HOLOGRAPHIC OPTICAL ELEMENTS: Printing technology enables HOE volume manufacturing

EVGENI POLIAKOV and LEO KATSENELENSON

Methods for storing and reproducing optical information have greatly boosted interest in holographic products. Indeed, because they are diffractive in nature (with feature size approximately 0.1λ to 10λ, where λ is the recording wavelength), holographic optical elements (HOEs) offer several types of optical functionality. Instead of bending light by curvature and shape, as in the case of typical optical elements such as lenses, HOEs diffract light waves by using a corresponding material profile to make new waves. These HOEs can function like standard lenses, gratings, or mirrors, and they are lightweight and do not require precise surface machining.

Unfortunately, the development of many obvious applications for HOEs, such as three-dimensional (3-D) visualization, 3-D cinema, or 3-D displays, has been hampered for many years. There are two reasons that holography and HOEs have found a limited range of applications that are generally restricted to medicine, museum pictorials, or one-shot visualization objects: cost and complexity. But if you could make a perfect master hologram, a mother of all the others, the master HOE could be replicated numerous times without going through the same development cycle, saving time and reducing costs. Currently, Luminit (Torrance, CA) is using this master hologram methodology to develop custom holographic products; in particular, optical films and diffusers.

HOE science

Optical holography, invented by Dennis Gabor in the 1940s, deals with the recording of scattered optical fields from objects.1, 2 Derived from Greek for "science of writing," holography and the holographic recording process produces holograms or HOEs. These HOEs are typically made by the interference of a reference beam (usually a laser) and an illumination beam (scattered by an object). The resultant two-dimensional (2-D) picture—the hologram—is stored on a photographic film, photoresist material, charge-coupled device (CCD), or is generated numerically.3, 4 The hologram is essentially a collection of interference fringes obtained during exposure of the photosensitive medium to a high-low intensity profile. During playback, the laser light diffracts on the fringes, and the object is reconstructed.

This unique and rather peculiar way of reproducing objects that are no longer there (that is, during playback the laser beam illuminates the interference fringes) is based on retrieval of phase and amplitude information, which uniquely represents the original object. To preserve the phases of the scattered fields, a photosensitive medium is insensitive to the phase and reacts to light intensity. That is what made Dennis Gabor's invention unique: using a second illumination beam along with an object beam allows the beams to interfere so that the interference pattern can be recorded. As long as the interference pattern is preserved, the phase information is preserved and the object can be reconstructed.

Overcoming limitations

Holography has been perceived as an interesting science but a rather complex and nonapplicable technology, especially in terms of high-volume manufacturing. Considering the typical drawbacks associated with using a standard holographic lab such as high material costs, operation in a dark, vibration-free environment, chemical development, materials storage, long recording times, and demanding requirements for uniformity, yield, efficiency, and most importantly, reproducibility, all of these factors can add up to an expensive undertaking.

New technology from Luminit borrows concepts from the printing industry for manufacturing HOE elements with surface microstructure relief patterns applicable to general and backlight illumination, display, automotive, and light-emitting-diode (LED)-based optics. Instead of optimizing an optical recording in an expensive and often futile attempt to produce thousands of identical copies, our HOE development plan is different: make one good master and replicate from it.

Creating the master

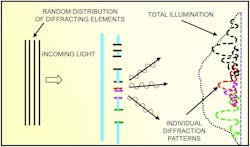

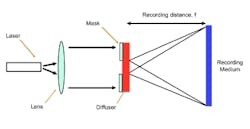

Fabrication of the master HOE begins with an optical setup in which the laser light—which is passed through an optical objective and a shutter—is directed through a mid-mask diffuser made of ground glass (see Fig. 1). The light diffracts on the middle mask and produces secondary (scattered) waves, which are then multiplexed on the surface coated with the photoresist. The individual speckles are engineered on the original master by exposing the photoresist to light variations through the optical setup and a specular pattern—an ensemble of millions of individual photoresist speckles—is obtained.

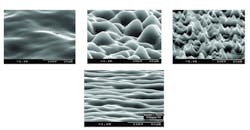

The surface profiles from specular recordings resemble a random collection of lenslets, which are indeed the speckles (see Fig. 2). Feature size varies from 2 to 200 μm, depending on the specified output. Smaller, individual features represent the larger diffraction (and scattering) capability, while the combined microrelief surface of the lenslet ensemble determines the final output. Control of the HOE output (and the individual lenslet shape) is achieved through changing the working distance f, the wavelength, and the middle-mask aperture.5Replicating the master

The absence of structural discontinuities in the HOE master is the key to fast replication manufacturing. Long (1500 ft), wide (more than 48 in.) rolls of film can be replicated in a web process, where an ultraviolet (UV)-grade epoxy is distributed on a substrate and is subsequently hardened by UV light as the seamless metal master rolls over it. By choosing correct web speed and UV dosage, replication from the seamless master is smooth and defects are minimal. The advantages of the web process are clear: fast replication speeds (up to 500 ft/min), large formats (62 in. wide) and great capacity (up to 100 million linear feet of optical-quality films). Essentially a printing process, this method wins over other industrial alternatives in terms of machinery cost (hot embossing), complexity and robustness of the process with respect to custom products (extrusion), or size (injection molding).

