Ultrafast Lasers: Trends in femtosecond amplifiers—Ti:sapphire vs. ytterbium

Amplified femtosecond laser pulses enable many diverse applications because their high peak power (electric field) and very short pulses produce highly nonlinear processes and exquisite temporal resolution. For many years, titanium sapphire (Ti:sapphire) was the unanimous gain material of choice for ultrafast oscillator/amplifier systems. Recently, ytterbium (Yb) doped crystals, and particularly fibers, have been used in a growing range of femtosecond amplifiers with quite different (that is, complementary) performance characteristics in terms of pulse energy and average power. This article gives an overview of the current state of both technologies and their applications, showing how the scaling flexibility of Yb is now beginning to close the performance gap between the two technologies and impact the traditional domains of Ti:sapphire technology.

Ti:sapphire amplifiers

The high gain of Ti:sapphire crystals results in amplifiers that are unrivaled at delivering the highest pulse energies and shortest pulse durations at the lowest price per millijoule. By using two stages of amplification—typically a regenerative amplifier followed by a single-pass amplifier—it is possible to reach >13 mJ at 1 kHz with a commercial amplifier such as the Legend Elite HE+ series from Coherent, without resorting to cryogenic cooling. Indeed, the limiting design factor in kilohertz Ti:sapphire amplifiers is heat extraction from the gain crystal and the relatively short lifetime of the upper laser level. This means that these millijoule/pulse amplifiers need to be thermoelectrically (TE) or water-cooled and operate best at average power levels in the 7–15 W range and 1–10 kHz repetition rates. Combining these high pulse energies with pulse durations as short as 25 fs results in a peak power of hundreds of gigawatts.

Ti:sapphire is now a mature amplifier technology, so new models are usually characterized by incremental improvements in output specifications like power or carrier envelope phase (CEP) stability, with continuing effort to increase reliability, environmental stability, and maintenance intervals, especially in the case of so-called one-box versions. Although Ti:sapphire is tunable in the 700–1080 nm range, amplifiers are typically designed for optimized operation near the 800 nm peak of the tuning curve and broad tunability is achieved by pumping one or more tunable optical parametric amplifiers (OPAs).

Applications using Ti:sapphire amplifiers

The unique combination of high pulse energy, short pulse width, and high peak power from Ti:sapphire amplifiers has enabled diverse applications in physics, chemistry, biology, and material sciences. One of the most sophisticated applications is attosecond physics, where high harmonic generation (HHG) is used to create ultrabroadband pulses at extreme-ultraviolet (XUV) wavelengths that can be compressed to produce isolated attosecond-scale pulses when the optical carrier is locked to the pulse envelope (CEP stabilization).

At the other end of the electromagnetic spectrum, Ti:sapphire amplifiers are well suited to generating terahertz pulses. These can be used, for example, to interrogate semiconductor materials. In integrated circuits, transient electric fields can reach tens of megavolts per centimeter. Solid-state physicists want to know how fundamental charge transport mechanisms vary at fields of this magnitude and higher. Typical breakdown fields for many semiconductor materials are around 1 MV/cm—therefore, failure (burning) will rapidly occur if higher static fields are applied to test these materials. One solution that enables even higher fields to be safely applied is to use subpicosecond terahertz pulses.

In the laboratory of professor Rupert Huber at the University of Regensburg (Regensburg, Germany), a high-stability Ti:sapphire amplifier has been used to pump two tunable OPAs with a terahertz wavenumber difference in their outputs to create terahertz pulses with inherent CEP stability. These are used to probe the behavior (including Bloch oscillations) of electrons in gallium selenide samples under the influence of resultant transient fields approaching 100 MV/cm. By electro-optical “stroboscopic” gating of the signal from the sample with an 8 fs probe pulse at the terahertz detector, the data yields important information about Bloch oscillations as well as coherent and interfering conductive mechanisms only revealed at these high fields and short time intervals.

Another area where Ti:sapphire amplifiers are increasingly used is 2D spectroscopy, where the optical signal (emission, harmonic conversion, etc.) from a sample is recorded as a function of the wavenumber of an ultrabroadband pulse from an OPA, providing a unique combination of structural and dynamic data (see Fig. 1). Most 2D spectroscopy measurements are made in the time domain and converted to the frequency domain using Fourier-transform (FT) algorithms. Instead of using light at one frequency, ultrafast pulses of broadband light are used so that all frequencies are recorded simultaneously.

