Moving surface-plasmon resonance into the infrared range enables measurement of drug penetration into living cells.

By Michael Golosovsky, Dan Davidov, Benjamin Aroeti

Even the simplest living cells are actually quite complex. Their ability to interact with other cells, and with biomolecules such as proteins and lipids, is evidence of this fact. Tracking these interactions in real time has traditionally involved labeling the biomolecules with fluorescent, radioactive, or chemical tags. But these tags can modify physiological activity of the cells, and so a major challenge in pharmacology and cell biology is to develop label-free techniques for monitoring dynamic interactions between biomolecules and living cells.

Surface-plasmon resonance (SPR) is a label-free optical technique that is widely used to study biorecognition processes1 (also see “Plasmons point out proteins”; www.bioopticsworld.com/articles/314097). The SPR technique measures optical reflection from the gold-coated sensor that is in contact with the biological medium. The incident optical wave impinges at the interface between the sensor and the biomedium at a specific angle that corresponds to the excitation of the surface electromagnetic wave which is named surface plasmon. The surface-plasmon penetration depth into biomedium is very low, in such a way that it effectively propagates in a thin layer adjacent to the metal-coated sensor. The optical reflectivity in the SPR regime is extremely sensitive to changes in thickness and refractive index of this thin layer.

Visible vs. IR

Conventional SPR machines typically operate in the visible and near-visible wavelength range, from 600 to 800 nm. Surface-plasmon waves in the visible range, characterized by shallow penetration of less than 200 nm, are useful for studying monomolecular layers that are in contact with the sensor’s surface. This is why SPR is popular for quantitative studies of dynamic interactions in thin biolayers, including molecular recognition or binding events. However, visible-range SPR is not optimal for studying living cells because the cells’ size considerably exceeds the penetration depth of visible-range surface-plasmon waves.

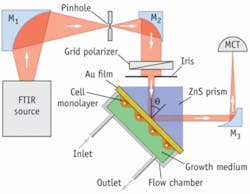

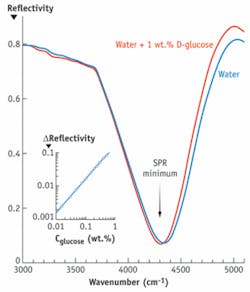

Infrared (IR) surface plasmons, on the other hand, penetrate much deeper and are more appropriate for studying cells. In particular, the penetration depth of mid-IR surface-plasmon waves is 1 to 10 µm and that is just about cell height. Recent efforts at the Hebrew University combined expertise in physics and in cell biology to develop a mid-IR SPR technique that uses a Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer as a light source (see Fig. 1). This technique is sensitive enough to measure physiological concentrations of glucose in water and in human plasma (from 3 to 20 mM; see Fig. 2). It allows real-time and label-free studies of lipid membranes and cells cultured on the gold-coated surface2, 3, particularly drug and protein penetration into cells. In principle, this SPR-FTIR technique also enables detection of biomolecules based on their spectral fingerprints, thus bridging traditional plasmonics with mid-IR spectroscopy.

Figure 2. D-glucose concentration in solution is measured by the infrared surface-plasmon resonance. Reflectivity minimum, corresponding to the excitation of the surface-plasmon resonance, is shifted to longer wavelengths upon increasing glucose concentration. This shift is used to quantify glucose concentration in solution.

null

Technique in action

Two examples illustrate how the FTIR-SPR technique can be used for studying living cells.

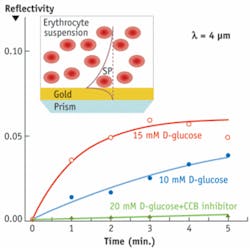

In the first example, we used mid-IR SPR to study glucose uptake by human red blood cells (see Fig. 3). The mid-IR surface plasmon had a large penetration depth, 4.5 μm, which is comparable to the diameter of a red blood cell. The SPR reflectivity increased when D-glucose began to penetrate into erythrocytes. The SPR reflectivity remained nearly constant when the cytochalasine B inhibitor, that prevents glucose uptake, was added.

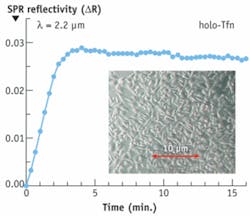

The second example involves sensing dynamic processes occurring in human melanoma cells upon introduction of holo-transferrin, a blood-plasma protein for iron ion delivery (see Fig. 4). The cells were cultured directly on gold and the IR surface plasmon with the penetration depth of 1.5 μm was used. This plasmon penetrates sufficiently deep into cells and clearly senses holo-Tfn penetration into the cells.

The FTIR-SPR offers a powerful methodology that can be applied for real-time and quantitative sensing of drug delivery into, and clearance from, living cells.

REFERENCES

- W. Knoll, Ann. Rev. Phys. Chem. 49, 569 (1998).

- R. Ziblat, V. Lirtsman, D. Davidov, and B. Aroeti, Biophys. J. 91, 776 (2006).

- V. Lirtsman, M. Golosovsky, D.Davidov, J. Appl. Phys. 103, 014702 (2008).

Michael Golosovsky and Dan Davidov are researchers at the Racah Institute of Physics, and Benjamin Aroeti is a researcher in the Silberman Institute of Life Sciences of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Giv’at Ram, Jerusalem 91904, Israel. Contact Dr. Golosovsky at [email protected].