Graphene has been hailed a “wonder material,” given its potential in a growing pool of applications and industries, from quantum computing (also see “Getting edgy with graphene”) to healthcare. But it’s also a bit unassuming. While it’s the thinnest material in the world at just one atom-thick, graphene is among the strongest at roughly 200X stronger than steel.

A monolayer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice, graphene’s most common use has been to form graphite, which is comprised of stacked graphene layers held together by van der Waals forces—essentially the backbone of pencils and lubricants. Moving beyond those historical uses, graphene is advancing into a jack of all trades.

Let’s take a look at how researchers are finding exciting new uses for this wonder material.

Gas sensors

As its potential applications escalate, graphene is playing a pivotal role in enhancing chemical sensors and imagers. Graphene-based sensors work by measuring alterations in the electrical conductivity of the material, and also by absorbing a gas molecule on the graphene’s surface, which acts as donors or acceptors of electrons. The benchmarked parameters of graphene sensors include sensitivity, selectivity, response and recovery time, and detection limit.

According to the Graphene Council, scientists have found that the material can measure quantum-scale changes in conduction. It “boasts the benefit of being an extremely low-noise material. Because of this, even at the limit of no carriers and a few extra electrons, graphene’s carrier concentration is able to change considerably.” Additionally, graphene enables the creation of four-probe devices on monocrystals, basically guaranteeing eradication of “any influence of the contact resistance in limiting sensitivity.”

Healthcare, biomedical research

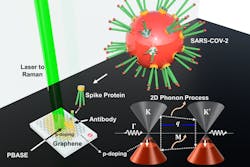

Promising results from lab experiments at the University of Illinois Chicago show that a graphene-based sensor can quickly spot COVID-19 (see figure). Published in ACS Nano, the research involved “modification of the dopant density and the phononic energy of antibody-coupled graphene when it interfaces with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.”

Researchers created the sensor by combining sheets of graphene and an antibody developed to target the spike protein. Using a Raman spectrometer, they measured the sheets’ atomic-level vibrations after exposing them to samples of artificial saliva that were COVID-positive and others that were COVID-negative. Those vibrations changed when they treated it with the positive sample; there was no change with the negative sample—the changes became evident in less than 5 minutes.

According to the study, the graphene chemeo-phononic system identified the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein at a detection limit of about 3.75 fg (force exerted by gravitation) per milliliter in artificial saliva, and about 1 fg (force exerted by gravitation) per milliliter in phosphate-buffered saline. “It also exhibited selectivity over proteins in saliva and MERS-CoV spike protein. Since the change in graphene phononics is monitored instead of the phononic signature of the analyte, this optical platform can be replicated for other COVID variants and specific-binding-based bio-detection applications.”

The researchers note that carbon atoms in graphene are bound by chemical bonds, the elasticity and movement of which can produce resonant vibrations (phonons—the “collective excitation in a periodic, elastic arrangement of atoms or molecules in condensed matter”). This leads to very accurate measurements. When the SARS-CoV-2 molecule interacted with graphene, those resonant vibrations changed “in a quantifiable way.”

The promising takeaway is that the potential for early detection of future variants could lead to earlier, quicker administration of treatments and a higher rate of successful recovery.

Dentistry

Graphene is also employed in dentistry-related studies, as well as some procedures. In research published in Applied Materials Today, a team at Okayama University in Japan has found that graphene oxide (GO, a graphene nanomaterial) and functionalized GO “has provided outstanding results in antimicrobial action, regenerative dentistry, bone tissue engineering, drug delivery, physicomechanical property enhancement of dental biomaterials, and oral cancer treatment.” Graphene nanomaterials have exhibited unique optical, mechanical, and physiochemical properties that are specifically benefitting dental research. Overall, the researchers note, GO has a number of “chemically reactive functional groups on its surface, which facilitate interaction with DNA, proteins, polymers, and biomolecules” and shows great promise for biomedicine.

Across multiple studies, the researchers have developed GO for “biofilm and caries prevention as well as implant surface modification and as a quorum sensing inhibitor,” thanks to graphene’s antibiofilm and antiadhesion properties.

Specifically, graphene has proven beneficial for tissue engineering for treatments such as restoration of missing teeth. While most artificial biomaterials such as collagen lack “tissue-inductive activities,” scaffolds created using GO have prompted bone formation five times faster than has been possible with collagen scaffolds.

There’s promise for dental implants as well with graphene helping address the issue of leaking seals at the hard and soft tissue interfaces, which often leads to bacterial infections. In an AZO Materials contribution, biotechnology researcher Dr. Priyom Bose said, “the healing process must be accelerated and bacterial colonization must be prevented. When graphene is coated with titanium substrate, its hydrophobic character imparts a self-cleaning effect on its surfaces, which enables a reduction in the adhesion of dental pathogens.”

Endodontic procedures such as root canals involve bioactive cement for the management of perforation, pulp capping, and retrograde root filling. Bose notes that graphene nanosheets improve the mechanical property of the bioactive cement.” For restorative dentistry and periodontology (the study of teeth’s supporting structures as well as diseases and conditions that affect them), fluoride graphene boosts the mechanical and antibacterial properties of glass ionomers, which are commonly used in restorative dentistry. It also “decreases microcracks in the internal structure and protects it from erosion and disintegration by microbial invasion.”

