Ultralight, low-cost OCT scanner screens for retinal diseases

Knowing that optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging is rarely included as part of a standard retinal screening exam since these systems can cost more than $100,000, a team of biomedical engineers at Duke University (Durham, NC) has developed a low-cost, portable OCT scanner for use by underserved regions in screening for retinal diseases such as macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma. The device features a redesigned, 3D-printed spectrometer to make it 15X lighter and smaller than current commercial systems, and is made from parts costing less than a tenth the retail price of commercial systems.

In its first clinical trial, the new OCT scanner produced images of 120 retinas that were 95% as sharp as those taken by current commercial systems, which was sufficient for accurate clinical diagnosis.OCT works by sending sound waves into tissues and measuring how long they take to come back. But because light is so much faster than sound, measuring time is more difficult. To time the light waves bouncing back from the tissue being scanned, OCT devices use a spectrometer to determine how much their phase has shifted compared to identical light waves that have traveled the same distance, but have not interacted with tissue.

The primary technology enabling the smaller, less-expensive OCT device is a new type of spectrometer designed by Adam Wax, professor of biomedical engineering at Duke, and his former graduate student Sanghoon Kim. Traditional spectrometers are made mostly of precisely cut metal components and direct light through a series of lenses, mirrors, and diffraction slits shaped like a W. While this setup provides a high degree of accuracy, slight mechanical shifts caused by bumps or even temperature changes can create misalignments.

Related: Advances in functional OCT

Wax's design, however, takes the light on a circular path within a housing made mostly from 3D-printed plastic. Because the spectrometer light path is circular, any expansions or contractions due to temperature changes occur symmetrically, balancing themselves out to keep the optical elements aligned. The device also uses a larger detector at the end of the light’s journey to make misalignments less likely.

Traditional OCT machines weigh more than 60 pounds, take up an entire desk, and cost anywhere between $50,000 and $120,000. The new OCT device weighs four pounds, is about the size of a lunch box and, Wax expects, will be sold for less than $15,000.

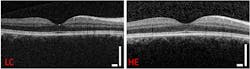

In the new study, J. Niklas Ulrich, retina surgeon and associate professor of ophthalmology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine (Chapel Hill, NC), put the new OCT scanner to the test against a commercial instrument produced by Heidelberg Engineering. He performed clinical imaging on both eyes of 60 patients, half from healthy volunteers and half with some sort of retinal disease.

To compare the images produced by both machines, the researchers used contrast-to-noise ratio—a measure often used to determine image quality in medical imaging. The results showed that, by this metric, the low-cost, portable OCT scanner provided useful contrast that was only 5.6% less than that of the commercial machine, which is still good enough to allow for clinical diagnostics.

Wax is commercializing the device through a startup company called Lumedica, which is already producing and selling first-generation instruments for research applications. The company hopes to secure venture backing in the near future and is also negotiating potential licensing deals with outside companies.

Full details of the work appear in the journal Translational Vision Science & Technology.