The operational simplicity and stability of one-box Ti:sapphire amplifiers such as the Coherent Astrella are proving ideal for these type of experiments that are relatively complex and require data acquisition times measured in hours and days. For example, in the laboratory of Graham Fleming (University of California, Berkeley), scientists are using 2D spectroscopy to probe the fundamental physics in perovskite films that might be used in next-generation solar cells. In the laboratory of Wei Xiong (University of California, San Diego), researchers are using a unique type of 2D spectroscopy to study a CO2 reduction catalyst expected to be important for artificial photosynthesis.

Ytterbium amplifiers and applications

While Ti:sapphire amplifiers are a mature technology, Yb is more than 15 years younger and therefore more dynamic in terms of performance improvements. Unlike Ti:sapphire, Yb can also be used as a dopant in gain fibers that enable the thermal load from the optical pumping to be spread over a longer path with much larger surface area/volume. Even when used as a dopant in bulk material, this reduced thermal sensitivity for the lasing properties of Yb enables higher pumping average power compared to Ti:sapphire, and does not require cryogenic cooling.

In addition, the much better quantum defect (980 nm pumping/1040 nm lasing for Yb vs. 532 nm pumping/800 nm lasing for Ti:sapphire) means that less energy is wasted as heat. Finally, pump power from diodes at 980 nm is less expensive than from a diode-pumped laser at 532 nm. Consequently, Yb can be scaled to much higher average powers with a lower cost per watt, compared to Ti:sapphire amplifiers. In fact, Yb amplifiers can deliver tens of watts from the footprint the size of a desktop computer.

Despite advances in average power, typical Yb amplifiers are limited to pulse outputs of a few millijoules in the femtosecond regime and cannot reach the 10 mJ-class pulse outputs offered by Ti:sapphire amplifiers. Yb fiber systems face a limitation due to peak power inside very small fiber cores, while Yb bulk systems typically face a tradeoff between achievable energy and pulse duration.

The gain bandwidth in Yb is not as broad as in Ti:sapphire, so its pulses are naturally longer. Therefore, recompression after chirped-pulse amplification (CPA) in bulk (or natural dispersion in fibers) results in pulse widths around 250 to 300 fs. While this is short enough for many applications, it does not match the temporal resolution (and spectral bandwidth) of Ti:sapphire amplifiers used for pump-probe, 2D spectroscopy, and similar time-resolved experiments. There are, however, several ways to overcome this limitation.

Like Ti:sapphire amplifiers, Yb systems require an OPA to enable wavelength tuning. By using a hybrid design, the OPA greatly reduces the resulting pulse width while maintaining a useful tuning range. Such an OPA includes a noncollinear stage to generate pulse widths as short as 40 to 50 fs, followed by a high-power collinear stage which delivers very broad wavelength tuning.

The compact architecture of Yb amplifiers lends itself to additional improvements in the overall amplified tunable system. For example, the White Dwarf optical parametric chirped-pulse amplifier (OPCPA) from Class 5 Photonics (Hamburg, Germany) incorporates a Coherent Monaco Yb-fiber amplifier and the OPCPA together in a single, compact box. With this approach, the OPCPA extends the performance of Yb-based systems into the ultrashort (less than 9 fs) pulse regime as well as the broadly tunable regime with approximately 50 fs pulse duration, providing highly customizable performance in a single box.

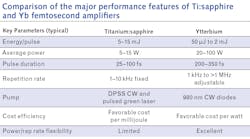

This all means that researchers now have a choice between two high-performance technologies, Ti:sapphire and Yb (see table). Currently, the high, flexible repetition rates and high power of Yb amplifiers mean they are now being adopted in numerous ultrafast applications, with the exception of techniques that still need the uniquely high pulse energy and peak power of Ti:sapphire. These Yb applications tend to fall into two categories.At repetition rates of 50 to 250 kHz, they are used for pump-probe and transient absorption spectroscopy studies. The higher repetition rate, compared to Ti:sapphire, means faster data acquisition times and better signal-to-noise data. This is especially true in the case of solid-state material studies, where the electronic dynamics involved are very fast and sample excitation requires only moderate energies. Examples include 2D materials such as graphene, quantum dots, nanoparticles, and metamaterials with custom photonic properties, as well as studies of ambient temperature semiconductors and novel photovoltaics. However, it should be noted that numerous experiments in liquid and gas phase, especially in the mid-infrared, require energies that can be provided only by Ti:sapphire lasers at 1 to 5 kHz, where the low repetition rate is dictated by the sample recovery or system acquisition rate.

