Ophthalmology/Femtosecond Lasers: Clarity on the laser cataract conundrum

Long before the femtosecond laser gained FDA approval for cataract surgery in 2010, the technology was greatly anticipated for its ability to improve ophthalmology's most common surgical procedure. But recently, ophthalmologists have begun debating its value.

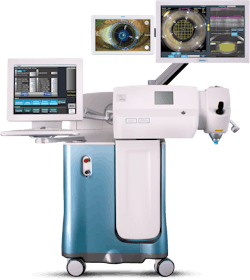

It's a little startling to hear Richard L. Lindstrom, MD, an avid proponent of femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery (FLACS) when I interviewed him just five years ago, report that the nine cataract surgeons at his practice, Minnesota Eye Consultants (Bloomington, MN), stopped pursuing FLACS after using both the LenSx (Alcon; see Fig. 1) and LensAR (LensAR) systems for two years. "We evaluated our outcomes and could not find any measurable benefit," he explained. "We decided that if our patients were going to pay a premium for something, we wanted it to be something that added value like an astigmatism or presbyopia-correcting IOL." (The procedure is not covered by insurance, so as with procedures such as LASIK, it is provided as a premium service to customers at $1500–3000 per eye.)

And this view is fairly widespread: 43% of those responding to a 2016 survey published by the American Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery (ASCRS) doubted the clinical benefit of FLACS. In any case, Lindstrom and his colleagues are now investigating "cheaper and better alternatives with the same potential benefits" in the form of handheld mechanical tools such as Zepto (Mynosys) and miLoop (IanTech, a company Lindstrom serves as a member of the board of directors; see Fig. 2).Wait a second. A manual tool with the same potential as a sophisticated, automated system? What's going on here?

With and without lasers

Modern cataract surgery creates corneal incisions and opens the eye's lens capsule (in a procedure called capsulorhexis) to allow phacoemulsification ("phaco" for short), a process whereby an ultrasonic device is inserted to break apart the clouded natural lens, and the fragmented cataract is suctioned out. The surgeon then inserts an artificial intraocular lens (IOL) so that the patient need not rely on thick glasses for the rest of his or her life.

Without laser assistance, the procedure involves the use of surgical blades and other handheld tools—not to mention considerable skill and steady hands. Near-infrared laser systems—the latest of which truly are robots capable of perfect reproducibility—penetrate the anterior segment of the eye and, guided by imaging systems, precisely outline the anatomy, cut incisions in the cornea, and perform capsulorhexis and phaco procedures.1 But improving on the skill and speed that top surgeons like Lindstrom have developed over decades of practice is a bar that even the most sophisticated systems are hard-pressed to meet.

"As surgeons, we do our best work for patients when we embrace technologies that overcome our own limitations..." says John A. Hovanesian, MD, FACS.2 But surgeons like Lindstrom who have few, if any, limitations relative to cataract surgery were the early adopters of FLACS.

Add to this "no room for improvement" scenario the fact that the price of a FLACS system (roughly $500,000) keeps it beyond the reach of newer and less-skilled practitioners (59% of respondents to the ASCRS survey considered FLACS technology too costly), and the fog begins to clear. Especially when a couple of large research studies (studies that many contend were poorly designed, and therefore generated skewed results) support the "no measurable benefit" conclusion.

In other words, the very practitioners most likely to benefit from FLACS are those least likely to have tried it-and are hearing from leaders in the field that it's not worthwhile. Eric Donnenfeld, MD, Clinical Professor of Ophthalmology, New York University Medical Center, said a year ago that while FLACS may not provide an advantage for the most skilled surgeons, it can definitely enhance outcomes for average surgeons, and will ultimately allow more doctors to do a good job of performing refractive cataract surgery.3 Today, he stands by that comment "more than ever."

The way out

So, how do we get out of this mess? With smaller, lower-cost instruments that provide greater efficiency than most of today's options, says Rosa Braga-Mele, MD, MEd, FRCSC, Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Toronto (Canada)—who, by the way, concedes that the technology is here to stay.

Instrumentation developers are listening, and although some were not able to go on record with their comments, these priorities seem to align with their plans. In the competitive market that is FLACS, Hadi Srass, Project Head III, Surgical Instrumentation, R&D at Alcon LenSx—the largest supplier of FLACS systems—was unable to describe specific goals. But he did state that Alcon maintains close relationships with users and that the company's development team is targeting issues important to surgeons. He also explained that Alcon considers a few things—including phaco—core to the company, and as a leading provider of FLACS systems, is prioritizing femtosecond technology as well. He also noted that advancement in technology is to be expected, especially for an application just a few years old. "The answer is not to get out of the technology, but to take it to the next level," Srass said, who spoke of "raising the bar" to enable advanced capsulotomy and lens fragmentation, and better corneal incisions.

Developments to meet growing needs

You can get a glimpse of where developments are headed by looking at Ziemer Ophthalmology's (Port, Switzerland) LDV Z8 instrument, which is smaller than its competitors (see Fig. 3) and mobile—characteristics that address two of Braga-Mele's three criteria. It turns out that FLACS systems, which tend toward bulk, were not originally designed for use in sterile operating rooms and, as a result, patients must be moved from room to room to complete their procedures. This, of course, lowers efficiency and raises risk. Braga-Mele expects significant change in "the next 2–5 years."Frank Goes, MD, extrapolates on current statistics to predict that in just five years, the world's aging population will need treatment for 50 million cataracts annually, requiring 125,000 surgeons—and double that a decade from now.4 "Faced with such numbers, robots and technicians will have to take over," Goes wrote. "Cataract surgery only recently became more automated, the femtosecond laser having taken over part of the job since 2013. Femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery will continue to grow in popularity and the recently introduced nanolaser photo-fragmentation takes over another significant part of the surgery."

FLACS instrumentation designers are well aware of the opportunity posed by an aging population, and are focused on their ability to solve problems and address needs. The news that they'll be sharing in the coming months and years will further clarify the technology's role in this fast-growing segment.

REFERENCES

1. J. L. Alió, Saudi J. Ophthalmol., 3, 219–223 (2015).

2. J. A. Hovanesian, "How robots will replace us as eye surgeons," Healio Medblog (Aug. 2, 2017); see https://goo.gl/Sy7C5C.

3. V. Caceres, "FLACS: Friend or foe to refractive cataract surgeons," Ophthalmology News (2016); see https://goo.gl/HEfwSV.

4. F. Goes, "The future of cataract surgery," Ophthalmology Times (2017); see https://goo.gl/RXt4bd.

Barbara Gefvert | Editor-in-Chief, BioOptics World (2008-2020)

Barbara G. Gefvert has been a science and technology editor and writer since 1987, and served as editor in chief on multiple publications, including Sensors magazine for nearly a decade.