Optogenetics shows that memories live in specific brain cells

Using optogenetics, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT; Cambridge, MA) sought to learn whether memory traces, known as memory engrams, are conceptual or if they are a physical network of neurons in the brain. Optogeneticsâa technique that uses low-level light to selectively activate proteins administered to live tissuesâenabled the researchers to show that memories reside in specific brain cells, and that activating a small fraction of brain cells can recall an entire memory.

The MIT team demonstrated that behavior based on high-level cognition, such as the expression of a specific memory, can be generated in a mammal by highly specific activation of a specific small subpopulation of brain cells using light, says Susumu Tonegawa, the Picower Professor of Biology and Neuroscience at MIT and lead author of the study.

"We wanted to artificially activate a memory without the usual required sensory experience, which provides experimental evidence that even ephemeral phenomena, such as personal memories, reside in the physical machinery of the brain," adds co-author Steve Ramirez, a graduate student in Tonegawaâs lab.

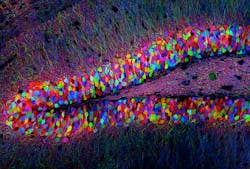

The researchers first identified a specific set of brain cells in the hippocampus that were active only when a mouse was learning about a new environment. They determined which genes were activated in those cells, and coupled them with the gene for channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2), a light-activated protein used in optogenetics.

Next, they studied mice with this genetic couplet in the cells of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, using tiny optical fibers to deliver pulses of light to the neurons. The light-activated protein would only be expressed in the neurons involved in experiential learningâallowing for labeling of the physical network of neurons associated with a specific memory engram for a specific experience.

Finally, the mice entered an environment and, after a few minutes of exploration, received a mild foot shock, learning to fear the particular environment in which the shock occurred. The brain cells activated during this fear conditioning became tagged with ChR2. Later, when exposed to triggering pulses of light in a completely different environment, the neurons involved in the fear memory switched onâand the mice quickly entered a defensive, immobile crouch.

This light-induced freezing suggested that the animals were actually recalling the memory of being shocked. The mice apparently perceived this replay of a fearful memoryâbut the memory was artificially reactivated. "Our results show that memories really do reside in very specific brain cells," says Liu, "and simply by reactivating these cells by physical means, such as light, an entire memory can be recalled."

The method may also have applications in the study of neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. "The more we know about the moving pieces that make up our brains," says Ramirez, "the better equipped we are to figure out what happens when brain pieces break down."

Other contributors to the team's work were Karl Deisseroth of Stanford University, whose lab developed optogenetics, and Petti T. Pang, Corey B. Puryear, and Arvind Govindarajan of the RIKEN-MIT Center for Neural Circuit Genetics at the Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT. The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the RIKEN Brain Science Institute.

For more information on the team's work, which appears in Nature, please visit http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v483/n7390/full/483397a.html#/access.

-----

Follow us on Twitter, 'like' us on Facebook, and join our group on LinkedIn

Follow OptoIQ on your iPhone; download the free app here.

Subscribe now to BioOptics World magazine; it's free!