Laser cutting provides quality parts for steel processor

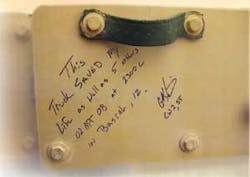

The words written in marker on a piece of armor plate compel your attention: “This truck saved my life as well as 5 others on 02 Apr 08 at 2300 in Basrah, IZ.” (see Figure 1).

The referenced truck is one of a family of armored fighting vehicles known as MRAPs (mine resistant ambush protected vehicles) deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan. In May 2007, US Secretary of Defense Robert Gates called the acquisition of MRAPs his department’s highest priority and earmarked more than $5.4 billion for the program. “The companies that have been awarded the MRAP contracts are ramping up their production capabilities…” he said last year. “I am pressing them very hard to see where they can cut the time scale as well as increase their production…You have to look outside the normal bureaucratic way of doing things and so does industry because lives are at stake.”

This is a message Ed Westerdahl III takes extremely seriously. Westerdahl, 47, is president and CEO of Service Steel Inc. Located in a former shipbuilding facility in Portland, OR, Service Steel has 12 processing bays and 25 overhead cranes capable of loads from five to 25 tons. “We routinely process steel plates up to 12 feet wide by 60 feet long weighing up to 40,000 pounds,” he says, calling his firm “especially successful at producing kitted parts and assemblies while meeting JIT delivery requirements.”

It wasn’t always that way. Service Steel was founded by Westerdahl’s father in 1982 and originally set up as a distributorship. The firm mainly supplied small fabricators and welders with sheets and bar stock. Any processing was limited to what a saw and a shear could provide.

Over the next 15 years, the company began to tentatively expand its steel processing capabilities, mainly in the areas of flame and plasma tables. Growth was “reactionary,” in Westerdahl’s words, averaging about 5% annually.

In 1996, Service Steel purchased its first laser and in 1997 Westerdahl took over running the company. “The steel distribution business in the Northwest was consolidating,” Westerdahl says of the time. “There were three other companies that did what we did, and we all found ourselves fighting over fewer orders with smaller margins.”

At the same time, OEMs and large suppliers in the automotive, heavy equipment, and other sectors were moving to outsourcing and JIT deliveries in a big way. Wanting to move beyond reactionary growth, Westerdahl began investing in capital equipment to move Service Steel from a distributor to a parts processor.

“It was a big transition and a new model for the company,” Westerdahl recalls. “The idea was to move from selling stock to small fabricators to supplying large manufacturers with finished parts.”

The perfect layout

In 2001, Service Steel moved to a former World War II shipbuilding facility across the Willamette River. “We had an 80,000 square-foot building where our overhead cranes were often gridlocked, which affected machine uptime,” Westerdahl says. “Our new facility was 300,000 square feet with 25 overhead cranes on multiple crane ways, which meant simultaneous distribution to all our processing bays. By design, the layout of a shipyard was perfect for the large steel processor we wanted to be.”

September 11, 2001, put the brakes on Service Steel’s growth, but after 2002, growth began to consistently accelerate. “Our market share has increased dramatically,” Westerdahl says, noting that his company exceeded 2007 sales by the end of June 2008. Employee head count has jumped from seven when the firm was founded to 130 now, making Service Steel the largest steel processor in the Pacific Northwest. Processing capability has grown from two burn tables to eight (two with integrated machining centers), nine lasers (two with sheet processing towers), and a full CNC machine shop with ˜50 pieces of equipment.

With its processing capabilities, square footage, and material handling, Service Steel has built a reputation for handling both large parts out of thick plate and small parts at high volumes out of sheet.

Westerdahl’s lasers are central to his effort, particularly with large parts. In the mid-1990s, acquiring lasers was an expensive undertaking for the company, but Westerdahl saw the capabilities for higher tolerances and elimination of secondary operations compared to the company’s flame tables and plasma cutters. “Back then, we were making motor-mount brackets for rock crushers out of three-quarter-inch steel,” he says. “Plasma cutting required extensive post-processing to remove the bevel from the cut and to clean up the holes. With the laser, it was clean in and out.”

Calling a 3kW resonator his “absolute minimum,” Westerdahl acquired a 6kW Bystar 4020 from Bystronic (Hauppauge, NY) earlier this year. “We’re routinely cutting one-inch plate in production, and this model had the nominal sheet capacity we needed (80 inches by 160 inches). We also had to have confidence that this model would process a whole plate of parts without blowouts.”

