Deep Tissue Imaging/Neuroscience: Controlling scatter for high-speed, deep-tissue imaging

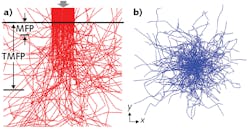

Tissue scattering degrades imaging by bending both excitation and emission light (see Fig. 1). Biological tissues, as inhomogeneous media, scatter light randomly,1 and in the context of strong backscattering, excitation light is limited in its ability to penetrate tissue. Even in situations involving less scattering, imaging performance is degraded by distorted focus and crosstalk. For this reason, many strategies have been proposed to address scattering. The ultimate goal, for neuroscientists, is generation of high-quality images at high speed, deep in the brain.

Lingjie Kong’s lab at Tsinghua University (Beijing, China) is responsible for a number of novel neuroimaging tools, the latest of which combines an advanced adaptive compensation technique with computation for extended detection. Unlike other approaches, theirs is a comprehensive method that addresses tissue scattering in an active way. “We proposed adaptive optics to overcome the scattering suffered by excitation light, and computation reconstruction to make use of the scattering signals of the emission light,” Kong explains.

Kong, an associate professor in the Department of Precision Instrument, was recognized in 2018 as an “Innovator under 35” by MIT Technology Review—which honored not only his team’s system developments, but also the assistance he and his colleagues have provided to neuroscience labs around the world seeking to duplicate and apply the innovations.

Starting with microscopy

A passive approach, laser-scanning confocal microscopy enhances depth by using a pinhole to spatially filter scattered emission light. A more active and direct way to reduce tissue scattering is use of long-wavelength light, considering that Rayleigh scattering varies inversely as the fourth power of the wavelength. In multiphoton microscopy (MPM), near-infrared light is used to excite signals based on nonlinear optical effects, which weakens scattering. Nonlinear effects ensure localized excitation, and thus eliminate crosstalk of emission light in non-descanned detection—however, the requirement of laser scanning in multiple dimensions reduces imaging speed.

Line-scanning temporal focusing microscopy (LTFM) is promising for providing high-speed imaging while maintaining tight axial confinement.2 In LTFM, excitation light is focused spatially along one axis while pulse dispersion is modulated along the other axis, using the principle of “temporal focusing” to ensure depth resolution. Compared to point-scanning, line scanning can improve imaging speed by more than an order of magnitude.3 However, tissue scattering in LTFM must be controlled to achieve maximum depth.

Excitation light

Tissue scattering of excitation light leads to focal distortion, decreased excitation efficiency in MPM, and reduced optical resolution and imaging depth. Adaptive optics (AO) can help address these limitations: In AO, sample-induced wavefront distortion is measured, and then a compensation wavefront is applied to the excitation light with an active element, such as a spatial light modulator, to recover the diffraction-limited focus. Specifically in LTFM, wavefront compensation is required for both spatial and spectral dimensions.

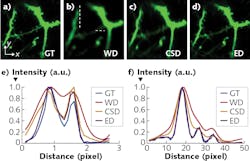

The Tsinghua University technique, called hybrid spatio-spectral coherent adaptive compensation (HSSCAC), is designed to fully correct wavefront distortions in LTFM.4 The researchers have used both simulations and experiments to verify the performance of their HSSCAC algorithm in retrieving global optimized compensation. With HSSCAC, the axial confinement of the excitation light can be maintained, suggesting its ability to overcome scattering of excitation light (see Fig. 2).Emission light

Especially in wide-field detection mode, LTFM suffers from crosstalk of emission light induced by tissue scattering. As with laser-scanning confocal microscopy, LTFM can use confocal slit detection, wherein a confocal slit is conjugated to line-shaped excitation, to spatially filter out the scattered emission light and improve imaging depth. Although such a technique can effectively address scattering-induced crosstalk between excitation lines, it cannot resist crosstalk along the excitation lines.

