Fluorescence method detects metabolic changes linked to multiple diseases

Recognizing that metabolic changes in cells can occur at the earliest stages of disease, researchers at the Tufts University School of Engineering (Medford, MA) have developed an optical tool that can read metabolism at subcellular resolution, without having to perturb cells with contrast agents or destroy them to conduct assays. The researchers were able to use the method to identify specific metabolic signatures that could arise in diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases.

Related: Multiphoton microscopy detects skin cancers noninvasively

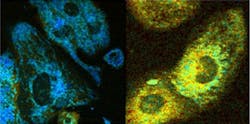

The method is based on the fluorescence of two important coenzymes (biomolecules that work in concert with enzymes) when excited by a laser beam. The coenzymes—nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD)—are involved in a large number of metabolic pathways in every cell. To find out the specific metabolic pathways affected by disease or stress, the research team looked at three parameters: the ratio of FAD to NADH, the fluorescence "fade" of NADH, and the organization of the mitochondria as revealed by the spatial distribution of NADH within a cell.

The first parameter—the relative amounts of FAD to NADH—can reveal how well the cell is consuming oxygen, metabolizing sugars, or producing or breaking down fat molecules. The second parameter—the fluorescence "fade" of NADH—reveals details about the local environment of the NADH. The third parameter—the spatial distribution of NADH in the cells—shows how the mitochondria split and fuse in response to cellular growth and stress.

"Taken together, these three parameters begin to provide more specific, and unique metabolic signatures of cellular health or dysfunction," explains Irene Georgakoudi, a professor in the Department of Department of Biomedical Engineering, who led the work. "The power of this method is the ability to get the information on live cells, without the use of contrast agents or attached labels that could interfere with results."

Other methods exist for noninvasively tracking the metabolic signatures of disease, such as the positron emission tomography (PET) scan, which is often used in research. But while PET scans provide low-resolution information with excellent depth penetration into living tissues, the optical method introduced by the Tufts researchers detects metabolic activity at the resolution of single cells, although mostly near the surface.

Many diseases can be detected at the surface of tissues, including cancer, while many preclinical studies are performed with animal models and engineered three-dimensional tissues that can benefit from being monitored nondestructively. The method developed by Georgakoudi and colleagues may prove to be a powerful research tool for understanding their metabolic signatures.

Full details of the work appear in the journal Science Advances.