Yb applications requiring this type of laser’s unique 1–10 MHz capabilities involve imaging techniques such as three-photon microscopy for deep brain imaging in neuroscience and two-photon optogenetics. These repetition rates are fundamentally required by the image scanning process. For conventional raster scanning, most multiphoton microscopes operate with a 512 × 512 imaging field, or 262,000 pixels. To operate at a few-hertz image refresh rate with more than a few pulses per pixel requires megahertz rates. Even higher speeds are needed for video-rate imaging.

As an example, a team led by Jack Waters at the Allen Institute (Seattle, WA) is using a Yb amplifier/OPA combination to study the communication between cholinergic neurons and the cortical network. Cholinergic neurons are neurons that release acetylcholine to signal with other networks. They are located in deeper nuclei in the brain and project their axons into the cortex. They use three-photon excitation of calcium indicators excited at 1300 nm. This long wavelength not only scatters less in brain tissue, but it can penetrate the mouse cranium (see Fig. 2), eliminating the need for a glass window that restricts the field of view, hampering studies that may target global effects in the mouse cortex.Bridging the performance gap

The most recent development in ultrafast amplifiers exploits the flexibility of Yb and targets the performance gap between typical Yb and Ti:sapphire amplifiers—that is, generating both high pulse energy and high repetition rates. An example is the Monaco HE from Coherent, which delivers 25 W of average power with repetition rates up to 250 kHz. At or below 10 kHz, this type of amplifier can deliver 2 mJ/pulse in a small one-box architecture. For comparison, a 20 W, 10 kHz Ti:sapphire amplifier would require cryocooling and 40 square feet of tabletop space.

A number of applications that previously used Ti:sapphire amplifiers are expected to benefit from this new operating regime and its intrinsic flexibility. Examples include multidimensional and time-resolved spectroscopy, terahertz spectroscopy, and photoelectron emission spectroscopy of solid-state samples. These will all benefit from the faster data accumulation enabled by moving from the kilohertz regime to hundreds of kilohertz. At the same time, flexibility in repetition rate enables studying different types of samples using a single ultrafast laser system with one or two OPAs.

The operating regime of ultrafast laser amplifiers is at the pinnacle of scientific laser technology—cutting-edge laser performance supporting exciting cutting-edge science. It’s now nearly 35 years since the Nobel-winning research of Gérard Mourou and Donna Strickland crucially demonstrated CPA of ultrafast pulses, but developments in ultrafast amplifiers and applications show no signs of slowing down any time soon.

About the Author

Marco Arrigoni

Marco Arrigoni is vice president of marketing at Light Conversion (Vilnius, Lithuania). He previously served as director of marketing at Coherent (Santa Clara, CA) from 2007 through 2023.

Steve Butcher

Scientific Marketing Manager, Coherent

Steve Butcher is scientific marketing manager at Coherent (Santa Clara, CA).

Joseph Henrich

Senior Product Line Manager, Coherent

Joseph Henrich is senior product line manager at Coherent (Santa Clara, CA).

![FIGURE 2. Calcium imaging is done through an intact mouse skull, where (a) shows a schematic of preparation without acrylic or coverslip, (b) shows temporal mean projection from a Emx1-IRES-Cre;CaMk2a-tTA;Ai94 mouse (10 Hz frame rate, 3P excitation at 1300 nm through intact skull, ~300 µm thick, microscope focused 450 µm below pia.), and (c) spontaneous calcium transients from GCaMP-expressing somata (circles in panel [b]). FIGURE 2. Calcium imaging is done through an intact mouse skull, where (a) shows a schematic of preparation without acrylic or coverslip, (b) shows temporal mean projection from a Emx1-IRES-Cre;CaMk2a-tTA;Ai94 mouse (10 Hz frame rate, 3P excitation at 1300 nm through intact skull, ~300 µm thick, microscope focused 450 µm below pia.), and (c) spontaneous calcium transients from GCaMP-expressing somata (circles in panel [b]).](https://img.laserfocusworld.com/files/base/ebm/lfw/image/2020/02/2002LFW_arr_f2.5e3ad703a013d.png?auto=format,compress&fit=max&q=45?w=250&width=250)