Visible light plays role in designing safer component for drug development

When the aniline component of the pain-relieving drug acetaminophen breaks down in the liver, it can produce toxic metabolites. Recognizing this, researchers at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI) have developed a new component, using visible light in the process to drive chemical reactions, that can serve as a safer alternative for drug development.

The pharmaceutical industry commonly uses anilines as the basis for developing new drug therapies. But the way the liver metabolizes many drug therapies containing anilines can cause toxic side effects. For example, overloading the liver with acetaminophen can cause liver failure. Other drugs can trigger a harmful immune response in the body as a result of the unwanted metabolism.

"The problem with anilines is that they are readily metabolized by our liver, and that can create problems," explains Corey Stephenson, a professor of chemistry at the University of Michigan who led the work. "We want our drugs to be metabolized, but not in a way that causes them to have toxic effects."

Stephenson and his team's research into developing a safer building block began as a desire to explore ways to use visible light to drive chemical reactions. The team began looking into structures called aminocyclopropanes, hoping to convert them into more complex and more valuable compounds.

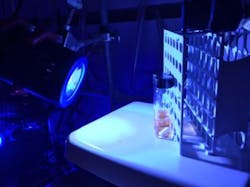

The Stephenson lab uses blue LEDs to activate their photocatalysts. (Image credit: The Stephenson Lab)

The team recognized the potential to convert aminocyclopropanes into a different compound, a 1-aminonorbornane, which is more complex and traditionally very difficult to synthesize. The research team also realized that these 1-aminonorbornanes could be highly useful in discovering new drug leads, as they do not seem to be metabolized in harmful ways by liver enzymes.

"We realized that we can use these aminonorbornane cores as a substitute for an aniline," said Daryl Staveness, a University of Michigan postdoctoral researcher and American Cancer Society fellow. "Usually, drug companies will need to re-engineer drugs that use it to avoid that oxidation event. But in using aminonorbornanes, we don't have to worry about those metabolic processing issues."

The process the team used to convert aminocyclopropanes into the beneficial 1-aminonorbornane structures has another benefit: because the reaction needed to produce the molecule is powered by visible light, 1-aminonorbornanes can be produced cheaply, sustainably, and on a large scale.

"Using traditional chemical approaches, 1-aminonorbornanes have been previously difficult to synthesize, requiring inefficient sequences of reactions and forcing inflexible conditions," says Taylor Sodano, study co-author and a University of Michigan graduate student. "Now, we can do it in one step at room temperature, using visible light and environmentally friendly conditions."

To produce 1-aminonorbornanes, the team employed a photocatalyst to execute the desired transformation. Catalysts are compounds that facilitate a chemical reaction, and in the case of photoredox catalysis, the special brand of photochemistry the team used, the catalysts operate by using the energy of visible light to shuttle electrons between molecules.

The University of Michigan research team's simple setup includes blue LED strips and a jacketed water bath to maintain a constant temperature over the course of the reaction. Once the aminocyclopropane and photocatalyst is added in solution to a vial, the team just turns on the lights and lets the photocatalyst do the work. (Image credit: The Stephenson Lab)

When Sodano and Staveness mix their photocatalyst with an aminocyclopropane and expose the solution to LED lights, the catalyst takes an electron from the aminocyclopropane, initiating the process that produces the 1-aminonorbornane, which is still missing its electron. The catalyst then gives the electron back to complete the reaction. Nothing else needs to be added other than the light, making this process exceptionally environmentally benign.

Study co-author Klarissa Jackson of Lipscomb University studied the safety of the 1-aminonorbornanes. She applied the compounds to liver fragments containing the enzymes that typically metabolize drug compounds. She found that when the enzymes broke down the 1-aminonorbornanes, the process did not produce the harmful metabolites that result from anilines.

Full details of the work appear in the journal Cell.