Polarized light imaging tool could reduce surgery-related injury and chronic pain

Researchers from the Academic Medical Center (AMC) at the University of Amsterdam (Netherlands) turned to a noninvasive imaging approach that uses polarized light to make nerves stand out from other tissue, which could help surgeons avoid accidentally injuring nerves or assist them in identifying nerves in need of repair.

Related: Optical Surgical Navigation group targets meaningful tool comparison

Although nerve injuries are a known complication for many types of surgery, surgeries involving the hand and wrist come with a higher risk because of the dense networks of nerves in this area. There are a few techniques available to help doctors identify nerves, but they have various limitations such as not providing real-time information, requiring physical contact with the nerve, or requiring the addition of a fluorescent dye.

"We have shown that nerves can be distinguished in human tissue by detecting the interaction of light with the structure of nerves without the need for fluorescent markers or physical interaction," says Kenneth Chin, a medical student at AMC. "Using an intraoperative, noninvasive real-time method minimizes potential nerve damage, which can result in fewer negative consequences such as reduced function, loss of sensation, or chronic pain."

Kenneth and his cousin Patrick Chin used an optical technique known as collimated polarized light imaging (CPLi) to identify nerves during surgery. Kenneth later joined a research group led by Thomas van Gulik, a surgeon at AMC, and brought along a working prototype, which has been further developed into a practical system that can be deployed in the operating room.

The researchers report that a surgeon using CPLi technology was able to correctly identify nerves in a human hand 100% of the time, compared to an accuracy rate of 77% for the surgeon who identified nerves using only a visual inspection.

CPLi uses a polarized beam of light to illuminate the tissue. When this light passes through a nerve, the tissue's unique internal structure reflects the light in a way that is dependent on how the nerve fiber is oriented compared to the orientation of the polarization of the light. By rotating the light's polarization, the reflection appears to switch on and off, making the nerve tissue stand out from other tissue. For this application, it was important to use light that was collimated, meaning all the light waves were parallel to each other, to maximize the amount of light reflected by the tissue.

"We adapted the optics used for CPLi so that they could be incorporated in a surgical microscope, which can be placed above the surgical area," Kenneth Chin says. "The resulting system can be used in a wide range of surgical fields where superficial nerves need to be identified."

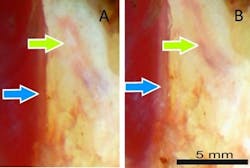

After testing their technique on animal tissue, the researchers used it to examine 13 tissue sites from the hand of a human cadaver. A surgeon looked for nerve tissue at these sites by eye under typical surgical illumination while a different surgeon used CPLi for an independent assessment. Histological evaluation was then used to verify the presence of nerve tissue at each site. The surgeon using visual inspection correctly identified nerve tissue in 10 of the 13 cases while the surgeon using CPLi correctly identified nerve tissue in all cases.

With patient consent, the researchers also used CPLi to successfully identify nerve tissue during a procedure to relieve pain in the wrist. They plan to do additional tests of the technique during live surgery to better understand how the optical reflection of nerves might vary among patients and under various surgical conditions.

"This technique could improve the effectiveness of surgical interventions by helping the surgeon identify nerves in the operative field," van Gulik says. "This leads to surgeons being more confident in their surgical procedure, which will lead to less accidental injury and more targeted surgical interventions."

Full details of the work appear in the journal Biomedical Optics Express.

BioOptics World Editors

We edited the content of this article, which was contributed by outside sources, to fit our style and substance requirements. (Editor’s Note: BioOptics World has folded as a brand and is now part of Laser Focus World, effective in 2022.)