Ultrashort laser pulses let glass take on metallic properties

Confirmed by calculations at the Vienna University of Technology (TU Vienna; Vienna, Austria), quartz glass can take on metallic properties for tiny fractions of a second when illuminated by an ultrafast laser pulse. The effect could be used to build logical switches that operate much faster than today’s microelectronics.

RELATED ARTICLE: Advanced synchronization techniques enable novel ultrafast science

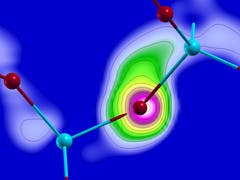

Quartz glass does not conduct electric current as it is a typical example of an insulator. With ultrashort laser pulses, however, the electronic properties of glass can be fundamentally changed within femtoseconds and if the laser pulse is strong enough, the electrons in the material can move freely. For a brief moment, the quartz glass behaves like metal. It becomes opaque and conducts electricity. This change of material properties happens so quickly that it can be used for ultrafast-light-based electronics. Scientists at the TU Wien have now managed to explain this effect using large-scale computer simulations.

In recent years, ultrashort or ultrafast laser pulses of only a few femtoseconds have been used to investigate quantum effects in atoms or molecules. Now they can also be used to change material properties. In an experiment (at the Max-Planck Institute in Garching, Germany) electric current has been measured in quartz glass, while it was illuminated by a laser pulse. After the pulse, the material almost immediately returns to its previous state. Georg Wachter, Christoph Lemell, and professor Joachim Burgdörfer (TU Wien) have now managed to explain this peculiar effect in collaboration with researchers from the Tsukuba University in Japan.

Quantum mechanically, an electron can occupy different states in a solid material. It can be tightly bound to one particular atom or it can occupy a state of higher energy in which it can move between atoms. This is similar to the behavior of a little ball on a dented surface: when it has little energy, it remains in one of the dents. If the ball is kicked hard enough, it can move around freely.

"The laser pulse is an extremely strong electric field, which has the power to dramatically change the electronic states in the quartz," says Georg Wachter. "The pulse can not only transfer energy to the electrons, it completely distorts the whole structure of possible electron states in the material."

That way, an electron that used to be bound to an oxygen atom in the quartz glass can suddenly change over to another atom and behave almost like a free electron in a metal. Once the laser pulse has separated electrons from the atoms, the electric field of the pulse can drive the electrons in one direction, so that electric current starts to flow. Extremely strong laser pulses can cause a current that persists for a while, even after the pulse has faded out.

"Modelling such effects is an extremely complex task, because many quantum processes have to be taken into account simultaneously," says Joachim Burgdörfer. The electronic structure of the material, the laser-electron interaction and also the interactions between the electrons has to be calculated with supercomputers. "In our computer simulations, we can study the time evolution in slow motion and see what is actually happening in the material," says Burgdörfer.

In the transistors we are using today, a large number of charge carriers moves during each switching operation, until a new equilibrium state is reached, and this takes some time. The situation is quite different when the material properties are changed by the laser pulse. Here, the switching process results from the change of the electronic structure and the ionization of atoms. "These effects are among the fastest known processes in solid state physics," says Christoph Lemell. Transistors usually work on a time scale of picoseconds, whereas laser pulses could switch electric currents a thousand times faster.

The calculations show that the crystal structure and chemical bonds in the material have a remarkably big influence on the ultrafast current. Therefore, experiments with different materials will be carried out to see how the effect can be used even more efficiently.

SOURCE: Vienna University of Technology; http://www.tuwien.ac.at/en/news/news_detail/article/8955/

Gail Overton | Senior Editor (2004-2020)

Gail has more than 30 years of engineering, marketing, product management, and editorial experience in the photonics and optical communications industry. Before joining the staff at Laser Focus World in 2004, she held many product management and product marketing roles in the fiber-optics industry, most notably at Hughes (El Segundo, CA), GTE Labs (Waltham, MA), Corning (Corning, NY), Photon Kinetics (Beaverton, OR), and Newport Corporation (Irvine, CA). During her marketing career, Gail published articles in WDM Solutions and Sensors magazine and traveled internationally to conduct product and sales training. Gail received her BS degree in physics, with an emphasis in optics, from San Diego State University in San Diego, CA in May 1986.