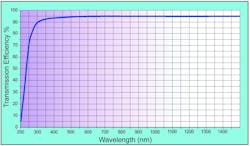

Luminit HOEs are unique because only one beam is used to make them compared to the standard holographical recording process, which uses two beams. Second, the HOEs have randomized surface structures whose optical response (modulation transfer function) is determined by the collection of individual lenslets of varying shapes and sizes rather than by a periodic structure, as in the case of bright-enhancement films produced by 3M (St. Paul, MN). The combination of millions of lenslets determines the output profile and optical properties, leading to very important characteristics such as wide-band operation (300 to 1500 nm) and high transmission (see Fig. 4). Such HOEs effectively act as high-efficiency, wide-bandpass optical filters. They exhibit nearly zero chromatic aberration, atypical for holographic elements that usually demonstrate high diffraction efficiency in a narrow wavelength range.It is important to understand how an HOE obtained at a UV laser exposure (300 nm) does not alter its properties at near-infrared wavelengths (900 nm). The reason is that the HOE surface is represented by a randomized picture of different lenslets. Contributions to the modulation transfer function come from numerous and different spatial frequencies of individual speckles. Therefore, no matter what the wavelength is (essentially, the playback wavelength), there are always features of a particular size within the master that can interact (scatter) the light most efficiently. This is best illustrated by the master grating equation, sineθf = mλ/d + sineθ0, that relates the incoming light angle θ0, the diffractive angle θf, and the surface roughness, d. Different surface roughness features (d), upon playing back (when the light falls on the HOE), contribute to different angles, producing a controlled angular spread (see Fig. 5). This is also the reason for suppressed chromatic aberrations: since there are many values of d, the sensitivity of a particular scattering angle to the wavelength is limited.

HOE performance

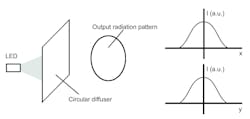

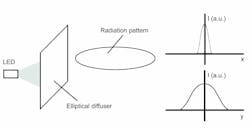

Diffusers from Luminit take the light from a source (coherent or not) and scatter it to a particular design shape. These HOEs are weakly diffractive elements (the light rays do not deviate much from the original path) and therefore obey Fresnel approximations for weakly divergent paraxial rays.6 They are, however, diffractive enough to create a pleasant (to the human eye) Gaussian-type scattering profile with wide roll-offs, or what is known as a standard deviation. This controlled roll-off comes from the fact that these are engineered material surfaces in which the surface roughness, although being randomized, is controlled during the recording process.

Holographic diffusers and directional-turning films with high transmission make exceptional film products for liquid-crystal and rear-projection displays, machine vision, biomedical, aircraft, and automobile applications, and for LED illumination. Functionalities such as spreading light quickly to hide the source and redirecting light toward the viewer benefit the display market. Advantages include the simplification and cost, weight, and size reduction of backlights, while providing equivalents to bright-enhancement (prismatic) films with hybrid integrated options (HOEs with extreme elliptical angle profiles have very similar structure to bright-enhancement films, but are less expensive). With further commercialization of these HOEs and the applicability of the printing-based manufacturing process to markets such as the rapidly evolving solar-cell industry, the future will likely see further proliferation of this technology and many more HOEs in production.

REFERENCES

1. D. Gabor, Nature 161, 777 (1948).

2. D. Gabor, Proc. Royal Society 197, 454 (1949).

3. http://www.hololight.net/

4. J.P.Walters, J. Optical Society of America A 58, 368 (1968).

5. J. Peterson and J. Lerner, "Homogenizer formed using coherent light and a holographic diffuser," U.S. patent 5,534,386 (1996).

6. M. Born and E. Wolf, Principles of Optics, 5th ed., Pergamon, New York (1975).

Evgeni Poliakov is senior optical engineer and Leo Katsenelenson is vice president of engineering at Luminit, 20600 Gramercy Place, Suite 203, Torrance, CA 90501-1821; e-mail: [email protected]; www.luminitco.com.