A thriller movie script may read, "The spy slides the corpse off his back and places the dead man`s fingers in the hand reader. Seconds turn into minutes as the recognition system analyses the input. Finally, the security door to the nuclear-power generator opens. The agent glances anxiously around before slipping inside to dissect the bomb. . . ." In the make-believe world of James Bond, Arnold Schwarzenegger, and Harrison Ford, biometrics, or the automated use of a person`s body for identification, is a way of life. For the rest of us, such security systems still seem to be in the distant future.

However, a surprising number of biometric devices are already in use. From the expected high-level government security offices to jails, health clubs, dairy farms, office buildings, and private homes, more than 10,000 locations now require identification of a part of the body to walk in the door or access a file. This is just the beginning. The industry is expected to grow from $16 million in revenues in 1996 to $50 million in 1999, according to industry analysts.

Your finger, please

Fingerprinting is easily the most familiar of all recognition technologies. "The fingerprint will be the de facto standard [for biometrics]," predicts Keith Clemons of Mytec Technologies Inc. (Don Mills, Ont., Canada). "This is because it is already accepted by law-enforcement agencies worldwide. People know that no two fingerprints are exactly alike. It is the most easily accessed and most user-friendly."

Mytec has designed the Biometric Encryption process—a technology that uses a finger-pattern-coding process to scramble information. A person places his or her index finger on a prism. A low-power light-emitting diode (LED) scans the print. A charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera captures the scanned imaged and numerically digitizes it. Then, through a patented process, this information is scrambled along with other digital data such as an encryption key. The information stored in the scrambled template is now secure and can only be released through validation of the correct finger. Applications include the elimination of fraud associated with unauthorized use of health, welfare, credit, and financial services.

Uniqueness of hands

Hands are being used for identification, as well. "A hand reader is a funny-looking door knob," says Bill Spence of Recognition Systems (Campbell, CA), founded in 1986 to bring biometrics to the commercial market. There are more than 12,000 of the company`s ID-3D Handkey currently in use worldwide. The device "looks at the size and shape of your hand. We look at the length, width, thickness, and surface area of your fingers and part of your hand (see photo p. 109). If you crack your knuckles, we know about it. If you broke your finger at one time, we know about it," says Spence.

This technology uses a 32,000-pixel image array along with a set of 890-nm LEDs. The light is reflected off a mirror onto a reflective surface where the hand is placed. The returned image is digitized through a series of compressed algorithms. Ninety-six different measurements are taken. The image is similar to a shadow cast from a flashlight shining on a hand, says Spence, "but we see the shadow in three dimensions."

Most biometric systems take a complete image of the template and a complete image of the applicant and do an image overlay. The Handkey examines and stores only what makes one hand differ from all others. This makes the reference template the smallest in the industry, says Spence, utilizing only nine bytes of computer space.

Hand geometry is a very easy thing to get used to, says Spence. "The reality is that you will put your hand anywhere as long as you can see it." The most public demonstration of this technology was at the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, GA.

Another high-profile use of hand identification is the Fastgate program for immigration and border crossings. "This is particularly useful for frequent travelers," says Spence. "Instead of showing your passport and face you would go to a machine that looks like an automatic teller machine (ATM) that uses your hand to verify your identity." Currently, these machines are installed in New York, Newark, and Miami airports. Soon the Handkey will be added to airports in Boston, Chicago, Dallas, Los Angeles, and Honolulu, as well as many international airports.

Baby face

The first driver`s license facial-recognition system is scheduled for operation this month in West Virginia. The system, developed by Polaroid Corp. (Cambridge, MA), is intended to reduce the fraudulent reissue of licenses. The device relates key features on your face to other key features in a numerical pattern. The software maps an x-y graph using your nose as the center point, or zero, says Jeff Seideman of ImageTech Communications (Cambridge, MA). "The system has the ability to eliminate unnatural markings such as a scar," says Seideman. But it is also very forgiving. Changes in hair color, length, weight, age, or even cosmetic alterations are taken into consideration.

Yet the system is still sensitive enough to reject too many changes. In a pilot program, a woman who used her older sister`s information to obtain an illegal driver`s license was uncovered when the sister came to renew her license; although the two resembled each other visually, the biometric information in the computer database did not match.

Drivers in West Virginia will be required to supply a signature, fingerprint, and portrait, as well as have their picture taken with an electronic camera. Subsequent license renewal will compare current characteristics with the stored data. If a driver fails the facial comparison, as well as the fingerprint and signature contrast, a supervisor will make an "old-fashioned" visual comparison.

