With the election behind us, the business of running the federal government has begun. By mid-October nearly a dozen think tanks and scientific organizations had published roadmaps for the new president on how to create a strong science and technology team that will guide policy over the next four years. What’s evident in each report is the pressing need to name a science advisor before the inauguration and to use that individual’s expertise when filling the 75 or so top-level science and technology positions in government.

The new president has a real opportunity. Because science, technology, and engineering drive innovation, by promoting these areas we can improve our economic stability at home and extend our hand globally. The right team led by a science advisor versed in policy-making and well-respected in the science and engineering communities can bring real change to Washington and the country. But finding the precise mix of chemistry and credentials to manage the $142 billion federal investment in science and technology may prove challenging.

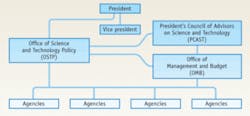

When the president and the science advisor (director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy) have a good relationship, the advisor can coordinate activities between federal agencies and the White House councils (not only the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, but also the Economic Policy Council and others). Communication with the Office of Management and Budget is critical when it comes to developing the federal science and technology budget requests sent to Congress.

Required: An interested president

The role of science advisor has flourished or floundered depending on a president’s willingness to respect and listen to his advisor. A study in evolution over the last 60 years, the science advisor’s position has been everything from champion, as was the case with Allan Bromley under George H.W. Bush, to persona non grata in the Carter and Reagan Administrations.

Federal science-policy observer William Blanpied, visiting senior research scholar at the National Center for Technology and Law, George Mason University, Fairfax, Va., notes that the two presidents who did the most for science policy were Gerald Ford and George H.W. Bush. “Ford revived the position of science advisor and science policy which had fallen apart during the Nixon Administration,” says Blanpied. Ford was responsible for providing the federal government with its first coherent approach to science policy. He pushed legislation through Congress to establish the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), which advises the president on issues related to science and technology that may have an impact the nation.

George H.W. Bush appointed Bromley almost immediately after the 1988 election and gave him the title of Assistant to the President. Titles are everything in Washington and for Bromley the title also meant access. Bush kept him close by the West Wing in the Old Executive Office Building which houses most of the White House staff.

Required: Presidential access

Think-tank reports agree that the president should give the science advisor the title of Assistant to the President for Science and Technology and that the advisor should have frequent contact with the president. In the case of the most recent advisor, John Marburger, who is a fine scientist and hard-working fellow, titles and access were limited. Marburger wasn’t confirmed until October 2001 and remained “Science Advisor to the President” throughout his tenure. His office was also a distance from the White House complex. “Marburger was marginalized,” says John Porter, chair of the National Academy of Sciences Committee on Science and Technology in the National Interest.

Given strong presidential support, the science advisor can act as a clearinghouse and coordinator for the federal science and technology enterprise. Not only does the advisor provide counsel to the president but serves as the director of OSTP, cochair of President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), and can play a key role in the budget process by working with the Office of Management and Budget to guide federal science agencies as they prepare their annual requests for funding. PCAST was originally established by George H.W. Bush in 1990 as an advice forum on technology, research, and math and science education. Members are drawn from the private sector and academic communities.

With the right leadership OSTP can also work with other White House groups such as the Economic Policy Council, the Domestic Policy Council, the National Security Council, and Homeland Security Council. Authors of “OSTP 2.0 Critical Upgrade,” produced by The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, suggest that by creating a dialogue with these groups, OSTP will be able to leverage innovation efforts from each and provide a more coherent S&T policy.

Required: Fast-track nominations

Many political appointments get bogged down because of cumbersome rules and procedures. The National Academy of Sciences report Science and Technology for America’s Progress: Ensuring the Best Presidential Appointments in the New Administration recommends the new president streamline the nomination process so that political appointees are not “in limbo” while waiting for Senate confirmation.

Under the current system, when a nominee agrees to serve in the administration they often take leave from their jobs, which may jeopardize their health insurance and pension coverage. “What does a nominee do for eight months–the average time it takes to move through the process?” asks Porter. Part of the delay comes from a dual system of scrutiny. Nominees must submit to background checks from the White House and the Senate.

Financial disclosure requirements also make government service less appealing for many would-be appointees. The NAS report calls for “eliminating many of the restrictions associated with the use of blind trusts” and guaranteeing continued health insurance and pension coverage for nominees during the confirmation process.

Required: Willingness to serve

Despite the clumsy approval procedures for nominees, many who undertake government service find it a way to give back to the nation. “Each of us in America has to embrace public service,” says Porter. “We must encourage the best people to step up.” Professional societies can play an important role in identifying leaders in their particular disciplines who could bring new ideas to government. These groups should encourage women, minorities, and young investigators through internships and fellowship programs.

Of the 1,000 federal advisory committees nearly half deal with science and technology. These committees are set up to serve as independent sources of guidance in policy areas across the spectrum of science and engineering. Filling these positions has been problematic in past.

Procedures for appointing members are not standardized or always transparent. Different categories of membership such as “special government employee” or “consultant” carry different levels of financial disclosure. The NAS report recommends that a new administration clarify and make explicit the process for nominating individuals to advisory committees as well as emphasize that nominees be chosen based entirely on their technical expertise and qualifications.

Required: A partnership for S&T

The new science advisor will have a tough job. He or she must find a way to capture the president’s ear, the ear of the science community and Congress, and the ear of the American people. Competing domestic and foreign issues will require a nimble individual able to see the big picture and skillfully demonstrate how science, technology, and engineering advances impact alternative energy development, national defense, and public health, among others. But the science advisor can’t speak in a vacuum. As Blanpied observes, “A president committed to science who says, ‘This is what we have to emphasize, this is what we have to fund. That would really bring things home.”

REFERENCES

Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Critical Upgrade: Enhanced Capacity for White House Science and Technology Policymaking

National Academy of Sciences, Committee on Science and Technology in the National Interest, Science and Technology for America’s Progress: Ensuring the Best Presidential Appointments in the New Administration (2008).