Quantum computing

A team at Nagoya University in Japan has been dabbling in graphene, with a biomedical tie but for the purpose of potentially advancing the next generation of quantum computing. The researchers developed this technique as the human brain can process highly complex data (such as images) more efficiently than existing computer architectures with limited processing speeds.

The team has designed graphene/diamond junctions that mimic the characteristics of biological synapses as well as key memory functions. In a study published in Carbon, they demonstrated “optoelectronically controlled synaptic functions using junctions between vertically aligned graphene and diamond.” The junctions essentially mimic biological synaptic functions, “such as the production of ‘excitatory postsynaptic current’”—the charge induced by neurotransmitters at the synaptic membrane—when they stimulated it by optical pulses. They were also found to exhibit other basic brain functions, including the transition from short-term to long-term memory.

“Our brains are well equipped to sieve through the information available and store what's important,” says Dr. Kenji Ueda, a researcher in the Department of Materials Physics at Nagoya who led this study. “We tried something similar with our [vertically aligned graphene and diamond] arrays, which emulate the human brain when exposed to optical stimuli. This study was triggered due to a discovery in 2016, when we found a large optically induced conductivity change in graphene-diamond junctions.”

Udea adds that this study offers a better understanding of “the working mechanism behind the artificial optoelectronic synaptic behaviors, paving the way for optically controllable brain-mimicking computers and better information-processing capabilities than existing computers.”

Considering these existing applications—and the continued interest in further research—it is easy to understand how graphene is truly becoming the wonder material.

Getting edgy with graphene

The next generation of devices is right around the corner—and we have a new phase of graphene to thank.

A team at Purdue University (West Lafayette, IN) has demonstrated that graphene’s viscous fluid can boost unidirectional electromagnetic “edge waves,” which are “linked to a new topological phase of matter and symbolize a phase transition in the material. With this, light travels in only one direction along the edge of the graphene material, making it “robust to disorder, imperfections, and deformation.”

The researchers used graphene because of its electrical conduction properties.

All of this has the potential to boost all-optical processing, as well as quantum information processing, computing, and networking, and interconnects between quantum and classical computing systems.

“There is a lot of interest right now in trying to build interconnections between our quantum systems and classical systems,” says researcher Zubin Jacob, the Elmore associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at Purdue; he worked alongside postdoctoral researcher Todd Van Mechelen and graduate research assistant Wenbo Sun on this study. “[Quantum systems] are basically information processing nodes that can beat classical systems. These [quantum systems] are the next generation of devices we are going to have.”

He notes, however, that quantum systems are very complex and may not be able to stand on their own. “They will need to be interfaced with existing supercomputers and hardware systems to communicate information in one direction back and forth.” Basically, “you want the information to preferentially flow in whichever direction you want.” Interconnects and a topological circulator device (cylindrical one-way signal routers developed by the Purdue team) allow this (see figure), unlike an isolator, which isolates the signal in one direction but not the other.

“Instead of just two systems, like A and B, just think of three ports: one, two, and three,” Jacob says. “So, you're interfacing three signals in your cell phone or three antennas, for example, and so forth. That's our circulator. You want information to go from one to two, two to three, and three to one, but not the other way around. The information circulates between whichever routes you choose, but not the other way around.”

Topological circulators are crucial devices for a variety of systems, and show potential for on-chip, all-optical processing because they are “a fundamental building block in integrated optical circuits.” However, they are large and bulky, whereas the processing chip is very small. This presents a problem, according to the researchers.

“We can’t fit hundreds of thousands of them on a small chip,” Jacob says. “We are trying to really miniaturize all of this. And the idea is we need signals to go from one port to another, but not backward. But this is very difficult to achieve if your system is really small. If you wanted a future device where you needed these circulators jam-packed on the chip, you want to make it really small. This is not possible because these devices require a magnetic field, a large and bulky magnet, and large cables to be routing the signal. And these signals are generally electromagnetic signals.”

He adds that his team, in searching for new approaches to shrinking the topological circulators, realized that the secret is charge plus electron fluid plus Hall viscosity—it is the electron fluid and graphene that are charged. This presents a special (new) viscosity that is not related to friction. “Instead of causing energy to dissipate, friction means there’s some heating going on; there is some dissipation going on. This is special because there is no dissipation associated with [Hall viscosity].”

“What we have shown is that it is indeed possible to rethink how these devices work, and approach this technology in a different way,” Jacob says, “and actually make it 10X or 100X smaller than what exists today.”

About the Author

Justine Murphy

Multimedia Director, Digital Infrastructure

Justine Murphy is the multimedia director for Endeavor Business Media's Digital Infrastructure Group. She is a multiple award-winning writer and editor with more 20 years of experience in newspaper publishing as well as public relations, marketing, and communications. For nearly 10 years, she has covered all facets of the optics and photonics industry as an editor, writer, web news anchor, and podcast host for an internationally reaching magazine publishing company. Her work has earned accolades from the New England Press Association as well as the SIIA/Jesse H. Neal Awards. She received a B.A. from the Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts.