Market Insights: Growing our core photonics businesses: Transcending the $10-million plateau

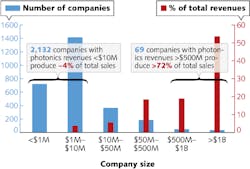

According to research from SPIE, there are about 2750 companies worldwide supplying photonics components and materials, and they employ 700,000 people. These companies sell $156 billion of light sources, optics, and sensors. Of these companies, more than 2000 realize revenues of less than $10 million, accounting for less than 4% of worldwide sales (see figure).

With photonics components at the core of most modern technologies, this is an exciting time for the industry. So, have the stars aligned for more photonics companies to transcend the $10-million plateau? If so, what can a small business do to become a larger market participant?

To explore the question, Linda Smith of CERES Technology Advisors, an M&A advisory firm working with photonics companies, talks with Jan Melles, president of Photonics Investments and founder of 12 photonics companies.

Linda Smith: Were you surprised by any of the research presented by SPIE on the make-up of the core optics and photonics components market?

Jan Melles: Not really—it’s more a confirmation of many years observing the photonics components market. As the SPIE data clearly illustrate, little has changed in the way the components market has developed over many years.

LS: How has the competitive landscape evolved in that time? In industries such as semiconductor manufacturing, as technology matured, the industry consolidated. With photonics components, however, the technologies matured, but much of the industry remains highly fragmented. What do you see?

JM: There are two main reasons why the industry has developed this way. First, there is an absence of a high-volume market such as is the case with semiconductors. Second, the component market does not add enough value to enable component companies to grow into more substantial organizations. To make the jump from being a component supplier to an organization that manufactures and supplies products that add more value has been a difficult one.

LS: Looking at the photonics component companies you invest in, are the biggest challenges they face very different?

JM: In principle, no. If I could wave my magic wand and let those companies blossom where others do not, it would be wonderful but remains a fairy tale. What has improved, however, is the way we deal with this issue more professionally based on long experience. Along the way, plenty of errors were made, but as long as you learn from them, the potential to grow these companies improves.

LS: A small business looking to grow has many options–expand the product line for the current customers, extend into new markets, move up the food chain to compete with current customers. What are the upsides and downsides of these options for a photonics components company?

JM: I think that extending the product line and entering new geographic markets are obvious objectives under any circumstance. However, adding more value by getting into the subassembly or systems business may indeed have serious consequences for the relationship any company may face with its current OEM customer base, assuming there is overlap. This is an age-old dilemma that requires intensive analysis weighing the benefits of more revenue by selling more added-value products versus the risk of losing business.

Over the years, I have tended to be more conservative and in favor of not stepping on our OEM customers’ toes. It takes lot of hard work to gain that kind of business and, at the same time, in most of the companies I have been involved with, OEM sales represented about 50% of total sales. So there really must be strong arguments to risk it—which of course illustrates exactly why it is so tough to go upscale with the value-added principle.

LS: Do you think that the optics industry is too insular? If so, how does this affect careers and the development of talent?

JM: The photonics components industry distinguishes itself from other tech industries through the loyalty to this market by the people working in it. Walk the trade shows like Photonics West or LASER World of Photonics and you will find people who have been in this industry for a long time—more so than in other fields.

This may be a consequence of the fact that on a global scale photonics is a niche industry. Yet there is also a constant influx of young technical talent from the universities who are attracted by the perception that photonics is a clean technology serving a wide variety of technical and scientific applications. So it may be that photonics technology by itself does not attract all the young talent, but using photonics is a pathway to other fields or industries.

LS: Would you say that most small optics businesses struggle to build a global distribution network?

JM: That certainly had been the case earlier on, but these days when most companies have their own websites providing global access, it is not so difficult. Having said that, the Web is no alternative to having a representative organization selling your products in global markets. For those companies already using reps, they should consider setting up their own facilities in key markets if they reach a plateau on sales volume, market share, or both.

