APD Arrays: Geiger-mode APD arrays detect low light

Solid-state photodetectors have evolved in their ability to detect low levels of light. Building upon silicon photodiodes, novel solid-state detectors have been developed to detect increasingly lower levels of light. The latest addition and most sensitive solid-state detector to date is the Geiger-mode avalanche-photodiode (APD) array, which is capable of detecting a single photon.

Silicon photodiodes convert light into an electrical signal. This conversion occurs when photons having more energy than the bandgap of the detector material are absorbed, exciting an electron from the valence band of the semiconductor to the conduction band, where it is read out as signal. Avalanche photodiodes use the same process, but they generate internal gain using an avalanche multiplication process. An avalanche region is produced within the APD, creating an area of very high electric-field strength. When a photogenerated (or thermally generated) electron in the conduction band moves into the avalanche region, the electric-field strength is sufficient to accelerate it to the point at which it can cause “impact ionization” and liberate another electron. Both of these electrons can be accelerated as well, creating an avalanche multiplication. This process results in detector gain. Typical gains for an APD are in the range of ten to a few hundred.

Geiger-mode operation can increase the modest gain of an APD to a more significant level. In a single-photon-counting APD (in Geiger mode), the electric field described above increases with increasing applied voltage, thereby increasing the APD gain. This works only up to a point. At some operating voltage, the semiconductor junction breaks down and the APD will become a conductor. In fact, the APD is stable above this breakdown voltage until an electron enters the avalanche region, resulting in the avalanche region breaking down and the APD becoming a conductor—this is known as a Geiger discharge. The current flow produced by the breakdown is large; therefore, the signal gain is large (more than 105) because a single electron resulted in a large flow of current.

A device that triggers once, however, is not a very useful detector, so a means to stop the breakdown or to reset the APD is required. Typically the reset is accomplished by placing a resistor in series with the detector. When the junction breaks down, large current flows through the resistor, resulting in a voltage drop across the resistor and in the APD. If the voltage drop is sufficient, the APD voltage will drop below the breakdown voltage and be reset. The discharge-and-reset cycle is known as the Geiger mode of operation.

Geiger-mode APD arrays

A single APD operating in Geiger mode has a limitation: it is essentially on or off. It cannot distinguish between a single photon and multiple photons that arrive simultaneously. One only knows that the APD was triggered; it is not possible to tell if a single photon or multiple photons triggered the Geiger discharge. Single Geiger-mode APDs are suitable for photon counting at very weak light levels only.

Photon counting is a signal-processing technique that converts the output signal generated by a single photon into a digital pulse that is counted. No additional analog-to-digital converters are needed because the photon-counting circuit does the conversion. Photon counting follows Poisson statistics, so the signal-to-noise ratio is simply the square root of the number of signal counts. If one needs to improve the signal-to-noise ratio, the count is extended for a longer period of time (a count four times longer improves the signal-to-noise ratio by a factor of two).

An array of Geiger-mode APDs connected in parallel can overcome the limitation of a single device. These recently developed arrays can distinguish multiple-photon from single-photon events. One example of these devices, generically known as silicon photomultipliers, is the multipixel photon counter (MPPC) from Hamamatsu Photonics (see Fig. 1).

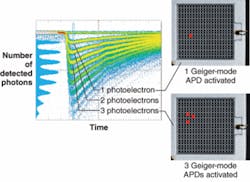

The sum of the output from each APD pixel forms the MPPC output. This allows the counting of single photons or the detection of pulses of multiple photons (see Fig. 2). When photon flux is low and photons arrive at a time interval that is longer than the recovery time of a pixel, the MPPC will output pulses that equate to a single photoelectron. The pulses can be converted to digital pulses and counted as described above. When the photon flux is high or the photons arrive in short pulses (pulse width less than the recovery time), the pixel outputs will add up, as shown in Fig. 2, as the 2-photoelectron and 3-photoelectron pulses. In this case, the MPPC is behaving in a pseudo-analog manner because it can measure the incident number of photons per pulsenot possible with single photon counting APDs.Additional advantages of the MPPC are high gain and low multiplication noise (noise added by the multiplication process). The high gain makes detection of a single photon possible—a single detected photon produces a measurable signal. While single photon counting APDs could also detect single photons, they require cooling down to -30°C or -40°C. Furthermore, the active area of these devices is very small (typically less than a few hundred microns). The MPPC has an active area of 1 × 1 mm or 3 × 3 mm and can count photons at room temperature.