Westerdahl credits the Bystronic resonator on his new machine with supplying him an advantage. “In our world, laser cutting routinely operates at 80 to 90 percent of capacity. We’ve found the Bystronic resonator to be both more hardy and more forgiving. It will continue making good cuts in a wider range of operating conditions.”

Also, thick surface scale or a change in the chemistry in the workpiece material, such as in heat-treated armor, can make laser cutting more problematic. Westerdahl would experience this first-hand when Service Steel Inc. was awarded its first contract for MRAP components last summer.

null

Every single armor part

Improvised explosive devices (IED) have been cited as causing the majority of US military deaths in Iraq. To combat this, the Department of Defense (DoD) began contracting concurrently with several vendors obtaining designs for MRAP vehicles and buying tires and steel through the Defense Logistics Agency to accelerate production.

“This is not a business-as-usual process,” said John Young, MRAP task force chairman in October of last year. “I have seen tremendous coordination, collaboration, and cooperation, all in an effort to achieve the goal this team shares with Secretary Gates—urgent delivery of the maximum number of MRAPs to put this capability in the hands of our forces.”

With an armored V-shaped hull including armored walls, floors, and side and end panels, the MRAP is designed to survive IED blasts. Category 1 MRAPs are four-wheeled vehicles that carry four passengers plus a crew of two. Category 2 MRAPs have longer hulls and six wheels and can carry eight passengers in addition to the crew of two.

In a speech last October, Marine Corps Commandant Gen. James T. Conway called the MRAP the gold standard of force protection. “We had an incident the other day where an MRAP was hit with a 300-pound charge right under the engine,” he said. “Now I mention the size of the charge because we were testing them at Aberdeen (Proving Ground, Aberdeen, MD) against 30- and 50-pound charges.

“But a 300-pound charge went off right under the engine,” he continued. “It blew the engine about 65 meters away from the vehicle, caused a complete reversal of direction on the part of the MRAP, but of the four Marines inside, the regimental commander put one on light duty for seven days and the other three continued with the patrol. So it’s an amazing vehicle in terms of the protection it gives to our people against these underbody blasts.”

Service Steel has cut every single armor part on an MRAP, including side panels, roof panels, floor, V-hull, rear wall, and rear ramp, Westerdahl reports (see Figure 2). Thickness ranges from 4.7mm to 12.7mm armor plate. Producing MRAP parts involves what Westerdahl calls “dynamic etching,” or laser etching, each MRAP part for traceability.

“This can be a monumental programming task, because every individual part has to have the plate heat number etched on it. Since every plate has a unique heat number, the programming for every plate is different,” he says, citing the development of custom software tools to assist in the task.

Processing armor parts for the DoD also requires cutting and retention of test coupons both for metallurgical testing and traceability, which Service Steel also provides. “The metallurgical tests have to prove the armor plates are retaining their hardness, which can be affected by thermal cutting processes,” he says.

The company’s lasers provide quality parts, and its processing and material-handling capacity mean it can address the volume and schedule the government demands, but Westerdahl recognizes the need to look forward and adapt this experience to Service Steel’s future.

“Our company has stepped up several levels as a result of this experience,” he says. “We can handle and process 8 x 24-foot plates, which are less expensive for mills to produce. With the increase in steel prices, if you can handle larger plates, you can offer better plate usage efficiency. And lead time matters—when customers want it now, they know where to go.”

Westerdahl adds that the latest laser developments also factor in plate processing. “We’re running 24 hours a day, constantly doing heavy-duty cutting,” he says. “The new controlled-pulse piercing (CPP) from Bystronic really makes a difference compared to blast piercing—much less clean up and shorter overall cutting cycle times.

“In addition, Bystronic’s new pulse-cutting technologies allow us to cut much smaller holes. For example, we process three-eighths-inch plate requiring three-sixteenths holes that need to be tapped. These new pulse-cut holes go straight to tapping now without any post-processing cleanup or drilling. Before we would break taps every time we laser cut holes that small.”

Westerdahl and all his employees can take pride that his work is making a real difference. In June 2008, USA Today reported that not only fatalities, but also roadside bomb attacks in Iraq were down 90% from former levels, partially due to the thousands of MRAPs now deployed. While forces intent on doing harm can always adjust their tactics, it’s heartening to know that processing technology plays a large part in the response.

This case study is presented courtesy of Bystronic Inc., Hauppauge, NY, www.bystronicusa.com.