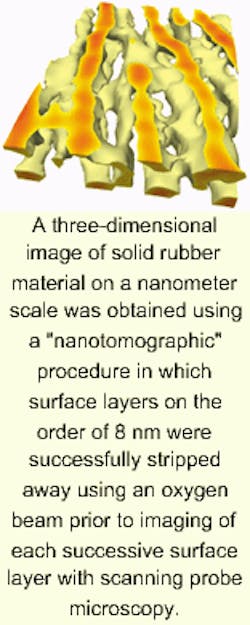

German researchers are developing a method for three-dimensional imaging of very small objects that bears numerous similarities to high-tech medical imaging procedures such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT). Dubbed nanotomography, the method has already achieved record resolution sensitivity in the experimental imaging of synthetic rubber copolymer samples of the poly(styrene-block-butadiene-block-styrene) group.

As with medical tomographic methods, nanotomography produces three-dimensional images through computer reconstruction of data obtained in cross-sectional scans. Unlike CT and MRI, however, nanotomography is invasive. Surface layers are eroded using a beam of oxygen atoms to enable data gathering through subsurface scanning probe microscopy.

Robert Magerle, an investigator at the University of Bayreuth (Bayreuth, Germany) reported that surface layers between 7 and 8 nm in thickness were removed in each of 13 oxygen-beam applications (about 100 nm total) and that a record resolution for volume imaging (10-nm thickness) was obtained using a simple benchtop apparatus.1

In addition to setting a record for fine subsurface resolution, the technique also yielded previously unknown structural information about the specimen. It was already known that polystyrene organized itself into cylindrical domains. But nanotomography revealed a previously unobserved linkage between domains in which one cylindrical polystyrene domain was actually linked to four others (see figure). "This unexpected result demonstrates that real-space volume imaging with SPM offers new information about structures on the nanometer scale, which would be difficult (if not impossible) to obtain with existing techniques," according to Magerle.

Traditional subsurface imaging techniques for small specimens, such as reconstruction from serial sections using transmission electron microscopy and electron tomography, require sectioning the specimen into 10-nm, electron-transparent slices, which poses limitations for curved and rough surfaces and for most nonbiological solid materials.

Secondary ion mass spectroscopy, on the other hand, can handle rough surfaces, but lacks the resolution for detailed observations on the order of nanometers.

"This approach might provide a simple means for nanometer (and even atomic) resolution real-space volume imaging of various materials and physical properties," Magerle wrote. "With the success of SPM in mind, volume imaging by SPM promises new insights into the physics of condensed matter on a nanometer scale."

REFERENCE

- R. Magerle, Phys. Rev. Lett. 85(13) 2749 (Sept. 25, 2000).

Hassaun A. Jones-Bey | Senior Editor and Freelance Writer

Hassaun A. Jones-Bey was a senior editor and then freelance writer for Laser Focus World.