266nm DPSS laser micromachining

Approximately 10 years ago, the first commercially available diode-pumped solid-state (DPSS) lasers became available in the 355nm wavelength. These lasers have a Gaussian beam and near TEM00 mode with M2 near 1. The Gaussian beam along with the high achievable repetition rates make this laser source ideal for applications where material has to be cut, drilled, or marked. Most materials respond well to the 355nm wavelength, and we have presented comparative results for polymers (ILS, May 2002) and metals (ILS, December 2004) in this publication previously. The DPSS lasers have many other attractive features, but the most attractive feature is that when you turn them on, they work, and they continue to work for thousands of hours with little or no maintenance. At present the highest average power commercially available 266nm laser that we are aware of is the 3W Avia.

When using a laser for materials processing it is all about absorption (Beer’s Law). The more a material absorbs, the better, in general, the processing results can be. Furthermore, the key to clean and precise processing with little heat affected zone is peak power density on target-some combination of high pulse energy, short pulse length, and small spot size combined with near 100 percent absorption. Because of the shorter wavelength, we naturally get smaller spot size and shorter pulse lengths with the 266nm laser than the 355nm laser for similar optical configurations. We have found that we can do anything with the 266nm laser that we can do with the 355nm laser, usually better (although not always as fast), and we can do many things with the 266nm wavelength that we cannot do with the 355nm laser.

Most 266nm lasers use galvanometer beam delivery systems, which can be simple but effective. The focal length of the field lens defines the optical resolution and working field on target, but most optical set-ups have from 1-in to 6-in fields with spot sizes ranging from 10 microns to 30 microns. We have built a custom machine using a Scanlab 3-axis scan head that has a 30-in field. Fixed beam delivery systems can also be used if a co-axial gas assist is required, but for most applications the significant decrease in speed is undesirable, the notable exception being in high-volume applications where simple straight lines are drawn-an example being wafer scribing. In any application involving circles, arcs, or complex shapes, the galvo approach is by far more typical and productive. A huge advantage of any DPSS laser is the ability to use CAD files input to the laser control software with little set-up requirements, thus reducing set-up time and cost. Compared to an excimer laser, the set-up on any DPSS laser with good software is straightforward.

If you need UV photons, then 355 nm is the first choice, 266 nm the next best choice, and excimers are the last alternative. This should not be construed as being negative on excimer lasers: it is simply a fact that these lasers are more costly and difficult to operate in general than DPSS lasers, although there are still many jobs that can be done more efficiently with excimer lasers and also many jobs that cannot really be done by any other method. Excimer lasers are best utilized where small feature size and clean features are more important than speed and cost and in particular they can be economical if the features are small, dense, and uniform.

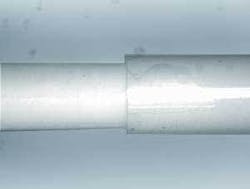

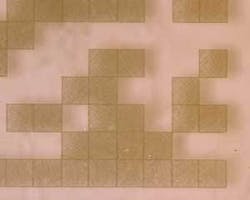

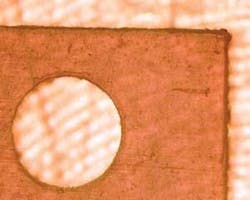

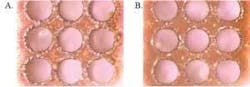

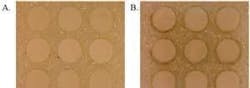

Figure 1 shows a bio-absorbable material on a ceramic mandrel. This end cut has been made with a 266nm laser and it can be seen that this laser cut is as clean and straight as can be achieved with a 193nm excimer laser, typically used for this application. There are, of course, a few tricks, but it is possible to get nice cuts in this material, which actually has a decent absorption but is extremely thermally sensitive. As bio-absorbable stents replace metal stents, it may be possible to see hundreds of 266nm lasers in use on just this product. Figure 2 shows a 2D matrix code marked inside glass. Surface marks usually produce some micro-cracking or chipping even using UV lasers, but the 266nm laser allows us to actually mark inside the bulk material with a readable mark that does not cause stresses that propagate. Figure 3 shows Teflon that has been cut with a 266nm laser. Typically, this material has very low absorption at 266nm and shows a lot of melt when laser cut unless one goes to 193 nm or even better 157 nm. In this case, we can find processing conditions that allow us to get excimer quality cuts at much higher speeds and without the need for evacuation or purging of the optical path. Figure 4 shows two pictures of SS, 1.2-mils thick, with an entrance D of about 120 microns and a pitch of about 170 microns center-to-center. It is clear that the 355nm laser (a), while doing a good job, is far surpassed in quality using the 266nm laser (b). The same also applies for Figure 5 where we show the same holes and pitch made in 8-mil thick alumina ceramic. The comparison shots (Figures 4 and 5) were done using approximately the same spot size (about 15 microns) and energy density on target, scan speed, and so on, only using different wavelength DPSS lasers.

In 2002 we wrote, “Give me a UV source with very short pulse length (1 ps or less) with high repetition rate (> 50 kHz), high power (> 10W), low M2, and with a flat top, collimated beam, all in a compact and reliable package.” All of these desires can now be met, although not all in the same package—yet. We have since altered our desires on the pulse length and we now think that we can live with a pulse length less than 1 ns and we have seen some very nice results using a 4ns pulse. For 266 nm, the 10W output power is not yet a commercial reality and from our discussions with various manufacturers it appears that, while everyone is always ‘looking to higher power,’ nobody is rushing headlong in this direction—at least they are not claiming to be. One might also extend the question to the 213nm quintupled wavelength and again it appears that nobody is working on this wavelength at all, mostly because there is not an identifiable near-term market where multiple units can be sold quickly and at high mark up. If we were to make our new wish list, we would only add to the above that we would like it all to be in a fiber laser configuration. In fact, we would be more than happy if we could get a UV fiber laser even if the pulse length is in the tens of nanoseconds range. UV fiber lasers are being worked on at present and this will become a reality, but they probably will not be a commercial reality for a couple years. 266nm beam shaping optics are a reality and this is the next step in our discovery.

In conclusion, short wavelength, short pulse length laser processing is the name of the game in the high resolution world. There exist now several UV laser sources that can be used to address a variety of applications. Extension of the DPSS platform to include the 266nm wavelength has opened even more avenues than the 355nm lasers, such as glass marking and drilling, clean processing of medical devices—especially in materials that do not absorb well at longer wavelengths—near-burr-free thin metal processing and clean drilling of ceramics. We are always looking for the newest, coolest laser that allows us to address more customer requirements and hopefully the coming year will bring new toys.

About the Author

Gabor Kardos

Gabor Kardos is contract manufacturing manager at PhotoMachining (Pelham, NH).

Oleg Derkach

Oleg Derkach is applications specialist at PhotoMachining (Pelham, NH).

Ron Schaeffer

Ron Schaeffer, Ph.D., is a blogger and contributing editor, and a member of the Laser Focus World Editorial Advisory Board. He is an industry expert in the field of laser micromachining and was formerly Chief Executive Officer of PhotoMachining, Inc. He has been involved in laser manufacturing and materials processing for over 25 years, working in and starting small companies. He is an advisor and past member of the Board of Directors of the Laser Institute of America. He has a Ph.D. in Physical Chemistry from Lehigh University and did graduate work at the University of Paris. His book, Fundamentals of Laser Micromachining, is available from CRC Press.