While the MPPC has many advantages, it is not perfect. One disadvantage is its sensitivity to temperature changes. Geiger-mode operation reduces the temperature sensitivity, but temperature stabilization or compensation is still required for any application using MPPCs.

The dark counts produced by the MPPC are much higher than for a similar PMT due to the lower work function of silicon. However, dark counts are not the same as dark noise. Since photon counting follows Poisson statistics, the standard deviation in the number of counts is simply the square root of the number of counts. This means that an MPPC with 400,000 dark counts has a dark noise of 632 counts. In principle, one could get a meaningful signal-to-noise ratio from about 1000 detected photons.

Applications of the MPPC

Photon counting and the MPPC in particular can be used in a variety of applications. In a flow cytometer, for example, the major components are a fluidics system, a laser, optics, photodetectors, and electronics. As cells pass single-file through the laser beam, they scatter light and possibly fluoresce. The forward-scattered light indicates the size of the cell, while the side-scatter light indicates its structural complexity. The fluorescence of any fluorophores bound to the cell indicates the presence of a specific cellular structure or biomolecule.

In flow cytometry, light from scattering and fluorescence are typically collected by photodetectors, usually PMTs. However, multipixel photon counters can be used as an alternative. They offer high photon detection efficiency, high gain, and detection limits near those of a PMT. The high dark count of an MPPC is not an issue because flow cytometry uses threshold levels—effectively cutting off the contribution from dark counts and only allowing higher signals to be detected. The dynamic range of the MPPC could be an issue though.

Another MPPC application is high-energy or particle physics, which studies subatomic particles like neutrinos. As neutrinos travel through space, they oscillate between three types or “flavors”: νe (electron neutrino), νµ (muon neutrino), and ντ (tau neutrino). While the conversion of νµ to ντ has been studied, much is still unknown about the conversion of νµ to νe. The Tokai-to-Kamioka (T2K) experiment in Japan is intended to shed light on the nature of this phenomenon with the MPPC playing a vital role. Next year, the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex (Tokai, Japan) will send an intense neutrino beam to the Super Kamiokande (Kamioka, Japan) 295 km away. By measuring and comparing the amounts of νµ and νe at the start and end of the beam’s journey, physicists hope to observe the disappearance of νµ and the appearance of νe as the neutrinos oscillate.1, 2 The initial and final measurements will be performed by near detectors (ND280) and the Super Kamiokande, respectively.

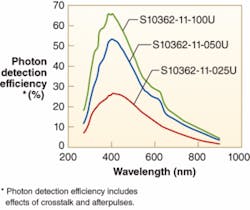

To detect neutrinos, the ND280 detectors will use thousands of scintillators coupled to photodetectors by wavelength-shifting fibers. The MPPC from Hamamatsu Photonics was chosen as the photodetector for the ND280 because it fulfills most of the requirements. The MPPC is compact and can withstand the 0.2 T magnetic field. It also has gain greater than 5 × 105, and its PDE is higher than the quantum efficiency for a typical PMT. Although the combined crosstalk and afterpulses in an MPPC is higher than the ideal 10%, the measured values in 300 devices (13% to 22%) are still low enough to allow the MPPC to be used.3 About 55,000 pieces of MPPC will be delivered for the ND280 particle detectors.

The MPPC represents a revolution in solid-state detection. It is now possible to count photons in very compact and low-power applications at room temperature.

REFERENCES

1. T2K Neutrino Experiment website (http://jnusrv01.kek.jp/public/t2k/)

2. T2K-ND280 website (www.nd280.org/info)

3. S. Gomi et al., “Research and development of MPPC for T2K experiment,” Proc. Int’l. Workshop on New Photon-Detectors, June 27-29, 2007, Kobe, Japan.

4. S. Uozumi, Proc. the Int’l. Workshop on New Photon-Detectors, June 27-29, 2007, Kobe, Japan.

5. P. Webb et al., RCA Review, Vaudreuil, Quebec, 1974.

6. K. Yamamoto et al., IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium, 2007.

7. Multi-Pixel Photon Counter catalog from Hamamatsu Photonics K.K.