Three market leaders reorganize to become successful industry suppliers

Successful products in the industrial manufacturing market are different from those that succeed in the scientific and research markets. The industrially appropriate products are more durable and more reliable; they generally are designed to meet the precise needs of a specific application. Companies that are successful in providing industrial products are also different from what they were when they were scientific suppliers. Here are three companies, each successful in their own markets, that have made and continue to make the transition from scientific/ research-based company to industrial supplier.

General Scanning

In 1988, when Charles Winston became president of General Scanning Inc. (GSI; Watertown, MA), the company, a manufacturer of beam-steering motors, faced a choice: either continue to be a components supplier, by developing and acquiring more components, or "move up the food chain," by vertically integrating, providing subsystems and complete systems. The company moved toward vertical integration, driven by three major changes taking place in manufacturing—the push to shorten product-development cycles, the move toward just-in-time vendor deliveries, and the trend toward outsourcing of noncore technologies. Each of these tendencies moved manufacturing companies away from developing their own manufacturing tools and toward partnering with tool manufacturers to get more standardized manufacturing, assembly, and test systems.

GSI created a presence in the systems business by developing a joint venture with Teradyne (Boston, MA) called TLSI. The systems capability for the business and an installed base of equipment came from Teradyne. GSI put together the management structure and began to develop distribution channels and a customer base. The beginning was very rocky, especially because the semiconductor-equipment market was at its nadir and stayed down for longer than predicted. Cost control and cash-flow management were key elements in the management of the joint venture until the market permitted growth to occur.

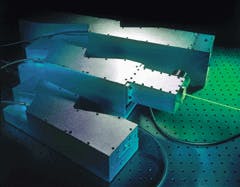

Meanwhile, General Scanning was implementing several other changes necessary to reorient the entire company. The company was reorganized into divisions to focus on respective markets, customers, and products. Complete systems were developed to support specific scanning-based applications (see Fig. 1). The Optical Scanning Products division continued to support the component products.

The sales force was restructured into separate sales groups for each division, because it was believed that a systems sale is essentially different from a component sale: not only different price points but different buying motives. Additionally, confidentiality and "arm’s length" transactions had to occur, because some components might be sold to competitors of the complete systems that GSI also sold.

Service and customer support make up another aspect of the complete product and service solution that GSI needed to provide. Service at the component level is different from the support that a semiconductor fab requires for laser trimmers or marking systems that must be productive in a "7 by 24" environment. The change in the nature of service and support went together with a cultural change within GSI, emphasizing satisfying customer needs, not only with technology but with a complete solution.

Much of these changes occurred eight to ten years ago. When asked when the process was completed, Winston replied, "The job of becoming a systems company is never done. GSI is a participant in the infinite series of improvements and changes necessary for an on-going business."

GSI is now incorporating more software into its products, providing increased levels of control and automation. The company is continuing to re-evaluate businesses to better satisfy the needs of its customers. It has just reconfigured its sales force, so that customers that purchase several different types of products from GSI will only interface with one salesperson, who will manage the entire account.

Spectra-Physics Lasers

Spectra-Physics Lasers (SPL; Mountain View, CA) had a scientific-market focus in 1990, when approximately 90% of its revenue came from laser sales to universities and research facilities. The forecasted growth was no longer in scientific applications, however, but in the industrial sector. Spectra-Physics Lasers, under its new president Pat Edsell, set about the process of refocusing its business toward the industrial segment, with some urgency, because the company was not profitable at that time.

The first step was to reorganize the company, creating an OEM business unit with a market/applications focus. The goal of that unit was to develop and manufacture products that met the specific needs of key large accounts (see Fig. 2).The second step was to find a way to participate in the technological shift from gas to semiconductor solid-state lasers. Because SPL did not have a captive diode-laser source, the company acquired Opto Power Corp. (Tucson, AZ) in 1992.

The third step was to change the culture within the organization, from one accustomed to a university environment to one that understands the needs and demands of industrial customers. Instead of creating products that were at the leading edge of technology, products were designed with an emphasis on reliability and manufacturability that met the specific requirements of that application. Changing the culture resulted in employee turnover, as some people were either unwilling or unable to accommodate the new direction. The company experienced a significant decrease in size, as it responded to soft markets and the need for cost containment.

Spectra-Physics Lasers also created an OEM account-management organization to complement the existing sales force. Each member of the field sales force had a geographic territory. Within the territory, each salesperson was responsible for scientific and research sales as well as for prospecting for OEM and industrial business. Once the industrial account reached a certain threshold, it was assigned to an OEM account manager.

The account-management group is organized by application, not geography. SPL is pursuing applications in four distinct areas: material processing, medical, printing or reprographic processes, and the scientific market.

When asked where in the transformation process SPL was, Pat Edsell replied, "The company’s revenue mix has shifted so that this year approximately 60% of our revenues will come from OEM and industrial applications. I expect that shift to continue, eventually reflecting the overall market in which high-power diode-laser applications dominate." He further indicated that most of the growth will come from developing opportunities from within the organization, rather than by acquisition.

Newport Corp.

Newport Corp. (Irvine, CA) began its transformation more recently than the other two companies. In 1993, more than two-thirds of Newport’s business came from sales to research-and-development facilities, including universities. Catalog sales were a primary revenue source, supplemented by the efforts of a geographically based sales force. The 1994 catalog includes some of the initial products that Newport targeted at the industrial markets, including assembly tools. The acceleration of the Newport transformation began two years later, in 1996.

Newport came to the same conclusions from the market data as had Spectra-Physics Lasers; growth was in industrial applications, not R&D markets. Newport looked at its own broad product offerings and categorized its core competencies in five key areas: semiconductors, computer peripherals, fiberoptic telecommunications, science/R&D, and other metrology applications (see Fig. 3). These areas make up the markets upon which Newport would focus.Having breadth of products is not sufficient if there are gaps in being able to provide a complete technical solution. The company closed some of those gaps through acquisition, others through internal development efforts. For example, many subsystems and most complete test and inspection systems require some aspect of machine vision. Newport acquired RAM Optical Instrumentation Inc. (Irvine, CA), in part to provide that system capability internally.

Many of the company’s core platforms required re-engineering to meet the needs of the industrial market. Similarly to GSI, Newport’s customers had been buying a kit of components, assembling the pieces themselves, and then becoming upset at incompatibilities and their inability to integrate the components into a workable subsystem. The company saw its ability to add value by providing the systems integration, emphasizing front-end engineering for reliability and performance.

A culture change is in process within Newport, as well. The organization must change its ways of doing business by becoming a reliable, just-in-time vendor. Performance measures have been instituted, not only for product performance, but also for customer service, including response times for inquiries.

Results from these efforts of the past few years are already evident. The revenue mix has moved to two-thirds industrial, one-third R&D, with the shift toward the industrial markets not yet complete. According to Robert Deuster, chairman, president, and CEO of Newport, "We are continuing to create a balanced portfolio of applications, centered on our core competencies, that not only provides a quality solution for our customers but also provides an attractive double-digit growth rate for our investors." Deuster also indicated that Newport’s transition to a top-level industrial supplier was still in process. The company will continue to round out the portfolio of products and services that it offers its customers, with both development and acquisition.

The process of changing the direction of a corporation, the nature of the products and services that it offers, and the employee environment are significantly influenced by the direction set by top management. The process is often difficult and even painful. The rewards, as illustrated by the three companies discussed here, are not only better product and greater market share, but also long-term corporate viability, a satisfactory return to the investment community, and satisfied customers.