Medical Lasers/Neuroscience: Photobiomodulation and the brain: Traumatic brain injury and beyond

Traditionally referred to as low-level light therapy (LLLT) and various other names (see sidebar, "Call it photobiomodulation"), photobiomodulation (PBM) therapy uses low-power monochromatic (or quasimonochromatic) light1 typically ranging from visible blue to near-infrared (NIR; approximately 400–1500 nm) to stimulate or inhibit cellular processes. In a new literature "mini-review," researchers report that science has achieved a "quantum leap" in the understanding and use of light to restore physiologic function, arguing that PBM therapy "represents a novel hope" for treating complex diseases.2 With its cost-effectiveness and potential to benefit the lives of the most vulnerable people, the researchers forecast the mainstreaming of PBM.

The list of applications for PBM, ranging from pain relief and wound healing to heart attack reduction, is astonishing. One such application, the treatment of brain disorders, is particularly compelling because drug treatments for neurological and psychiatric diseases have been largely ineffective.

In a keynote talk called "Photobiomodulation in traumatic brain injury (TBI): Can PBM help the brain to repair itself?" at SPIE Photonics West 2016's Biomedical Optics Symposium (BiOS), Michael R. Hamblin, Ph.D., explained the development of PBM, its operation, and its application to (among other things) treatment of traumatic brain injury, cognitive enhancement, and psychiatric disease. Those who follow PBM need no introduction to Hamblin: He is a principal investigator at the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, associate professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, and a member of the affiliated faculty of Harvard-MIT Division of Health Science and Technology.

The mechanics and operation of PBM

Work by Hamblin and his collaborators has helped elucidate the mechanics of PBM, as they have sought to understand the impact of light at the molecular, cellular, and tissue levels. His team has prioritized this work to help the technique gain acceptance among not only the medical community, but also the public. They report that the large number of parameters involved in PBM—including wavelength, fluence (energy received by target surface per unit area), dosage, treatment timing, and repetition—have resulted in the unfortunate publication of PBM studies with negative outcomes owing to flaws in experimental designs.3

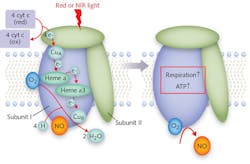

To this end, Hamblin's lab pursued a number of in vitro experiments. They have shown that the response to light happens within a cell's mitochondria.3 They have also confirmed the theory that cytochrome c oxidase (CCO, a.k.a. Complex IV) is the specific structure within the mitochondria that serves as a photoacceptor and thus is responsible for PBM effects (see Fig. 1).3,4 Further, the researchers enabled an understanding of what action results from CCO's absorption of light energy: PBM prevents the inhibition of respiration (and subsequent decrease in energy storage) in a stressed cell by dissociating nitric oxide (NO) and reversing the displacement of oxygen from CCO. This triggers transcription factors that can alter gene expression levels.

One in vitro study documented five separate, fundamental responses of primary cortical mouse neurons to 810 nm illumination.8 This work also documented light's biphasic dose response, demonstrating that small doses of light stimulate cells, moderate doses inhibit cells, and large doses can kill cells. In live mice, the researchers found that while laser light at 665 and 810 nm was able to significantly boost neurobehavioral performance after severe TBI, 980 nm light was not.5 They also compared continuous-wave (CW) vs. pulsed modes of 810 nm laser light, and discovered that the therapeutic effect for TBI was more effective at 10 Hz pulse frequency than at CW and 100 Hz.6

TBI and transcranial PBM

Traumatic brain injury is a problem affecting military personnel and civilians alike. In the U.S. military, there were 43,799 new cases from 2003 and 2007, and approximately 28% of patients at Walter Reed Army Hospital have TBI. According to the Centers for Disease Control, total combined rates for per-capita TBI-related emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths grew 58% from 2001 to 2010. A significant percentage of those affected die, and even more are permanently disabled.

But, as Hamblin and his collaborator Margaret Naeser of Boston VA Hospital report in a review article, even those suffering mild TBI (mTBI) are at risk for long-term effects, which compound with successive injuries.7 And those who incur mTBI in military service commonly suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well. TBI also heightens risk of sleep disturbances, and increases inflammation of the brain, which is suspected of leading to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's. Furthermore, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which affects other athletes who suffer repeated concussions, has recently been identified as a progressive degenerative disease. No drug treatments exist for the secondary injuries that follow mTBI, or for prevention of the associated cognitive and behavioral problems—and psychological treatments are hindered by the brain damage.

NIR light at 800–900 nm can penetrate through the scalp and skull about 1 cm.7 NIR transcranial LED (tLED) has been shown to provide anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. It also can increase heat-shock protein, which prevents the misfolding and unwanted aggregation of proteins. And tantalizingly, Hamblin's lab has also shown in animal studies the potential for increased neurogenesis and synaptogenesis.

