Novel scanner hooks to a smartphone to detect viruses

Knowing that current methods to detect viruses and other biological markers of disease are effective, yet large and expensive (such as fluorescence microscopes), a team of researchers at the University of Tokyo (Tokyo, Japan) has developed and tested a miniaturized virus-scanning system that makes use of low-cost components and a smartphone. The researchers hope the system could aid those who tackle the spread of diseases faster, as current tools—while highly accurate at counting viruses—are too cumbersome for many situations, especially when rapid diagnosis is required.

The newly developed device, which scans biological samples for real viruses, is portable, low-cost, and battery-powered. Yoshihiro Minagawa from the University of Tokyo, who led the development, tested the device with viruses, but says it could also detect other biological markers."I wanted to produce a useful tool for inaccessible or less-affluent communities that can help in the fight against diseases such as influenza," says Minagawa. "Diagnosis is a critical factor of disease prevention. Our device paves the way for better access to essential diagnostic tools."

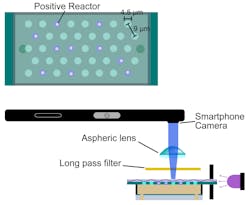

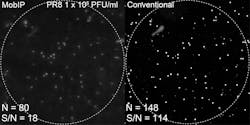

"Given two equal samples containing influenza, our system detected about 60% of the number of viruses as the fluorescence microscope. But it's much faster at doing so and more than adequate to produce good estimates for accurate diagnoses," continues Minagawa. "What's really amazing is that our device is about 100 times more sensitive than a commercial rapid influenza test kit, and it's not just limited to that kind of virus."The research team's device is about the size of a brick with a slot on top for placing a smartphone, enabling the smartphone's camera to look through a small lens to the inside of the device. On the screen through a custom smartphone app, an observer would see what may at first glance look like a starry night sky, except the "stars" are individual viruses.

Viruses are held in place on a clear surface in tiny cavities lit with an LED. The surface and fluid surrounding it were designed so that only when a cavity has a virus inside does incident light—the light that directly hits the surface—from the LED redirect up to the camera, manifesting in a bright pixel in an otherwise dark void. Each cavity is 48 femtoliters.

"This is now possible because smartphones and their embedded cameras have become sufficiently advanced and more affordable. I now hope to bring this technology to those who need it the most," concludes Minagawa. "We also wish to add other biomarkers such as nucleic acids—like DNA—to the options of things the device can detect. This way, we can maximize its usefulness to those on the front line of disease prevention, helping to save lives."

Full details of the work appear in the journal Lab on a Chip.