Diamond Brillouin laser could generate millimeter-wave frequencies for radar

Researchers from Macquarie University (Macquarie Park, Australia) have discovered a novel and practical approach to Brillouin lasers (lasers that incorporate light/sound interaction for light amplification), in the form of diamond lasers that have an output power 10X higher than any other Brillouin laser. Diamond is a particularly interesting material for this type of laser: Its high thermal conductivity makes it possible to create miniature lasers that simultaneously have high stability and high power; in addition, the speed of sound in diamond (18 km/s) is also much higher than in other materials, giving the laser a secondary ability to directly synthesize frequencies in the hard-to-reach millimeter-wave band (30–300 GHz) via photomixing. Brillouin laser synthesis of these frequencies is important because there is an intrinsic mechanism that reduces the frequency noise to the levels needed by next-generation radar and wireless communication systems. This has been a major challenge for electronics or other photonic-based generation schemes.

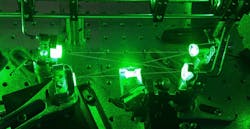

The new laser, the first bench-top Brillouin laser that uses diamond, provides a practical approach to Brillouin lasers with an increased range of performance. In contrast to earlier Brillouin lasers, the diamond version operates without having to confine the optical or sound waves in a waveguide to enhance the interaction. As a result, these lasers can be more easily scaled in size and have greater flexibility for controlling the laser properties as well as increasing power. Only a very small amount of waste energy is deposited in the diamond sound-carrying material, which leads to features including beam generation with ultrapure and stable output frequency, the generation of new frequencies, and potentially, lasers with exceptionally high efficiency. The diamond Brillouin laser produces more than 10 W of optical power and demonstrated a synthesized 167 GHz from a 532 nm input. The authors next want to demonstrate lasers with the higher levels of frequency purity and power needed to support future progress in quantum science, wireless communications, and sensing. Other applications include ultrasensitive detection of gravitational waves and manipulating large arrays of qubits in quantum computers. Reference: Z. Bai et al., Appl. Phys. Lett. Photonics, 5, 031301 (2020); https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5134907.

John Wallace | Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.