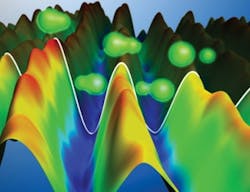

Attosecond pulses enable electron observation

To really understand a chemical reaction, scientists must be able to see how electrons move within molecules. Because of their lightning speed, however, it's been technically impossible to see them. But a European research team has now glimpsed the "unobservable."1

Marc Vrakking, Director of the Max Born Institute for Nonlinear Optics and Short Pulse Spectroscopy (MBI, Berlin, Germany) led the work with teams from across Europe, including the Attosecond Imaging group of Matthias Kling from the Max-Planck-Institut für Quantenoptik (Garching, Germany). The physicists examined the hydrogen molecule (H2), which consists of two protons and two electrons, to learn how ionization takes place in it. In this process, one electron is removed from the molecule, and the remaining electron is rearranged.

For the first time, "we really have the ability to observe the movement of electrons in molecules," Vrakking said. "First, we irradiated a hydrogen molecule with an attosecond laser pulse. This led to the removal of an electron from the molecule–the molecule was ionized. In addition, we split the molecule into two parts using an infrared laser beam, just like with a tiny pair of scissors. This allowed us to examine how the charge distributed itself between the two fragments–since one electron is missing, one fragment will be neutral and the other positively charged. We knew where the remaining electron could be found, namely in the neutral part."

Theoreticians from the University of Madrid joined the effort to make optimal interpretation of the measurements–and ended up adding completely new insights. Felipe Morales, a post-doctoral fellow at MBI, reports, "We nearly reached the limits of our computer capacity. We spent one and a half-million hours of computer time to understand the problem."

The calculations showed that the complexity of the problem was far greater than previously thought. "We found out that also doubly excited states, i.e. with excitation of both electrons of molecular hydrogen, can contribute to the observed dynamics," says Kling.

Vrakking describes it as follows, "We have not–as we originally expected–solved the problem. On the contrary, we have merely opened a door. But in fact, this makes the entire project much more important and interesting.

1. G. Sansone et al., Nature 465: 763-766 (2010)

More BioOptics World Current Issue Articles

More BioOptics World Archives Issue Articles