Combo units move out of the manufacturing sector

It appears that 2007 will be a good year for installations of combination laser/turret/punching sytems. The first laser cutter shown and sold in the USA in 1978 was a combination system sold to a Canadian sheet-metal job shop; for the next few years this equipment enjoyed acceptance mainly by the manufacturing sector, led by companies such as John Deere, which found the combination advantages ideal for processing sheet metal for harvester cabins.

With the advent of standalone laser cutters, an attractive unit for sheet-metal job shops, combination machine sales trended to remain in the manufacturing sector as the dual feature was judged to be uneconomical for job shoppers, who argued that tying up one process while the other worked was ineffective. However, as time passed and systems became more productive, this situation changed somewhat. So ILS set out to interview, with the assistance of Amada America (www.amada.com) three combination machine users-one from the job shop sector, one from manufacturing/contract processing, and one pure manufacturer.

PDS (Premier Dedicated Solutions) located in Anaheim, CA, is essentially a job shop within its parent company Premier Mounts, which, with more than 1000 products and a global network of dealers, is one of the world’s largest suppliers of mounts-everything from plasma and LCD displays to projectors and monitors. PDS supplies Premier Mounts with the sheet-metal components used to fabricate these mounts.

Located in 45,000 square feet of the parent’s 110,000-ft2 facility, PDS finds itself deeply involved with the company’s custom mount business, which generates sales from all over the world. This custom work can entail a multiscreen-monitor display for a casino or simply a plasma or LCD setup for someone’s home patio or pool area.

Prior to establishing the PDS division, Premier subcontracted all its sheet-metal fabricating work to local vendors. In 2005, Rich Pierro was hired as a consultant to set up a fabricating shop within the company. Looking at the projected production and custom work being generated, he decided to equip the new shop with an Amada press brake and an Amada EMLK combination laser/turret punch. Installation was in July 2006, and production began in September. The shop has grown and prospered quickly. Asked why he selected a combination machine rather than a standalone laser cutter and separate punch, Pierro says floor space dictated selection of this unit.

Now a 35-man operation runs on a one-day/8h and four-day/10h shift schedule. Pierro is already planning to add a third shift to meet the growing market demands for flat-screen display mounts, as Premier celebrates 30 years in business with booming sales. Also a limited but lucrative job shop business has evolved as word got out about the company’s fab capabilities.

PDS now utilizes the original two machines plus another Amada press brake, a machine shop with two CNC lathes and a CNC mill, presses, an Amada shear, an automatic band saw, TIG, MIG, and spot welding, and full state-of-the-art powder coat line. It also brings in outside work for the paint line because of its large capacity. PDS cuts mostly 12-gauge mild steel and a range of 0.020- to 3/8-in.-thick mild steel, aluminum, and stainless steel.

Pierro selected a combination system because of its flexibility to do two operations on one unit. PDS is set up to produce quick turn prototypes designed for special mounts. So the company wants to produce prototypes quickly as it earns a lot of follow-on business.

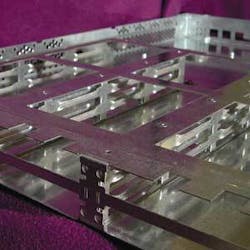

PDS does custom one-offs; a customer will send an idea, and PDS will take this and develop a special mount. This capability has driven the competition away from the special markets. Custom mounts can range into the thousands of dollars. In fact, prototyping custom mounts is a PDS specialty and is a major portion of its laser cutting business and a reason why the laser/turret punching system makes sense for its fabricating needs. An example of complex custom mounts is the multiscreen displays that are typically seen in casinos, where 16 flat-screen display setups are used in what is known as a video wall.

Asked why, other than floor-space limitation, he chose a combination machine, Pierro says, “I can ramp up production punching runs and just use the laser for prototype. We interrupt production a lot and I don’t like doing it, but we have only the one machine for our small floor space. But we are used to doing it. I can simply load the laser program into the machine and quickly cut the prototype and then switch back to the production punching run.”

CNC lathe parts used in OEM medical equipment

Once the project gets to the production phase PDS steers away from the laser and punch as much as possible, even for runs of 50 to 100 parts; changing jobs is quick with a standard turret tool configuration. The nature of the daily work flow is that there will be interruptions, so the shop is tuned to switching back and forth. Pierro uses the second shift to utilize hours for punching production runs. Daytime hours are spent on short production runs and prototype work.

Pierro is happy with the Amada laser/turret punch, and says it serves him well. There was a short learning curve on installation due, he says, to the Windows-based controller that really helped in training people. Operators are trained for both shifts, but he admits that it is always difficult to find people who want to work in manufacturing. However, he was recently pleasantly surprised to find untrained people, bring them on-board, and with a little training get them to the point where they operate independently.

With the current growth pattern and increased demands for cutting, Pierro is planning to add additional employees in fabrication and engineering and another laser, but says this will be a flying-optic, standalone unit because the speed will be fast enough to handle increased cutting demand.