The collaborators note that clinical studies show that serial tLED treatments help those suffering from chronic TBI improve in terms of cognition, PTSD symptoms, and sleep. In one study, for example, patients with chronic TBI, who began PBM therapy at 10 months to 8 years after their brain injuries, reported significant improvement after a regimen of 18 red/NIR tLED treatments at 500 mW with 22.2 mW/cm2 and 22.48 cm2 per treatment area. Improvements were reported in both executive functioning and verbal memory, along with improved sleep-and in patients with PTSD, fewer PTSD symptoms were experienced.

The impact on people's lives can be dramatic. A report of two case studies explains the results for two women in their 50s.9 One realized a 10x ability to do computer work after eight weekly treatments—seven years after the motor vehicle accident that left her impaired. She subsequently began using a home unit daily to maintain the effects. The other, who had sustained multiple concussions and PTSD, received daily treatment with a home unit and was able to come off medical disability status after four months of home treatments. Subsequently, she returned to full-time work.New research, more applications

New studies involving transcranial PBM include three by the Boston VA Hospital team address ongoing effects of TBI among veterans:

- Noninvasive LED Treatment to Improve Cognition and Promote Recovery in Blast TBI (principal investigator: Bogdanova);

- LED Light Therapy to Improve Cognitive/Psychosocial Function in TBI-PTSD Veterans (PI: Jeffrey Knight); and

- Transcranial, Light-emitting Diode (LED) Therapy to Improve Cognition in Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses (PI: Margaret Naeser).

As Dr. Naeser explains, the latter study involves not only an LED helmet by Photomedex (Horsham, PA), but also light applied through the nasal passages and ears: VieLight Inc. (Toronto, ON, Canada) developed intranasal diodes, and MedX Health (Mississauga, ON, Canada) supplied LED cluster heads for the ears (see Fig. 2). This work will compare results with real and sham devices, which look identical. Goggles, worn by both the researchers and research participants, block out (or lend the appearance of blocking out) the red light used in one of the intranasal diodes (all other devices use NIR light). Hamblin noted that similar improvement has been demonstrated in stroke patients, and he described other studies exploring the use of light for treating major depressive and anxiety disorders, primary progressive aphasia, Parkinson's disease, and Alzheimer's disease. In fact, VieLight founder and CEO Lew Lim reports "promising results" from new clinical trials on participants with Alzheimer's. We look forward to reporting more.

Russian PBM specialist Tiina Karu, Ph.D., Sc.D., asks whether it is time to consider PBM therapy as a potential drug equivalent.4 It is a good question.

REFERENCES

1. J. J. Anders, R. J. Lanzafame, and P. R. Arany, Photomed. Laser Surg., 33, 4, 183–184 (Apr. 2015).

2. L. Santana-Blank, E. Rodríguez-Santana, K. E. Santana-Rodríguez, and H. Reyes, Photomed. Laser Surg., 34, 3, 93–101 (Mar. 1, 2016); doi:10.1089/pho.2015.4015.

3. J. T. Hashmi et al., PM & R, 2 (12 Suppl. 2), S292–S305 (Dec. 2010); doi:10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.10.013.

4. T. Karu, Photomed. Laser Surg., 31, 5, 189–191 (2013); doi:10.1089/pho.2013.3510.

5. T. Ando et al., PLoS ONE, 6, 10, e26212 (2011); doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026212.

6. Q. Wu et al., "Low level laser therapy for traumatic brain injury," Proc. SPIE, 7552, 755206-1 (2010); doi:10.1117/2.1200906.1669.

7. M. A. Naeser and M. R. Hamblin, Photomed. Laser Surg., 33, 9, 1–4 (2015); doi:10.1089/pho.2015.3986.

8. S. Sharma et al., Lasers Surg. Med., 43, 8, 851–859 (2011); doi:10.1002/lsm.21100.

9. M. A. Naeser, A. Saltmarche , M. H. Krengela, M. R. Hamblin, and J. A. Knight, Proc. SPIE, 7552, 75520L-12 (2010); doi:10.1117/12.842510.

Call it photobiomodulation

As of 2016, the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) Browser on the U.S. National Library of Medicine site—the Library of Medicine's list of terms used to index articles in biomedical journals worldwide—began listing photobiomodulation (PBM) therapy as an indexing term. The development is important because it enables clear differentiation between the use of light-based devices for thermal effect and PBM1—the use of light to trigger nonthermal, non-harmful biological reactions that result in beneficial therapeutic outcomes. These reactions, Michael R. Hamblin explained, can be the stimulation (as with neurogenesis) or inhibition (for instance, the transmission of pain signals along nerve fibers) of cellular processes.

What's wrong with the term low-level light therapy (LLLT)? For one thing, the acronym has often been taken to stand for low-level laser therapy, and the word laser is not appropriate because, while the techniques originated in the 1960s, these days, LEDs are often used instead. Moreover, Hamblin pointed out, it has never been clear exactly what is meant by "low."

About the Author

Barbara Gefvert

Editor-in-Chief, BioOptics World (2008-2020)

Barbara G. Gefvert has been a science and technology editor and writer since 1987, and served as editor in chief on multiple publications, including Sensors magazine for nearly a decade.