Conversion of abundant, common carbon into bulk diamond is typically accomplished through volcanic action or laboratory environments at very high temperatures and pressures, while diamond thin films require chemical vapor deposition (CVD) processes at moderate temperatures in the presence of hydrogen. But an alternate method from researchers at North Carolina State University (Raleigh, NC) converts amorphous carbon films to a new state of carbon called Q-carbon through irradiation with a 193 nm argon fluoride (ArF) excimer laser pulse, with photon energy of 6 eV and pulse duration of 20 ns.

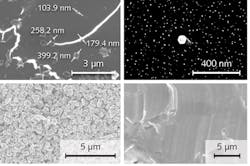

After illumination with 0.6 J/cm2 pulses from the laser, a variety of different diamond forms is possible depending upon exposure times and pulse frequency, including nanodiamonds, microdiamonds, mixtures of nano- and microdiamonds, and large-area single-crystal diamond thin films on metal/semiconducting epitaxial substrates. Using this nanosecond pulsed laser melting approach, the researchers can also create nano- and microneedle diamonds for biomedical applications. The Q-carbon forms are not only fabricated at ambient temperatures without catalysts or gases, but also have unique chemical properties such as room-temperature ferromagnetism and enhanced hardness, field emission, and electrical conductivity. Reference: J. Narayan and A. Bhaumik, J. Appl. Phys., 118, 21, 215303 (Dec. 2015).

About the Author

Gail Overton

Senior Editor (2004-2020)

Gail has more than 30 years of engineering, marketing, product management, and editorial experience in the photonics and optical communications industry. Before joining the staff at Laser Focus World in 2004, she held many product management and product marketing roles in the fiber-optics industry, most notably at Hughes (El Segundo, CA), GTE Labs (Waltham, MA), Corning (Corning, NY), Photon Kinetics (Beaverton, OR), and Newport Corporation (Irvine, CA). During her marketing career, Gail published articles in WDM Solutions and Sensors magazine and traveled internationally to conduct product and sales training. Gail received her BS degree in physics, with an emphasis in optics, from San Diego State University in San Diego, CA in May 1986.