Sheet metal shop

Al Stucky Jr. had been working for 10 years for a large San Francisco Bay Area fabricating shop when he decided in 1984 to start his own business. His reason, “It seemed an appropriate time in my life to give it a try. If not now, when?”

He, along with a partner with many years experience in the field, started from scratch, without any backlog of business. They went about buying and setting up the equipment in a rented building in San Clara, CA. They called the company MASS Precision Sheetmetal, after the first initials of their names.

The Bay Area was just booming with computer companies led by Apple, Hewlett Packard, and IBM, and orders for sheet-metal cabinets began to roll in. Proceeding carefully, he added new auto indexing CNC turret punching equipment and press brakes, selecting Amada as the primary source because he liked that equipment, and, as he freely admits, that company’s financing was attractive. He chose a unit with an autoloader that got him started in automation, which is a trend he continues today. By the end of the first year he added a second turret and increased the press brakes from two to four. Over the succeeding years he has added 12 more turrets along with two press brakes for every turret added.

At the end of the second year he moved from the 6500-ft2 building to one 10,000 ft2 and added another 10,000 ft2 a year over the next two. In 1989 he moved to San Jose, CA, and into a 40,000-ft2 building. Today the company is in five buildings totaling more than 220,000 ft2, including a facility he purchased when he bought a machine shop in Campbell, CA. Total employment today is 450, making MASS one of the top shops in the area.

The Amada 3610 EML combo servo-electric punch press is combined with a 4000-watt laser.

In the 1990s, the local economy boomed, and fab shops were hard-pressed to keep up with the demand for sheet-metal cabinetwork. This was the “golden” period for laser cutters, as they quickly began to replace turret punch presses, and in a decade many dozens of standalone units were installed in Silicon Valley. MASS got a good share of this work, not only because of its precision work, but also because the company was agile and could turn around jobs in a few days that others took weeks to complete.

Precision fabricated electrical enclosure designed by MASS engineers is used in the telecommunications industry.

In 1993, after hearing about the advantages of laser cutting mild steel Stucky bought a Lasmac laser from Amada. He confesses to being a little slow to adopt laser cutting into his company. When asked why, he admits to a prejudice for turret punching from his background. He quickly found that tooling costs were reduced using the laser and that it offered more flexibility in setup for production runs. In 2000, he added a Mitsubishi 2512LZ flat sheet cutter because he could do more options on a sheet. From 2000 to 2003 sheet-metal fabricating in the Bay Area dried up as the telcom bubble burst, and shop after shop went under while MASS survived, slightly wounded.

Business recovered in 2004, and Stucky realized he needed a stronger installation; he bought a barely used Amada Apelio 367, 58-station turret, 2-kW CO2 laser unit. This really got MASS into combo processing and opened the company’s eyes as to what this unit could do for the company. His operators began to find myriad ways to use the combination machine.

Asked about negative comments on the economics of combo machines, that is, tying up one function while the other is running, Stucky admits he harbored the same thoughts about not fully utilizing the machine. Even with a steep purchase price he realized he saved considerable time with setups as they have a lot of special shapes to try that the CAD system and the laser knock off readily. So he saved money on programming, tooling, and setup.

Asked about not using the standalone lasers, he also has a used Mazak Turbo X48, he says, and they are either older machines or are specialized for certain product he runs. He acknowledges that modern standalones are greatly improved and says the next laser he purchases will replace at least one of his punching machines.

Joe Mirabel, who is in charge of the turrets and lasers, says, “Much of the work we do requires parts with certain forming features and countersinks that lasers cannot process.” The combo allows them to punch, form, and laser cut at production speeds.

Last year, Stucky bought a new Amada EML 3610 punch laser with a 4-kW CO2 laser because of the success of the Apelio. It had been booked solid, giving him confidence that the new unit would prove beneficial to the company. Now both combo units are heavily booked. They run three shifts on the automated load/unload turrets and lasers. Volumes today can run up to thousands, but usual runs are 50 to 500. The company ships parts all over the world, even competing with Asia.

Mirabel says the laser units have met every expectation and have excellent uptime. MASS operators do minor service, and they only call on the suppliers when it is serious, which is rare. He says, “Laser cutting runs about 20% of machine time on the combo machines.” MASS mostly does mild steel in 20 to 10 gauge, some stainless, and aluminum.

Stucky says that his company is a precision sheet-metal manufacturer dealing with thin-gauge material for the electronic and medical industries, anything that goes in boxes, plus a machining team that can do all the machined parts. Finally, the company offers a complete solution, which includes full turnkey assembly.

