eight flashes at 100-Hz maximum frequency and a 10-s inter-series recharging interval. Imaging optics include a Topcon TRC-50DX fundus camera with three-position variable field angle. Software modules enable capture, sophisticated analysis, storage and retrieval, image processing, and display of related imagery as well as relevant historical and clinical information.

References

- D. Izhacky et al., Jpn. J. Ophthalmol., 53(4):345–51, July 2009.

- A. Grinvald et al., Nature, 1986, 324: 361–364.

About the Author

Barbara Gefvert

Editor-in-Chief, BioOptics World (2008-2020)

Barbara G. Gefvert has been a science and technology editor and writer since 1987, and served as editor in chief on multiple publications, including Sensors magazine for nearly a decade.