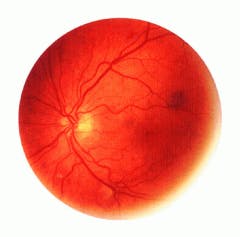

Eyes to the soul

Perhaps having even more distinctive characteristics than a fingerprint, facial feature, or hand is the retina, says Chad Cutrer of EyeDentify Inc. (Baton Rouge, LA; see Fig. 1). As the eye is developing, the blood-vessel pattern of the retina forms, holds the same stable environment as the brain, and stays constant over a lifetime. "It never changes, it can`t be altered like a fingerprint. The only thing that can change the pattern is a severe disease."The technology uses the natural reflective and absorptive properties of the retina. When an individual looks at an illuminated green-dot-alignment target, an eye template is acquired from the reflected light. A collimated beam of light from an incandescent bulb or an infrared, low-intensity laser diode or LED passes through the pupil at an angle. The light scans a circular portion in the back of the eyeball. This light is reflected back over the same path as it entered. Only the returning light at 890 nm is captured as data.

This process is similar to taking a picture with a 35-mm camera and a flash, says Cutrer. The red eyes seen in many flash photos are the result of the retina reflecting the intense light. The light used for this system is not that intense, however. It is about as powerful as what you are exposed to when opening a refrigerator door, says Cutrer. The retinal field has 192 identified data points that are used as the basis for creating a 96-byte digital template or "eye signature." The template is stored for future recognition or verification.

The company claims this is the most accurate biometric system on the market today because this is the only biometric product that has never experienced a reported "false accept" at recommended minimum settings. In addition to accuracy, there is a public-acceptance feature that may be higher than with other methods such as fingerprinting. "There are civil-liberty connotations with fingerprinting," says Cutrer.

However, there is reluctance to submit to eye scans as well. "People don`t want to look. They`ve seen the movies. They think it will blind them. But this won`t hurt anyone," says Cutrer. It is just a matter of education.

The EyeDentify system is installed in various US Central Intelligence Agency and Federal Bureau of Investigation buildings nationwide, as well as in national laboratories and at Cape Canaveral (Orlando, FL). A welfare-screening pilot program is underway in southern Illinois. When welfare recipients sign up to collect benefits they are "enrolled." An image is taken of their face with a video camera. All the information is stored in a PC that is linked to a host system. The system communicates in real time over three different counties. "We search for a match on their eye template as they are doing an enrollment. If we find one, we can bring their photo up and see if it is the same person." This helps defeat multiple case identities that are going on in the welfare system.

A newer, faster, and less expensive system will soon be available. "We are experimenting with changing the light frequency," says Cutrer. "Now we can do five different scans; that is, we scan an eye five times and take the best one and store it as a template. Enrollment takes from one to one-and-a-half minutes. Our new system will use instant imaging. An enrollment will take about ten seconds."

The company hopes to have a prototype by the end of the year and a product ready for market by the beginning of 1998. Its goal is to break into the mass market including time and attendance, internet passwords, financial transactions, and auto banking.

Another method of eye biometrics involves scanning the iris. IriScan (Mt. Laurel, NJ) uses the randomly formed patterns in the iris as a "key" (see Fig. 2). Images are captured from 10 to 12 inches away, digitized, and processed into an IrisCode and stored for future recognition. A unique application of this technology is in identifying approximately 10,000 Japanese thoroughbred horses—eliminating the need for painful implants or manual marking. IriScan also is working with Sensar Inc. (Moorestown, NJ) to develop special imaging systems for financial services, in particular for ATMs.Other biometric technologies that are in development include body-odor identification, in which the "scent" of a hand can be digitally recorded, signature verification, wrist-vein recognition, and even keystroke dynamic recognition, or how a person types.

Everyday use

"Five years ago, most people didn`t know what biometrics was," says Mytec`s Clemons. Today, those in the corporate branch of data security, social benefits programs, or public security, such as police or federal investigation agencies, are knowledgeable.

Soon, everyone in a factory environment will also be aware of this technology. Access control was one of biometrics` biggest markets until two or three years ago. Today, the biometric time clock, using this technology for time and attendance purposes, is the key application.

The US government recognized the potential importance of biometrics several years ago and in 1992 formed the Biometric Consortium. This working group comprises representatives from six executive departments of the government and each of the military services. The group serves as the focal point for coordinating and developing advanced biometric processing, testing, and evaluation techniques.

Real-world performance is a prime concern of the consortium. The group warns that the performance claims stated in many sales brochures may not hold true for a given device in a given application. In an attempt to protect consumers, a Biometric Consortium National Evaluation Center was established just this year.

Whether it is the hand, nose, or blink of the eye that will win the hearts and minds of the public is not the question. "There`s a place for every biometric technology that is on the market today, and the true competition is not other biometric technologies but other forms of identification," says Spence. More important than the reliability between systems and body parts is the acceptance from the layperson.

The key to the future of biometrics is public education. "For any biometric product there is an educational process that is necessary to make people feel comfortable with it. It isn`t like a card or key that they can dispose of if they want. This is using a person`s body as some sort of identification," says Cutrer.

Laurie Ann Peach | Assistant Editor, Technology

Laurie Ann Peach was Assistant Editor, Technology at Laser Focus World.