Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST; Boulder, CO) and the Naval Research Laboratory (NRL; Washington, DC) have addressed the issue of biosensor, or lab-on-a-chip, shelf life, showing how these chips could be made to last for months or more until needed.

NISTâs John Kasianowicz has spent decades trying to create technologies that will enable doctors to perform fast, real-time chemical analysis, and one promising approach involves building arrays of tiny pores, each small enough that only one protein or DNA molecule at a time can pass through and be identified. As our bodies respond to infection or other disease states, our cells release different proteins, and measuring the concentrations of these chemicals in a blood sample can provide a quick snapshot of our health. A membrane peppered with large numbers of these ânanoporesâ might give doctors a way to take that snapshot easily, if it could be mounted on a biochip compatible with electronics and computer technologies.

âBut these chips need to have a long shelf life,â says Kasianowicz. âAs it stands, we make nanopore membranes from fatty lipids that arenât robustâthe membranes only last a week or so. We wanted to extend that lifetime substantially.â

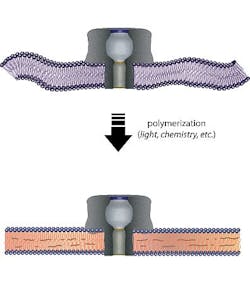

Kasianowiczâs and Devanand Shemoyâs (NRL) research teams explored the possibility of turning the lipids into polymers, the sorts of molecular chains used in plastics. Polymerizing the lipids made them tougher, but the question was whether doing so would somehow render the nanopores ineffective at trapping and identifying the blood serum proteins, because the process either squeezes or stretches the tiny membrane holes dramatically. Tests at NIST showed the nanopores performed just as well as before, meaning polymerized membranes could work on a biochip.

âConceivably, chips made with polymerized membranes could last a year, perhaps much longer,â Kasianowicz says. âThe nanopores still allow molecules to flow through for characterization.â

The NIST team patented the concept,1 which shows specifically that the nanopore will still function in a polymerized environment. Kasianowicz says the next step will be to demonstrate that the polymerized membranes will last when they have been attached to a chip, something their results have not yet shown.

âWeâre optimistic thoughâbased on observations weâve made in previous research, it should work in principle,â he says. âWe hope this is the next step toward allowing medical professionals to judge health conditions based on immediate blood analysis, which should be more accurate than using day-old samples.â

REFERENCE

1. D.K. Shenoy, A. Singh, W.R. Barger, and J.J. Kasianowicz, "Method of stabilization of nanoscale pores for device applications," U.S. Patent 8,294,007 (October 23, 2012).

-----

Follow us on Twitter, 'like' us on Facebook, and join our group on LinkedIn

Subscribe now to BioOptics World magazine; it's free!