Modified fluorescence microscope can view spectrum from specific structures within samples

Researchers at the University of Chicago (Illinois) have converted a standard wide-field inverted fluorescence microscope into a spatially selective, spectrally resolved tool, allowing users to zero in on the spectrum from specific structures within a sample. The goal of the research team's work is to enable observation of the spectrum of light that comes from part of a sample on a microscope, but not the entire sample.

Related: Facilitating fluorescence with optical filtering

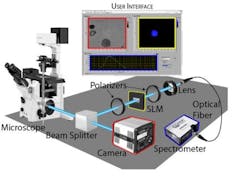

The retooled fluorescence microscope works by splitting the light that comes from a sample, with half going to a camera for normal imaging and the other half going to a spectrometer. But before it gets to the spectrometer, that half passes through a few optical components that allow users to choose any arbitrary portion of the image and block everything else out.

"There’s nothing tricky about these optical components--a spatial light modulator (SLM) between crossed polarizers," explains Adam Hammond, curriculum director and senior lecturer in the Biophysical Sciences program at the Gordon Center for Integrative Sciences at the University of Chicago. "SLMs are common now, with at least three in many modern digital projectors. They have an array of pixels that can each manipulate the phase of the light that passes through them."

The modified microscope's simple concepts and components can easily be adapted for many different purposes, and added to existing microscopes easily and inexpensively. Importantly, Hammond says, it can take the full spectrum of one or more user-defined regions of interest while simultaneously capturing standard fluorescence images of the whole field of view. The research team is using it now to follow fluorescent probes for pH and calcium, but Hammond says it could also have the ability to identify individual microorganisms within a mixed sample by their absorbance fingerprint.

"By using a pulsed excitation source, the fluorescence lifetime of a probe could be measured from a select region of interest," Hammond says. "One interesting potential application is within the field of neuroscience for resolving single action potentials with dyes that are sensitive to membrane potential. Fluorescence lifetime measurements provide an advantage over direct fluorescence measurements because they're independent of the concentration of the probe."

Full details of the work appear in the Review of Scientific Instruments; for more information, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4967274.