Product manufacturer

A-dec, founded in 1964 by Ken and Joan Austin, is reportedly the largest domestic supplier of dental equipment. The couple started out with two products-one, a saliva-evacuation device-and they expanded from there to supply just about everything you see in a dentist’s office, except the hand tools. This includes chairs, stools, lights, cabinetry, and other accessories. From day one, A-dec believed in manufacturing all of its products in-house to ensure quality and on-time delivery.

Daniel Brownsworth, sheet metal plant supervisor at the Newberg, OR, company, told ILS that there are 14 buildings that contain machine shops, plastic manufacturing, assembly, sales, and engineering-all that is necessary to produce every aspect of the company’s product line, even though competent outside resources abound in the area. So from the beginning, as the company added new products, it added the production capability and capacity to manufacture in-house.

Brownsworth cites as an example the company’s purchase of an automated laser cutting system because the company was subcontracting a substantial amount of laser cutting work. At that time the company was not featuring products made of thin-gauge stainless-steel sheet or of heavy plate, so outsourcing made sense. Having joined the company five years ago as a manufacturing engineer, Brownsworth was asked to look into what, for A-dec, was a new technology-laser cutting of sheet metal-because A-dec was spending more than a million dollars a year for laser cutting.

A-dec manufactures all of the dental office equipment and furniture shown, except for hand tools, in its own facilities.

Once company management had decided to move into laser cutting he looked at everything available in the market, from standalone laser cutters to automated systems. Brownsworth is a machining guy with a background in machine tools and automated systems. It occurred to him that he could end up with a cell configuration where he had a punch, two storage towers, and a standalone laser, and the concept that bothered him was all the set-up time loading these systems was going to take. So he could have a fully automated system but only run what was set up due to the set-up time of the turret. He needed flexibility.

Because of the major corporate investment, he assessed the entire market and narrowed his choices down to a combination laser/turret punching system. The combination machine can maintain a standard turret load and use the laser to cut profiles and non-standard geometry. A standard turret machine would require custom tooling and be set up to accomplish non-standard geometry.

I asked him if he considered the argument that combination machine processing would mean the laser was idle while punching and vice versa. Brownsworth countered that a combination was economically sensible for A-dec and that a fully automated machine would eliminate up to 3000 hours of set-up time for two standalone systems. So he selected an Amada EMLK laser/turret punching system (see sidebar) because it came out on top in his market-research study and installed it in a newly renovated sheet-metal plant. This unit, the first of its type Amada sold, with a 4-kW CO2 laser and 5 × 10-ft. bed, was installed in mid-2006. Other than some start-up difficulties with the automation portion of the system, resolved in a few weeks, the combination unit was producing parts to specification.

This equipment is now running two 10h shifts, five days a week. Typically Brownsworth wants to use the punching unit as much as possible, because he can punch a hole faster than he can laser pierce and cut it. Because the punch has upforming, it is excellent for forming louvers, and these upform dies allow unattended operation. The laser is used primarily for profile cutting or for producing odd shapes. Standard holes are made with dies; otherwise the laser is used.

A-dec does some prototyping on the system, which is accomplished from files uploaded from its in-plant model shop. The flexibility of the combination machine allows prototyping to be done in a production environment. Zero setup makes the change to a new part transparent to the shop.

Production runs are in the hundreds, with many parts being 5.5 feet long. While the company still processes and powder coats mild steel, the trend is to stainless steel, which was another motivation for purchasing a laser system; stainless is hard on tooling for a punch but by using nitrogen the laser produces a perfect cut edge with no tool wear. Stainless is an option that customers now want. There is no special effort made to punch versus laser cut, whatever the need is it is accomplished in one setup. Material is usually 11 gauge and under, with thicker materials handled by a free-standing gantry-style laser that is also hooked up to the twin towers that can hold 88,000 lb of material.

According to Brownsworth, the machine is running 95% plus uptime, operating unattended most of the time. The only interaction with the machine is pulling finished products from the sheet. The system was purchased with expansion in mind, so A-dec can go to 24h/day operation easily.

ILS concludes that, based on these interviews, for certain companies, mostly based on part volumes and flexibility needs, the combination unit makes sense. For the three companies interviewed, it does, and each is enthusiastic about its equipment.

LASER /TURRET PUNCH

The EMLK from Amada America combines electric-motor punching technology with a hybrid-drive laser motion system creating a fast and efficient punch/laser processing machine. Currently available with 4 kW of laser power, it will also be available with 2.5 kW in 2008. The standard turret configuration has 58 stations, four of those being auto-indexing.

The EM technology allows for complete ram control and incorporates a small percentage of the parts required by hydraulic systems. This design uses a fraction of the electricity by generating, storing, and then using energy during the punching process.

The EMLK3610NT model can process a 60 × 240-in. sheet with one reposition on a brush table to reduce part scratches. A trap door allows parts up to 5 ft. wide to be dropped through. This unit can be combined with a load and unload system. A parts takeout unit removes parts and stacks them on a pallet or it can drop parts onto an intermediate conveyor for immediate retrieval.