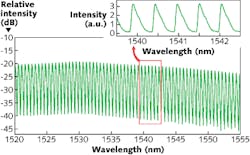

A type of optical filter developed by engineers at Beijing Jiaotong University (Beijing, China), the University of California–Los Angeles, and the California NanoSystems Institute (Los Angeles, CA), and aptly called a JAWS (jammed-array wideband sawtooth) filter, has a spectral shape that looks like a row of sharp teeth (they’re even slightly serrated).1 With its fine sawtooth pattern, the filter is useful for quickly and sensitively interrogating fiber Bragg grating (FBG) sensor arrays.

The filter is built around a virtually imaged phased array (VIPA), which is a side-entrance hollow Fabry-Perot etalon. The slightly converging entrance beam is focused on and strikes one internal surface of the etalon at an angle not far from normal incidence, then bounces back and forth within the etalon to produce the phased array of virtual sources, which act as a diffraction grating with multiple orders that overlap each other as diverging beams. If a partially blocking intensity mask is placed after a collimating lens, the sawtooth spectrum is produced.

The experimental VIPA etalon has a 2.4 mm cavity length and mirrors with reflectivities of 99.5% and 95%. The broadband beam, which exits a fiber and is collimated, is focused in one dimension by a cylindrical lens with a 100 mm focal length and enters the etalon at an angle of 4°. Upon exiting the etalon, the light is collimated in the same dimension with another cylindrical lens with a 150 mm focal length.

The setup can create a sawtooth spectral shape over a more than 30 nm spectral band. The tooth size and etalon free spectral range are 0.4 and 0.5 nm, respectively, resulting in an 80% duty cycle for the sawtooth pattern. The optical loss of the filter is about 20 dB, which is sizable and can be compensated by an optical amplifier if necessary. Tooth spacing is varied by changing the etalon cavity length.

Two trial runs

In conventional strain- or temperature-sensing FBG sensor arrays, it is difficult to interrogate the sensors at both high speed and low cost because the equipment needed can include wavelength scanners, analog-to-digital converters, or digital processors. So the JAWS researchers hooked their relatively inexpensive setup to a three-element strain-sensing FBG sensor array (1541.1, 1541.6, and 1542.2 nm center wavelength); strains were converted to intensity changes. The intensity change was linear as a function of strain, as compared against FBG measurement using an optical spectrum analyzer.

The researchers also combined their device with dispersive Fourier transformation to create ultrahigh-frequency sawtooth optical waveforms at a 1.52 GHz fundamental frequency. (Dispersive Fourier transformation is an optical technique to map a spectral band shape to a temporal waveform shape.2) Such waveforms are useful in wideband communications and high-speed signal processing.

REFERENCES

1. Z. Tan et al., Opt. Exp., 19, 24, 24563 (2011).

2. B. Jalali et al., Proc. Lasers Electro-Opt. Soc., 1, 253 (2001).

John Wallace | Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.