CONCENTRIC OPTICS: Catadioptric camera lens is broad-spectrum

When New Zealand scientist David Beach attempted to photograph Halley`s Comet from his home in the late 1980s and failed, he inadvertently developed what some call the world`s most powerful photographic lens. With just a handful of systems built so far, the scalable, high-resolution, broad-spectrum catadioptric-lens-design system has potential applications ranging from astronomy to surveillance. On a clear night, KiwiStar can provide a good picture of nebulae and galaxies or photograph a car license plate from a half mile away.

Use of concentric spherical optical systems to reduce or eliminate off-axis aberrations has been understood for many decades, as has been use of focal reducers to achieve higher-numerical-aperture values in otherwise slow optics.

To develop his imaging system, Beach, a physicist at Industrial Research Ltd. (Auckland, New Zealand), joined two lenses with exceptionally good wide-angle properties to produce an even more powerful lens that works in dim light at long range. The resulting images are completely free of coma and astigmatism. The concentric-optics system is most effective when attached to a solid-state imaging detector, producing an effect somewhat like that of an ultrasensitive video camera. Beach estimates it is possible to build a simplified version of the imaging system for around $10,000.

More specifically, by optically coupling the concentricities of a primary catoptric and a focal reducer catadioptric, Beach produced an imaging system that has significant gain over conventional designs in combined image illuminance, resolution, and spectral bandwidth. Suited to aperture diameters of 100 mm to greater than 2 m with the right electronic detector, the system permits near-zero values for all the classical Seidel aberrations at relative apertures faster than f/1, with field angles of up to 7° arc, a 600-nm bandwidth in the visible and near-infrared, and zero vignetting. Performance is limited only by high-order aberrations.

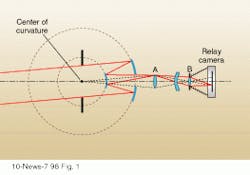

The KiwiStar concept has four essential optical components (see Fig. 1). Refractive components are subdiameter, and only the spherical primary mirror is of full-aperture diameter. One advantage of the system is that the entrance-pupil diameter is not limited by the availability of homogeneous refractive materials. In addition, a relatively small meniscus lens close to the focal-reducing camera module handles spherical-aberration correction of the primary and Cassegrain secondary mirror, while the entrance-pupil diameter is related only to the size of the spherical primary mirror. There is no need for a primary-system aperture stop because this function is carried out by the aperture stop of the focal-reducing camera, which is the marginal ray delimiter. According to Beach, the instrument package can be fairly compact in some applications because system length is reduced by a distance equal to the separation of the entrance pupil and secondary mirror, and there are several opportunities for folding the optical train.

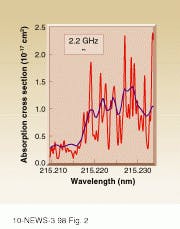

The KiwiStar prototype unit was based on the hardware of a Meade 10-in. Schmidt-Cassegrain astronomical telescope that had been optically modified, while retaining the original spherical primary mirror and tube structure. The Meade corrector was replaced with an optical-quality window to support the spherical secondary mirror, and an entirely new focal-reducer module based on a Hawkins and Linfoot camera was attached to the rear mirror cell. System specifications included F = 180 mm, f/0.9, 400-1100-nm bandwidth, and an angular field of 2.2 × 2.9° on a 7 × 9-mm charge-coupled-device chip.Prototype performance matched prediction and resulted in pixel-limited resolution over 75% of the 756 × 581-pixel array. Also of note was the reported ease of manufacture for both it and a subsequent system built for Los Alamos National Laboratory (Los Alamos, NM). According to Beach, required metal and optical components for various KiwiStar designs can be fabricated to normal engineering tolerances using standard techniques (see Fig. 2).

About the Author

Paula Noaker Powell

Senior Editor, Laser Focus World

Paula Noaker Powell was a senior editor for Laser Focus World.