Silicon-photonic photon source is near-ideal for quantum-optical technologies

Integrated quantum photonics is a promising platform for developing quantum technologies, including quantum computers, due to its capacity to generate and control individual photons in its optical circuits. However, an important challenge that has limited the scaling of integrated quantum photonics has been the lack of on-chip sources able to generate high-quality single photons, according to Stefano Paesani, one of a team of physicists at the University of Bristol (England) working on quantum photon sources. “Without low-noise photon sources, errors in a quantum computation accumulate rapidly when increasing the circuit complexity, resulting in the computation being no longer reliable,” says Paesani. “Moreover, optical losses in the sources limit the number of photons the quantum computer can produce and process.”

Together with colleagues at the University of Trento in Italy, the Bristol team has developed the first integrated photon source compatible with large-scale quantum photonics.1 The source is based on a novel technique called intermodal spontaneous four-wave mixing (SWFM), in which multiple modes of light propagating through a silicon waveguide are nonlinearly interfered, creating ideal conditions for generating single photons.

In SWFM, light from a laser can be converted into pairs of single photons as long as phase-matching and energy conservation conditions are met. However, standard SWFM produces photons with a strong spectral anticorrelation, which is the opposite of what is needed in quantum optics circuits. In contrast, intermodal SWFM suppresses these spectral anticorrelations by exciting two optical modes in a waveguide—here, TM0 and TM1—that are phase-matched with respect to each other and therefore can produce pairs of single photons without the anticorrelation. The waveguide cross-section must be specially tailored so that the phase-matching bandwidth is similar to the pump-laser bandwidth, which leads to the required energy conservation.

Two different modes interfering

In the experiment, idler photons were generated in the TM0 mode at a 1516 nm wavelength, and signal photons in the TM1 mode at 1588 nm with the pump-laser/phase-matched bandwidth being about 4 nm. A gradually increasing time delay in the TM0 portion of the pump-laser light suppresses spurious spectral correlations, resulting in a spectral purity of 99.4%, rather than the 84% expected without the time delay.

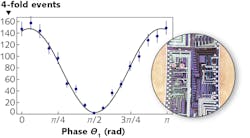

The team benchmarked the use of such sources for photonic quantum computing in a so-called heralded Hong-Ou-Mandel experiment (see figure), which quantifies the interference of photons heralded from different sources and is a building block of optical quantum information processing, and obtained the highest-quality on-chip photonic quantum interference ever observed of 96% visibility. According to Paesani, the device demonstrated by far the best performances for any integrated photon source: a spectral purity and indistinguishability of 99% and greater than 90% photon-heralding efficiency.

The silicon photonic device was fabricated via CMOS-compatible processes in a commercial foundry; as a result, thousands of sources could be easily integrated on a single device. “Arrays of hundreds of these sources can be used to build near-term noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) photonic machines, where tens of photons can be processed to solve specialized tasks such as the simulation of molecular dynamics or certain optimization problems related to graph theory,” says Paesani, who notes that the technology could lead to fault-tolerant quantum operations in an integrated photonics platform.

In the next few months, tens to hundreds of the quantum sources will be integrated on a single chip.

REFERENCE

1. S. Paesani et al., Nat. Commun. (2020); https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16187-8.

John Wallace | Senior Technical Editor (1998-2022)

John Wallace was with Laser Focus World for nearly 25 years, retiring in late June 2022. He obtained a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering and physics at Rutgers University and a master's in optical engineering at the University of Rochester. Before becoming an editor, John worked as an engineer at RCA, Exxon, Eastman Kodak, and GCA Corporation.