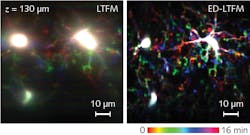

So, the Tsinghua University scientists proposed to remove the confocal slit for deeper detection, and to perform computational reconstruction. Their approach, called extended detection LTFM (ED-LTFM), is apparently the first wide-field two-photon imaging technique to extract signals from scattered photons and therefore effectively increase imaging depth.5 By successively acquiring the image of each line in two dimensions, ED-LTFM fully records all signals, scattered and unscattered. Following the application of the ED technique, the researchers used computational reconstruction to faithfully reconstruct the captured image stacks, and to incorporate Hessian regularization (a form of regression) for artifact reduction. Numerical simulations suggest that compared to both conventional LTFM and the LTFM based on confocal slit detection, ED-LTFM shows improved performance (see Fig. 3).The researchers expect that applying a femtosecond laser at low repetition rate and high pulse energy will enable enhanced imaging depth while maintaining a low signal-to-noise ratio.

Expanding limits

The researchers’ work demonstrates the ability of the combined HSSCAC and extended detection-based computational imaging techniques to minimize the effects of tissue scattering—of both excitation and emission light. The penetration depth of the method is limited by the available laser—the researchers report imaging at ~200 µm, but theoretically, the maximum depth would correspond to that of point-scanning two-photon microscopy (~1000 µm so far). With three-photon excitation, they expect to achieve still deeper penetration into tissue.

As with point-scanning MPM, the fundamental imaging-depth limit6 is ultimately attributed to the near-surface fluorescence, which can be minimized with focal modulation.7

The integration of the strategies described above could push the limits of imaging depth in scattering tissues even further. And the ability to resolve signals deep in the brain at high speed could facilitate the study of neural connection and functionality mapping.

REFERENCES

1. V. Ntziachristos, Nat. Methods, 7, 8, 603–614 (2010).

2. M. E. Durst, G. Zhu, and C. Xu, Opt. Commun., 281, 7, 1796–1805 (2008).

3. Y. Xue et al., Biomed. Opt. Express, 9, 11, 5654–5666 (2018).

4. Y. Zhang, X. Li, H. Xie, L. Kong, and Q. Dai, J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., 52, 024001 (2019).

5. Y. Zhang et al., Opt. Express, 27, 15, 20117–20132 (2019).

6. P. Theer and W. Denk, J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, 23, 12, 3139–3149 (2006).

7. Y. Zhang, L. Kong, H. Xie, X. Han, and Q. Dai, Opt. Express, 26, 17, 21518–21526 (2018).

Barbara Gefvert | Editor-in-Chief, BioOptics World (2008-2020)

Barbara G. Gefvert has been a science and technology editor and writer since 1987, and served as editor in chief on multiple publications, including Sensors magazine for nearly a decade.

![FIGURE 2. Resisting tissue scattering of excitation light is shown, including maximum intensity projection (MIP) along the z-axis of a 25-µm-thick image stack of a Cx3Cr1-GFP mouse acquired using hybrid spatio-spectral coherent adaptive compensation (HSSCAC; [a]), MIPs along the y-axis of an 18-µm-thick x-z stack (marked by the dashed box in [a]) acquired with full correction (left, compensating both the sample and optical system induced wavefront distortions) and with system correction (right, compensating the optical system-induced wavefront distortion only); intensity profiles along the indicated lines in (b) are shown in (c); magnified views of lateral area marked by the dashed box in (a), with full correction (upper) and system correction (lower) in (d); intensity profiles along the indicated lines in (d) are shown in (e); and the compensation wavefront at the back pupil of the objective is shown in (f). FIGURE 2. Resisting tissue scattering of excitation light is shown, including maximum intensity projection (MIP) along the z-axis of a 25-µm-thick image stack of a Cx3Cr1-GFP mouse acquired using hybrid spatio-spectral coherent adaptive compensation (HSSCAC; [a]), MIPs along the y-axis of an 18-µm-thick x-z stack (marked by the dashed box in [a]) acquired with full correction (left, compensating both the sample and optical system induced wavefront distortions) and with system correction (right, compensating the optical system-induced wavefront distortion only); intensity profiles along the indicated lines in (b) are shown in (c); magnified views of lateral area marked by the dashed box in (a), with full correction (upper) and system correction (lower) in (d); intensity profiles along the indicated lines in (d) are shown in (e); and the compensation wavefront at the back pupil of the objective is shown in (f).](https://img.laserfocusworld.com/files/base/ebm/lfw/image/2019/11/1911LFW_bg_f2.5dc48a435c338.png?auto=format,compress&fit=max&q=45&w=250&width=250)