LS:Many small optics businesses do not have access to growth capital and are limited to the owners’ personal wealth. Taking on outside investment and/or merging with a larger competitor or partner could alleviate these growing pains. Is this a good option?

JM: This is as much an emotional issue as a rational one. Yes, it would make sense to consider these options, but independence and control over your business is too strong a motive for most small company owners to surrender. Personally, I have been able to overcome those problems by either bank financing or entering into investing partnerships with people I trust to help run and grow the business.

For any of the foreign subsidiaries we established, operations were almost always financed locally or with startup capital coming from the parent company. The managers and key employees of these foreign subsidiaries were given stock in the companies to better align the companies’ interests with their personal interests. Furthermore, when I sold such a company, these managers benefited from the same multiples as I did.

LS: Photonics companies are the key enablers to a wide breadth of vertical markets, from life sciences and manufacturing, to information technology and energy. These vertical markets attract almost 10 times the investment of the photonics companies. I know it is not unusual that profitability and return on investment are more attractive as one moves up the value chain, but is the magnitude of the imbalance unique to the photonics industry? Do you see this trend amplifying?

JM: It is not so much an issue of what application a photonics company is focusing on; it is the value they add to the process. Our discussion here focuses on the photonics components industry, and it is unfortunate that components will only get you so far, which is probably no different from any other industry. I can count the number of photonics components companies that go through the $10-million sales level on the fingers of one hand. One of the usual ways to go “upscale” in a product line is to intensify business connections with OEM customers by supplying them more added-value products, which is beneficial not only for increasing sales, but also for making it more difficult for competitors to compete effectively.

LS: Often guilty of this myself, I find small business owners have a tough time making time to work “on” the business versus to work “in” the business. How did you keep your eye on the big picture, plan with discipline, and stay out of the lab and the coating chamber?

JM: The scene you present is indeed how things often work out in the real world. It is also one of the prime reasons why too many small companies stay small. Most of the time photonics companies are started by an engineer or scientist trying to realize their own company on the basis of technical knowledge from previous studies or work. Where things go wrong is when the founder continues to spend most of their time in the lab and does not pay enough attention to the business aspects of the company.

The founder’s job needs to include two things. First, the founder needs to give employees a clear view of upcoming goals and expectations to meet them. I always presented this in writing to all my employees on a single sheet of paper. And second, they need to realize that without creating an effective team that allows them to delegate operational responsibilities, they will become ineffective and an obstacle in growing the business.

LS: I appreciate having learned best practices from my large corporate employers, but having had to work outside my comfort zone and learn real-time from my mistakes at a family-owned optics business and at startups was invaluable. I learned that as a result of an entrepreneurial culture, individuals behave purposefully and can build more value, more quickly. An entrepreneurial culture can go a long way to compensate for lack of funds, brand, and human resources. How can the entrepreneurial culture that got these small optics companies where they are today help launch them off the $10-million plateau?

JM: It all depends on the aspirations, ambitions, and management skills of the owner. Some owners are perfectly happy to maintain a status quo for a long time, preferring a more comfortable lifestyle but likely not realizing that no company can survive in the long term by sticking to such a philosophy. For those entrepreneurs that have the ambition to grow as much as they can manage, they must realize that no such objective can be achieved without creating an effective team, delegating responsibilities, and inspiring and rewarding the employees.

Linda Smith | President, Ceres Technology Advisors

Linda Smith is a recognized leader in M&A advisory. Spanning the spectrum of photonics-enabled markets, she advised on acquisitions and financings valued at more than $1.5 billion. She founded CERES in 2005 to serve photonics companies underserved by generalist investment bankers. Prior, she held product management, engineering, and sales positions at public and private equity-financed photonics companies.

Jan Melles | President, Photonics Investments

Jan Melles is the president of Photonics Investments and was the co-founder and later chairman of Melles Griot. He is currently on the board of numerous public and private companies, and invests in and brokers the mergers and acquisitions of photonics companies.