Fluorescence imaging method can detect tuberculosis infection in an hour

A team of researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine (Stanford, CA) has developed a two-piece fluorescent probe that is activated when it comes in contact with tuberculosis (TB) bacteria in phlegm. The technique can diagnose live TB in an hour and help monitor the efficacy of treatments.

Jianghong Rao, Ph.D., a professor of radiology at the School of Medicine and the senior author of a paper describing the work, says that current methods for TB diagnosis can take up to two months to complete—a stretch during which infected individuals could spread the disease broadly, even if they don't know they are infected. A quicker diagnosis could curtail the infection rate. What's more, the new method is cheaper and easier to carry out, ideally enabling healthcare providers in poorer communities to one day adopt the technology.

To diagnose TB, clinicians need to collect a sample of sputum, cultivate it in the lab, and wait for the bacteria to grow to detectable level. It also requires specialized facilities, which are missing in many hospitals worldwide. The new imaging technique, however, uses conventional fluorescence microscopes that nearly all hospitals have and that require no special training, Rao says. All that is needed is a sample of the patient's sputum that can be prepared and put under the microscope for analysis.

Related: A breath screen for active tuberculosis at the point-of-care

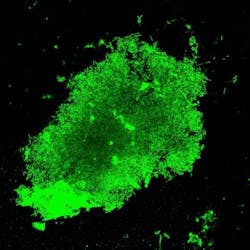

The tactic harnesses a newly created two-piece fluorescent probe, which is combined with the sputum sample and gets activated when it comes in contact with TB bacteria. One part of the probe is responsible for detecting live TB, thus creating the telltale glow, while the second part—a molecule that binds specifically to the TB microbe—localizes the glow to the bacterium. The concentrated fluorescence allows scientists to not only see the rod-shaped bacteria themselves, but also to track their distribution in infected host cells.

"For cases of drug-susceptible TB, the treatment success rates are at least 85%, but the rate of success is only 54% for multidrug-resistant TB, which requires longer treatments and more expensive, more toxic drugs," Rao says.

Researchers applied the fluorescent probe to a sputum sample collected from a tuberculosis-positive patient; the bright green shows where there is live tuberculosis. (Image credit: Jianghong Rao)

The fluorescent probe, Rao says, can help determine the appropriate drug by showing which bacteria are still alive in the patient sample: those that are alive glow green, while those that aren't (or are a different species of bacteria) appear dark.

Outside the clinic, Rao says the technique could help scientists developing new TB drugs figure out which drugs work best for each particular strain. Now, he and his colleagues are planning to test the probe and to work on obtaining approval from the U.S. FDA.

Full details of the work appear in the journal Science Translational Medicine.