For all of the sophisticated technologies developed, welding still remains the simplest of concepts

Welding, as the dictionary defines, is a process to “unite (pieces of metal, plastic, etc.) by heating until molten and fused or until soft enough to hammer or press together.” Seems simple enough.

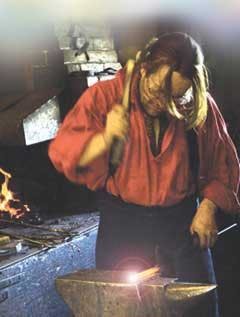

Not far from me is Old Sturbridge Village (OSV), a living outdoor museum, where one of the favorite exhibits is the blacksmith shop. Here an authentically garbed interpreter labors all day producing metal parts needed by the other exhibits in this pre-industrial America (1830) tourist attraction.

David Burk for Old Sturbridge Village

As in all the village's interpreted exhibits, the blacksmith comments on his work; the bellows-driven hot temperature of the coals, the selection of the metals needed for the parts to be joined, and the quenching and reheating process necessary to harden joined metals (today we call it joint weldability), pausing only to answer a query from a visitor intrigued by the combination of heat and muscle energy needed to produce a finished joint.

I, and many of my technically oriented guests, often quiz the blacksmith testing his knowledge of metallurgy; he is, after all, portraying a farmer supplementing his income by offering a service to “1830s villagers,” so what would he know about these technicalities. Even though OSV requires interpreters to be extremely well versed in the role they play, I am often surprised at the level of understanding he has of the joining process, although I shouldn't because it is an art or craft passed down since the Bronze Age.

Last month on this page, I mentioned the start of the modern age of welding—the introduction of the electric resistance heating process. From that point forward researchers have sought more efficient heating techniques to improve the welding process. For all of the sophisticated technologies developed it still remains the simplest of concepts: heat a material to its melting point and cause it to flow into another, cool it, and you have a joint. So I guess it's the source for generation of the heat and the unique characteristics of that heating process that separates one form of welding from another.

In certain fusion welding procedures we like to talk about low total heat input welding, where the amount of heat is only that needed to affect a weldable joint thereby reducing any unwanted heating of surrounding material. It is this localized heating and cooling concept that makes focused energy techniques like the laser and electron beam so attractive to metallurgists and welding and material engineers. For example, the right combination of energy converted to heat in a tightly focused spot producing a smooth joint in a flat sheet of metal rather than the potato chip results from the stick electrode process.

So, as Stan Ream succinctly points out in his essay on the ILS Website, laser welding has attributes that attract today's industrial designers, a part that is functional, easy to process in reduced steps, and under the right conditions can be transferred directly from the joining process to the next assembly step.

In the almost 5000 welding references on the ILS Website and those that will appear on these pages in increasing numbers this year, we will try to show you the many benefits, technical and economic, associated with laser welding. For ILS, 2009 will be the year of welding.

David A. Belforte

[email protected]